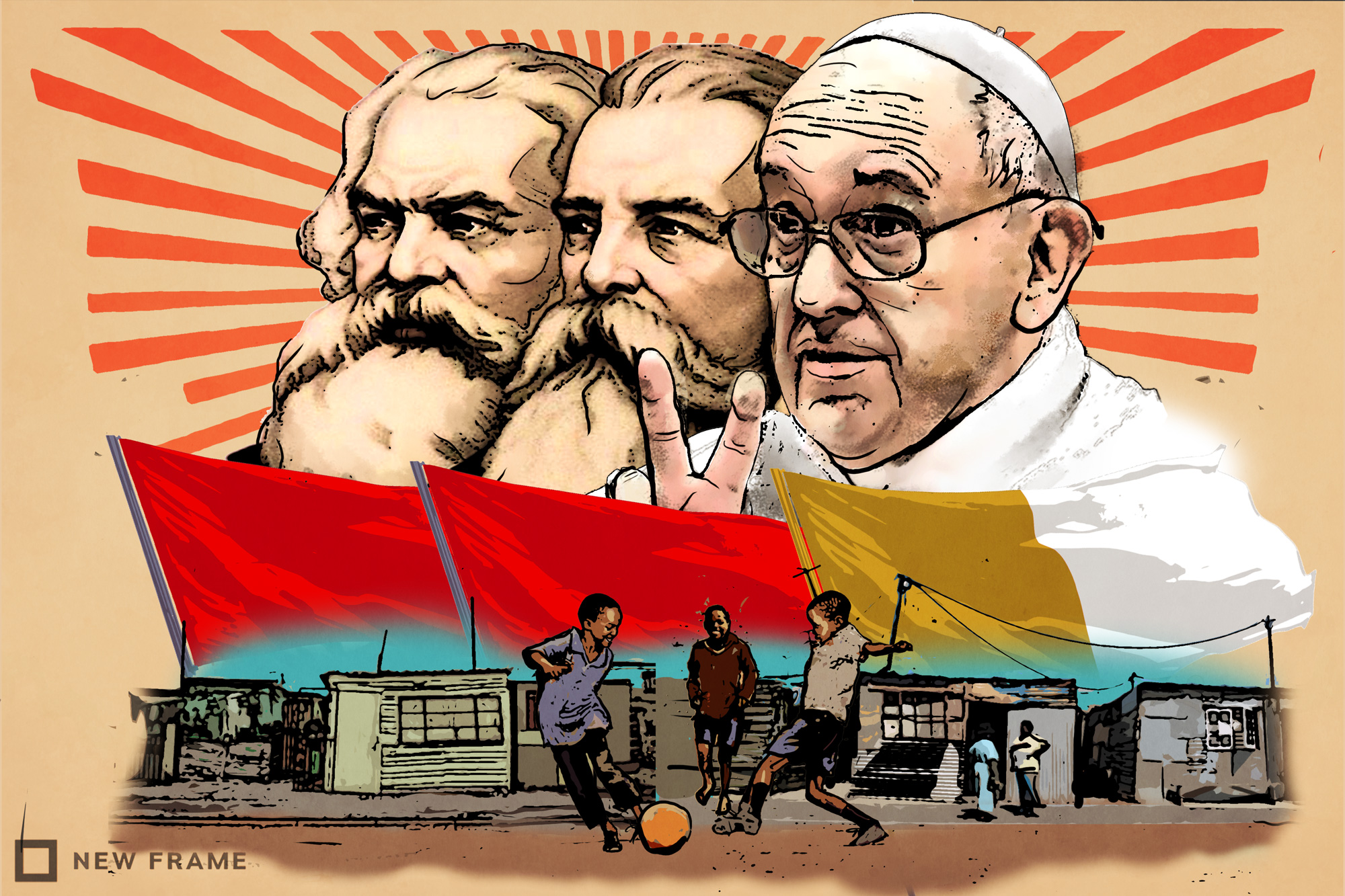

Text Messages | When Christ met Marx

In the 1970s, Christianity took up the mantle of Marxism and tried to steer the Catholic Church to practise liberation theology. Now, another pope hopes to revive these ‘vanished trees’.

Author:

12 September 2019

For the briefest of times in the 1970s, Catholicism and Marxism were almost in step with each other. South American theologians and a number of cardinals, bishops and clergy there had developed, preached and were attempting to put into practice something called liberation theology.

This revolutionary approach sought to make social justice and achieving it central to Catholic practice on the continent. And it tried to do so at a historically unpromising time for such an idea. South and Central America were in the main ruled by military regimes, dictators and despots; everywhere, democracy and the rights of workers and the poor were in retreat.

For a glorious passage – longer than the metaphorical revolutionary spring but shorter than the decade in which it flourished – liberation theology looked as if it might have a liberating effect on the politics and the possibilities of the region. It seemed even that it might exert an influence on the broader body of the Roman Catholic Church and move it towards pastoral intervention in the cause of poverty and inequality.

When Albino Luciani was elected pope on 26 August 1978, taking the name John Paul I, it seemed a promising moment for liberation theology to take off. The smiling pope won the hearts of millions around the world, not only Catholics and Christians. Relaxed, unassuming, shedding Vatican pomp and ceremony, John Paul I was in essence Pope Francis 35 years before the advent of Francis.

Murder in the Vatican?

It is no exaggeration to say that this Roman Spring suggested a worldwide thawing in Catholic practice. But, only 33 days after his election, John Paul I died, apparently of a heart attack. The rapidity of his burial, together with other speculation around his death – he had, for instance, ordered an investigation into the Vatican Bank – led to conspiracy and other theories. The English writer David Yallop even published a book, In God’s Name: An Investigation into the Murder of Pope John Paul I.

What followed was the election of the anti-communist Karol Wojtyla, who assumed the name John Paul II. His experiences of dealing with a repressive communist regime in Poland set John Paul II against any whiff of what might be socialist ideas by stealth, which is what he and the conservative cardinals and Vatican bureaucracy thought of liberation theology.

In a brutal culling campaign, John Paul II rid the Church of progressive theologians, cardinals, archbishops, bishops and priests, especially in Latin and South America. Liberation theology disappeared as a workable dynamic within the church, its proponents muzzled, sidelined, rusticated.

Fast-forward not quite 35 years to March 2013 and the election of the first Latin American pope, Jorge Bergoglio, Pope Francis. Born in Argentina to migrant Italian parents, he became the archbishop of Buenos Aires and was respected for his emphasis on the pastoral rather than the doctrinal.

Bergoglio was committed to serving the oppressed, the poor and the working class, in whose midst he lived, shunning the archbishop’s traditional residence. Among his most constant calls was one for social inclusion and care for those on the margins of society. This is something he has made a regular theme as pope, travelling to and urging governments, clergy and laity to focus on what he calls “the peripheries”.

An unbridgeable gap

In the second week of September 2019, Francis visited Mauritius, Madagascar and Mozambique, his fourth visit to Africa. In Mauritius, he pleaded the cause of migrants, one of the defining issues of his papacy, saying, “I encourage you to take up the challenge of welcoming and protecting those migrants who today come looking for work and, for many of them, better conditions of life.”

It feels like the 1970s again, another moment freighted with possibility. This is not to suggest a resurgence of liberation theology, whose proponents are dead, aged and vastly diminished in number. But it is to think of something more radical: an opportunity to reflect that Marxism and Catholicism are social justice movements with much in common apart from the small issue of god/God.

The gap between the two is unbridgeable, of course. How could a body of thought that deems religion “the opium of the masses” possibly countenance any sort of rapprochement? And how could a religious institution consider reaching out to an ideology that it regards as the devil’s own work?

And yet Catholicism and communism have at heart the welfare of those pushed to and kept at the brink of existence, those dwellers forever on the margins who are denied the fulfilment of any centre-seeking impulses that they might wish to indulge. Too far apart in most other aspects, Christ and Marx cannot be even strange bedfellows. Instead, Catholicism and Marxism are like the “vanished trees” in F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, that “had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder”.