The apartheid wars: freedom for perpetrators

Despite the TRC’s recommendations, why have none of the powerful men responsible for apartheid’s atrocities, including the Sharpeville and Kassinga massacres, been prosecuted?

Author:

21 April 2020

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was a means to save South Africa from unending civil war. Amnesty in exchange for full disclosure of political crimes was the price for peace. But the TRC was a very costly expedient in human and political terms. Not only regarding justice for victims, but also concerning the non-apprehension of perpetrators of torture and killings, and the eventual suppression of prosecutions. No reckoning with the past was achieved.

After 1976, apartheid was recognised as a crime against humanity, but the architects of apartheid and their senior generals negotiated themselves out of murder. The ANC elite, responsible for the harsh treatment of thousands of the “Soweto generation” in its camps in Angola promoted this cover up. Jacob Zuma, an ANC espionage chief in the 1980s and future state president, was “chief among them”: according to Lukhanyo and Abigail Calata, his eyes “firmly fixed on self-interest and [power]”.

On 5 February 2019, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and 10 other “deeply outraged” former TRC commissioners wrote to President Cyril Ramaphosa demanding an official commission of inquiry to investigate “political interference” in suppressing prosecutions recommended by the TRC. In April, Lukhanyo Calata informed the Zondo Commission of 300 cases referred for prosecution that “were all deliberately suppressed, and the perpetrators shielded from justice”.

The Sharpeville massacre

The Sharpeville massacre, beginning on 21 March 1960, launched the apartheid wars. It was a watershed, nationally and internationally, with huge ramifications. The Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) had been formed the previous year under Robert Sobukwe. They organised a march of some 300 people protesting against pass laws. Sobukwe stressed their “absolutely non-violent” intents: “We are ready to die for our cause but we are not ready to kill.” Nonetheless, the police opened fire, killing 69 marchers. Conflict erupted in Langa in Cape Town simultaneously, killing two more and injuring 50, and more in coming days in other cities. Sharpeville “signalled an end to the era of non-violent struggle, and ushered in a period of armed struggle”.

Steve Biko and black consciousness

Born in 1946, Biko was educated at Lovedale and St Francis Colleges, before entering the University of Natal Medical School. He was soon elected to the Students’ Representative Council (SRC), and involved with the multiracial National Union of Students (Nusas). Until the late 1960s, black students saw it as their only agency for change. But Biko’s direct experience showed him that Nusas offered only “a one-way course with the whites doing all the talking and the blacks listening”.

In 1968, he and his confederates formed the South African Students Organisation (Saso). The new organisation and its ideology “struck a hugely responsive chord in young blacks, and the movement spread rapidly”. Like no other ideology, it “inspired hope and gave direction and purpose to black lives”. In 1969, the Black People’s Convention (BPC) was launched as a coordinating body in fields like community health and education.

Along with a belief in the importance of developing a new way of life, was anti-elitist democracy. “Our belief was essentially … that we must not create a leadership cult.” Biko firmly upheld this principle. He was president of Saso for only one year, and virtually all the first presidents of Saso served only one year. Opposition to the “leadership cult” was critical for democratisation and “focused attention on the message rather than the messenger, on the core of what you are saying, not individuals”.

Related article:

Early on 7 September 1977, Biko was confronted by a group of security police bent on murder. He died on 12 September 1977, but was effectively dead just minutes after the confrontation began. The police began their assault just after 7am. As Peter Bruce pictures it: “One of them would have hit him. He would have hit back.” The multiple interrogators would “then have assaulted him with brute force”.

An amnesty hearing in 1999 heard that Harold Snyman led the interrogation, while Jacobus Beneke, Daniel Siebert and Rubin Mark all joined in bashing and shackling Biko: typical of what occurred: Beneke “ran in and shouldered Biko roughly below the ribs towards the wall”. After he sustained the fatal injury, he was “shackled to a metal grille and transported [naked in an open vehicle] from Port Elizabeth to Pretoria”.

The Soweto uprising and democratisation

The Soweto uprising began in May 1976, initially as a protest against the use of Afrikaans in secondary schools. A class boycott began at Orlando West Junior Secondary school, and by month’s end the number of boycotting schools had risen to six. Education authorities declared that they would expel pupils and transfer teachers, but more schools joined the boycott.

The state’s resort to force was quick. Captain “Rooi Rus” Swanepoel led the riot unit into Soweto and Alexandra around 16 June, with a shoot-to-kill policy. Such action was strongly promoted by Prime Minister John Vorster in parliament on 18 June: “The government will not be intimidated. Orders have been given to maintain order at all costs.”

Related article:

The government closed schools in at least 80 townships country-wide. In August, as the police conducted a series of raids on schools, searching for Soweto Student Representative Council (SSRC) leaders, the uprising assumed its full character as an organised movement for participatory democracy.

Certain schools and students became prominent. The Morris Isaacson School in Soweto played “a leading role in raising awareness and organising among students. It produced some of the organisers of the 16 June protest”, including Murphy Morobe and Tsietsi Mashinini. The TRC noted “the unusually close relationship between students and teachers”, and the “overtly anti-establishment stance of the principal, Lekgau Mathabathe”.

The June protest was planned by an Action Committee, an elected body of secondary students in Soweto. They were imbued with a strong sense of mission. A member of the committee, Dan Motsisi, said that “students felt they were taking up a battle their parents and teachers had lost”. Ellen Khuzwayo noted the powerlessness of their elders: “75% of the parents of these children had no education” and were readily intimidated by the police. “These kids took it into their hands,” she said.

To preserve secrecy, “the Action Committee gave itself only three days to organise the march”. Morobe was aware how “politically and historically significant” the march was. Leonard Mosala stressed their generational differences: these were not the people of Sharpeville. “Their aspiration level was far higher, their political sensitivity was deeper, and their anger matched [both].”

Related article:

The TRC held a special Soweto Day hearing, at which several witnesses said that the township was “on fire” that day. By 9am, approximately 10 000 had converged on Orlando West High School. Police formed an arc in front of the marchers, a tear gas canister was thrown into their midst, and they responded with stones. The police opened fire, and two pupils were fatally wounded, one of whom was Hector Peterson, aged 13. Pupils erected barricades, and attacked property, as “hundreds of police reinforcements” rushed in.

Murphy Morobe testified that the students resort to violence was a spontaneous expression of their anger and shock, never part of the plan. “It was the first time that many of us had [the] experience of tear gas … we tried to rally the students.”

The South African Police Riot Unit was set up in 1975, and there was already a “strong connection between riot control and counter-insurgency”. Swanepoel “became known for his brutality”: he was a founder of Koevoet in the Namibia-Angola region: “I made my mark. I let it be known to the rioters I would not tolerate what was happening. I used appropriate force … that broke the back of the organisers.”

Clashes continued for nearly two years after 16 June. The official toll between June 1976 and the end of February 1977 was 575 killed and 2 389 injured: probably an underestimation. Morobe and a number of other activists were detained in December 1976: “They interrogated us at John Vorster Square … to get statements [implicating] others … Students could not have planned this … There was clearly someone else other than you chaps who were involved in this,” they insisted.

Kassinga and the termination of apartheid’s military dominance

South Africa’s massive assault on Kassinga in 1978 was part of apartheid’s attempt (1975-1989) to assert dominance over Angola. It began just weeks after the Carnation Revolution in Lisbon on 25 April 1974, and the liberation of Angola under an MPLA government on 11 May 1975. On 14 October, encouraged by the United States, South African forces invaded from the south, and rapidly advanced on an unprepared Luanda. Thanks to strong and prompt military assistance from Cuba, the apartheid forces were forced to withdraw, defeated and humiliated by a small socialist island and an African liberation movement, in late March 1976.

Kassinga is 200kms north of the Namibian border. It was one of Swapo’s principal bases, with about 800 personnel in camp. It was also the main medical centre for seriously injured guerrillas. As the SADF’s General Viljoen noted, Kassinga “was not heavily defended”, and the nearest Angolan and Cuban forces were 15kms away. The target “lent itself to the maximum use of airpower and the infliction of maximum casualties”. It was “both a military base and a refugee camp … and it housed considerable numbers of civilians”.

The assault began at 8am on 4 May 1978. Four Canberra bombers attacked. One minute later four Buccaneers dropped seven 400kg fragmentation bombs, a weapon intended to wound and kill indiscriminately. Some 370 paratroopers followed. The ground forces were commanded by Colonel Jan Breytenbach of 32 Battalion. As the operation proceeded, leaders not only failed to attend to the wounded, but shot many out of hand: as an anonymous soldier reported: “There was just too many wounded … I was given an AK-47 and instructed to kill … Some were conscious … We found this woman clutching her screaming baby … we saw the terrible wounds inflicted by an Air Force bomb … She looked at me. I can never describe what it did to me.” The dead were hastily buried in two mass graves. By evening the assault was complete. The TRC believed that some 1 200 people died, and over 600 people were wounded. In two testimonies, Lieutenant Johan Verster said: “Kassinga was probably the most bloody exercise we ever launched … It was a terrible thing … It’s damaged my life.” For Geldenhuys “it was a jewel of military craftsmanship”.

Related article:

Military brutality prevailed on the Namibia-Angola border. Koevoet operated on a bounty basis, where members were paid for killings and for seizures of enemy weapons: kopgeld [head money]. Torture was rife. Once information was extracted, prisoners were shot and buried. “Bodies were often tied to armoured vehicles and the men would drive round with them for a week with their skin being ripped off.” Suicides were frequent.

The TRC found Prime Minister Vorster principally responsible for the Kassinga atrocity as head of state: Minister of Defence PW Botha was responsible as political head of the SADF and Magnus Malan responsible as chief of the SADF.

The effects of South Africa’s war on Angolan civilians were “devastating”. Unicef estimated that, between 1980 and 1985, “at least 100 000 Angolans died” mainly as a result of war-related famine. Between 1981 and 1988, Unicef thought “333 000 Angolan children died of unnatural causes”.

Related article:

Pretoria’s regional dominance was brought to an appropriate end in the skies over Cuito Cuanavale in 1988. From the previous year, Cuba’s air capacity in the south of Angola was strengthened and extended: building two new airstrips, and installing a radar network linking together 150 SAM-8 missile batteries. The Soviet Union supplied Angola with MiG-23 fighters, assault helicopters and T-64 tanks: Soviet military aid was worth $15 billion by that year. Crucially too Cuba sent its most experienced combat pilots. When Cuba gained air superiority over the battlefield at the end of 1987, it neutralised Pretoria’s prized long-range artillery: every shot fired by a G-5 could be located and destroyed. Breytenbach said that South Africa’s attack on Cuito was “brought to a grinding and definite halt”.

Cuba became a full participant in negotiations for Namibian independence, able to determine outcomes: the complete withdrawal of South African forces would be completed not later than September 1988. Namibia became independent in March 1990. In May 1991 the last Cuban troops flew home.

Nelson Mandela, speaking in Havana, in 1991, recognised the significance of these conjoined military-political advances: without Cuito Cuanavale “our organisations would not have been legalised. The defeat of the racist army … made it possible for me to be with you today. Cuito Cuanavale marks the divide in the struggle for the liberation of southern Africa.” The ANC’s armed struggle had been a bitter, notable irrelevance.

Lawlessness and terror

From the mid-1980s, a climate of “state lawlessness” prevailed, as the Botha regime abandoned any pretence of adherence to the rule of law. This was manifested as “emergency executive decree became the chosen method of government”. It was also expressed through the reliance on torture and terror against popular democratic organisation. It was sanctioned and promoted at the highest level. It was seen when John Vorster adopted a “shoot-to-kill” policy to “maintain order at all costs” at the start of the Soweto uprising.

Covert actions, such as “Operation Zero Zero” where eight young East Rand activists were given booby-trapped grenades by a Vlakplaas operative (established in 1979 with askaris or turned ANC or PAC, it evolved into the special forces of the Security Branch under Colonel Eugene de Kock): its activities were “sanctioned at the highest levels of government”.

Internal political mobilisation was targeted, and state torture was routinised. In 1986 groups like the Alexandra Consumer Boycott Committee demanded the withdrawal of the SADF from townships. Late April saw “the emergence of ‘street committees’, as well as ‘alternative structures’ of community organisation”. On the night of 22 April, police attacked the homes of activists, and “five people died”. The Alexandra Action Committee announced on 30 April that “people’s power” had been established there. But the nationwide state of emergency decree, of 12 June, ended that initiative then.

Police torture was “endememic”. Youths 13 to 24 years old were likely victims, especially those “who held local leadership positions”. In the 1980s, state torture was punitive, sustained and intense. Jacob Khoali was a member of the Katlehong Residents Action Committee, a UDF affiliate. He was detained for 14 days, then arrested again after June 1985. He was taken to a private house and subjected to “helicopter torture” and electric shocks. As a result, both Khoali’s legs were amputated above the knee.

Related article:

Through 1985, resistance to apartheid was often closely interlinked with organised democratisation. The UDF was formed two years earlier. The Pebco Three showed this association in May 1985. Sipho Hashe, Champion Galela and Qaqawuli Godolozi, members of the Port Elizabeth Black Civic Organisation (Pebco), were abducted on 11 May by the Security Branch, taken to Port Chalmers and killed. Askaris from Vlakplaas assisted in the operation. Galela was tortured to death. With his body in full view, Hashe was brought in and “subjected to unremitting torture until he too died”. Godolozi spent the night in a garage with the bodies and the following morning suffered the same fate. Their remains were thrown into the Fish River.

Shortly before the killing, “a high-powered political delegation” including President Botha and Ministers Vlok and Malan visited the rebellious Eastern Cape. Numerous security personnel testified that they were informed that the area “had to be stabilised at all costs”. Harold Snyman of the Port Elizabeth Security Branch reported that they must “act in a drastic way to neutralise activists”. The characteristic apartheid instruction: order must be restored at all costs.

Six weeks later, in late June 1985, the Cradock Four, Matthew Goniwe, Fort Calata, Sparro (or Sparrow) Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlauli, were targeted. Goniwe was the popular principal of the Lingelihle Secondary School: when he was threatened with an enforced transfer, a boycott by around 7 000 students lasted over 15 months. He was “instrumental” in forming the Cradock Residents Association (Cradora) in 1983, and became its first chairperson, assisted by Calata, fellow teacher and community organiser.

At the end of March 1984, Goniwe and Calata were detained, effectively for six months. Amidst various community actions and state repression, a “successful seven-day boycott of white shops took place in Cradock in August”. On 10 October, Goniwe and Calata were released “to a hero’s welcome”. The TRC said that Cradora “enjoyed widespread support from most of the township’s 20 000 residents”.

Related article:

The Cradock Four epitomised the association between broad community action and advanced democratisation. On 3 March 1985, Matthew Goniwe was elected to the UDF’s Eastern Cape regional executive as rural organiser. He “helped establish civic structures” in towns all across the region “us[ing] the same methods as organisations in Cradock”. Cradock itself was doubly distinguished: it was seen as “a model of organisation by the UDF”. The “effectiveness of Goniwe’s organisational methods” were also noted by the state: the security forces saw “Goniwe in particular”, as “the epicentre of revolutionary organisation in the sub-region”: General Joffel van der Westhuizen noted that Cradock was “the very first town [in South Africa] where they successfully implemented alternative structures [of government]”.

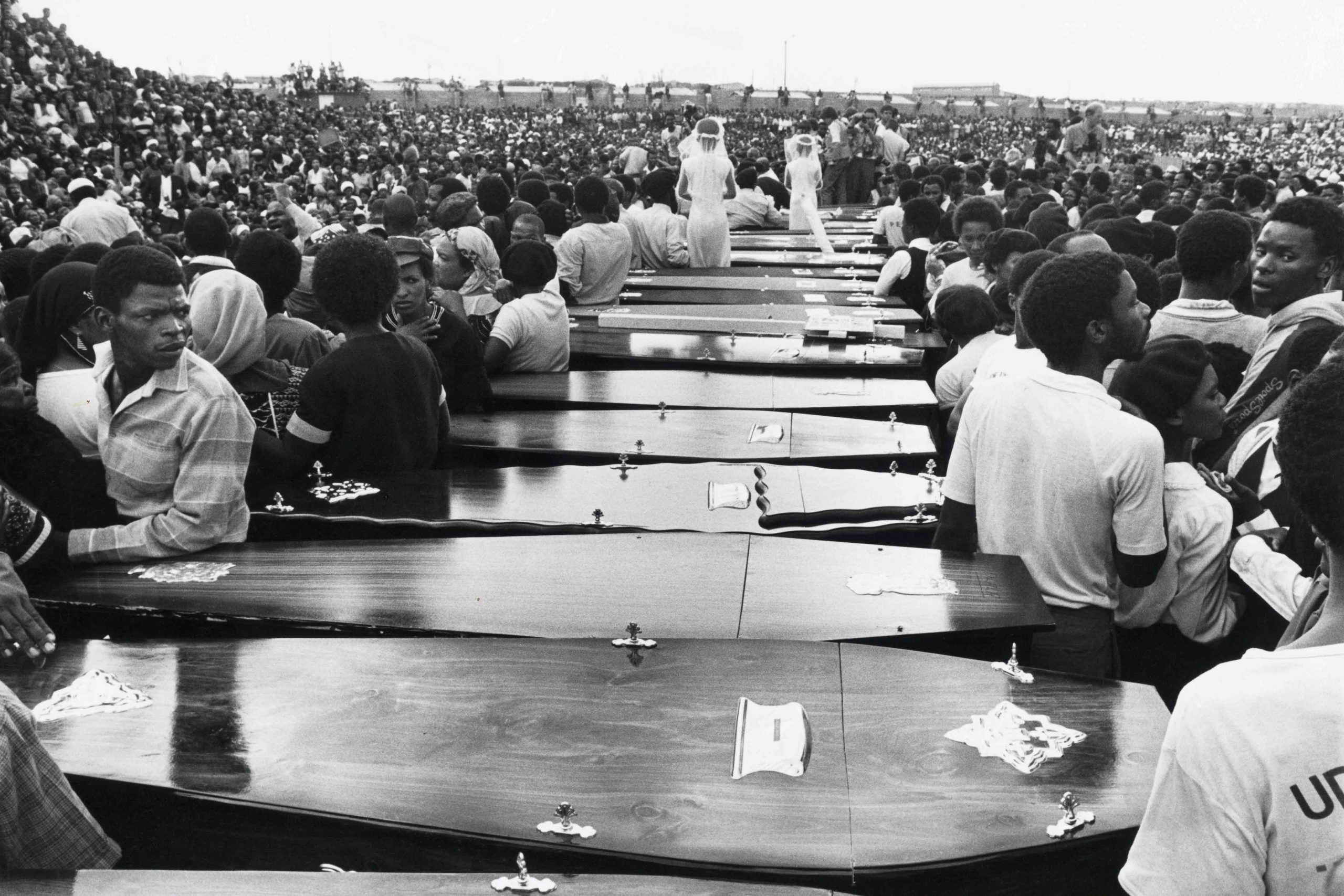

The Four were killed on 27 June 1985. They were “tortured by blowtorch”, stabbed many times, and “the fingers of Fort Calata’s left hand were severed”. His wife, Nomonde Calata, described how she had identified her husband’s mutilated body: “his hair was plucked out, his tongue pulled, his fingers cut, his calf bitten by a dog and there were wounds all over his body”. The bodies were “dumped in the veld near Port Elizabeth”. The Pebco and Craddock killings were only weeks apart, and both concerned “prominent UDF activists”. Sixty thousand people defied a banning order to attend the Four’s funeral on 21 July. That night a state of emergency was declared over most of the Eastern Cape.

Authorisation at the top: the crimes and the destruction of the records

General Nic van Rensberg, the commander of the police, instructed Eugene de Kock to carry out the “Motherwell Bombing”: the silencing of four black policemen attached to the Motherwell station in Port Elizabeth who had “threatened to expose their white colleagues” involvement in [the death of the Cradock Four]. So effective was the Vlakplaas network that security departments throughout the country used it, “often with the tacit support or outright connivance of cabinet-level politicians”.

De Kock saw himself as “a crusader” of apartheid: he was the commander of the headquarters of the “dirty war” waged at home and abroad, and he regularly “went out with his men”. In this war there were for him “no rules except to win”. After he was arrested in May 1994, he was criminally charged and sentenced to 212 years jail. When he testified before the TRC, Albie Sachs, now a Constitutional Court judge, thought he was telling the truth “like no one else”. Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela believed he “made an extraordinary contribution to the TRC”. Most of the security police “and certainly all the police generals who applied for amnesty were forced to do so as a result of de Kock’s disclosures … Yet they still walk free.”

During the height of the wars, De Kock had received the country’s highest national award for bravery, the Silver Star, and “his unit had been allocated millions in secret funds”. FW de Klerk’s relation to the TRC and the truth was the opposite of De Kock’s. In a great reversal, the Nobel laureate portrayed himself as the man who dismantled apartheid, and insisted “my hands are clean”.

Related article:

De Kock was aware of the hypocrisy and the abnegation of the state leaders. Gobodo-Madikizela learned of his bitterness “at all those who gave me orders … [and] the person who sticks most of all in my throat is former president FW de Klerk”.

The TRC found that the destruction of state records was done systematically, affecting a huge body of material. The sabotage began in the 1980s, and was coordinated and sanctioned by the Cabinet. The destruction undermined the TRC’s work “more than any other single factor”. In 1993, the Cabinet expanded the process to “all state offices” to eliminate evidence of gross human rights violations. By May 1994, a “massive deletion of state documentary memory” had been achieved.

An accompaniment and consequence was the state’s near loss of control over the military in the run up to the country’s first democratic elections. From the start of formal negotiations in mid-1990 and April 1994, some 14 000 people died in “politically related incidents”. In December 1993, a Transitional Executive Council was installed, but the Inkatha Freedom Party had also been established in July 1990, and violence massively escalated. There were, additionally, “military-style attacks on trains” (in which some 572 people died), massacres and assassinations.

Related article:

Among apartheid’s collaborators in domestic violence few were more deadly than Inkatha and its leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi. The TRC found Inkatha responsible for some 3 800 killings in the KZN and Natal areas during its mandate period, compared with about 1 100 attributed to the ANC and 700 to the police. Responsibility rested firmly with Buthelezi as the leader of the party, the KZN government and the KZN police: his was a one-party dictatorship. Statistics established Inkatha as the foremost perpetrator of gross human rights violations in the region, and led the TRC to describe Buthelezi as an ally of the apartheid state. But the counting in the founding 1994 elections had seen the Inkatha Freedom Party being awarded 10.5% of the national vote and its blood-stained leader becoming home minister (De Klerk became deputy president). The dominant ANC now favoured détente, and looked to possible unity between themselves and Inkatha. Elite impunity was strengthened and justice for Buthelezi’s victims was sacrificed.

The TRC process was also deeply inequitable: two life sentences for De Kock and a Nobel Prize for his commander-in-chief. For top perpetrators, really no trials resulted. The National Prosecuting Authority “recently decided” to reopen apartheid-era inquests and “pursue prosecutions”. But it is the foot soldiers who are currently being investigated.

Time is short: perpetrators are dying, and the culpability of leaders like De Klerk and Buthelezi is recorded.

This is an edited version of a longer article first published by CounterPunch.