The artistry of Joseph Shabalala

Ladysmith Black Mambazo continues seamlessly thanks to the foresight of its founder, who leaves a legacy for his sons and continues to inspire others from his hometown.

Author:

19 February 2020

Film stars and famous musicians left bouquets of flowers and exquisitely worded notes wishing them well in their hotel rooms, Kenny Rogers and Whoopi Goldberg included. Producer Quincy Jones enthusiastically warmed up to their music as he flew from Los Angeles in California to watch them perform in Rotterdam in The Netherlands. Jane Fonda cried during a performance and, the following day, brought her children along, who were also overcome with emotion.

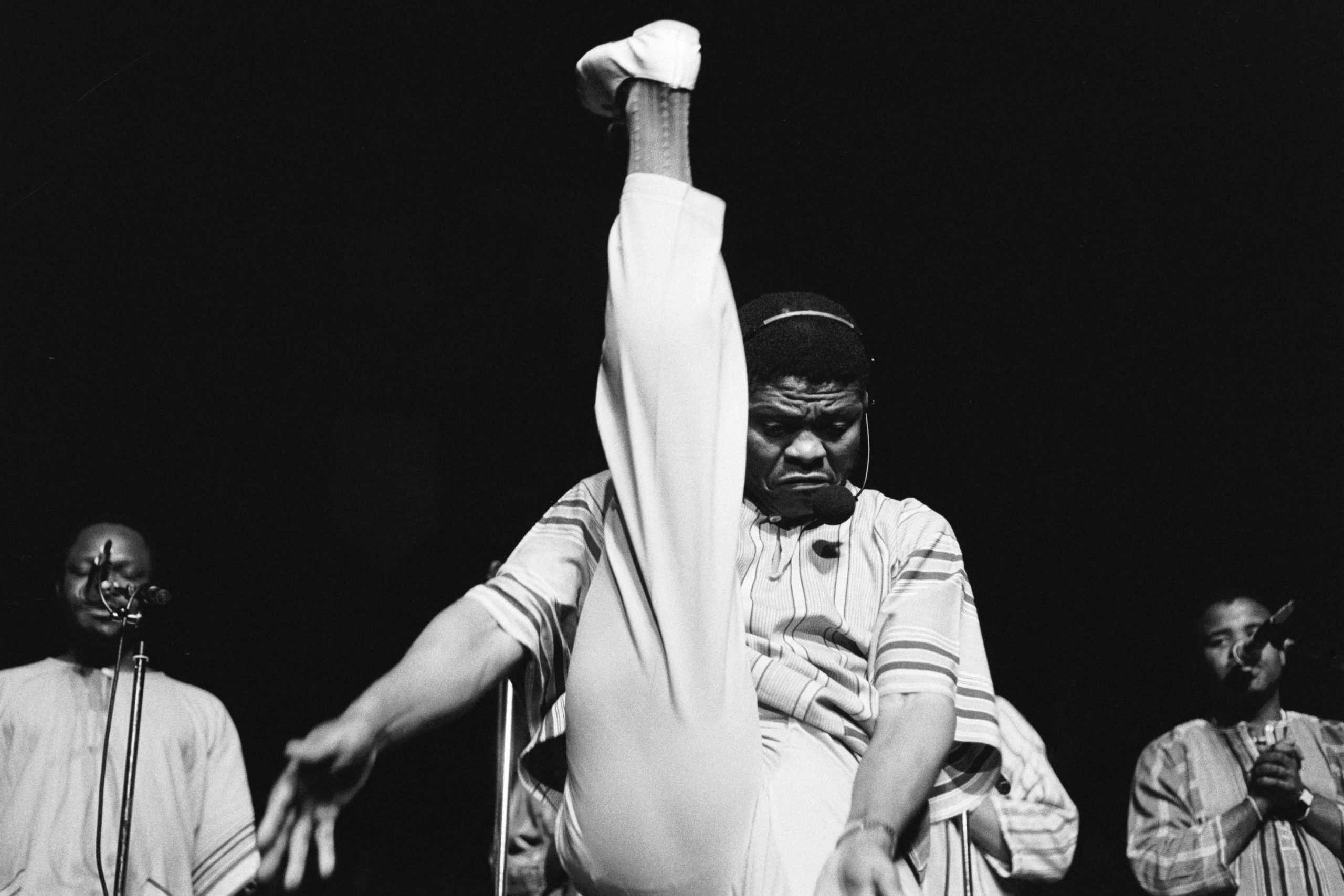

Wherever the group performed, they touched hearts with their gentle vocals and graceful stalking movements. The spectacle was something out of this world, almost surreal for Western audiences introduced to the sounds of isicathamiya.

Related article:

This was in 1987 and Ladysmith Black Mambazo were on top of their game. Their Graceland tour with American musician Paul Simon was in town and the world was their oyster. The red carpets and state banquets were worlds apart from the racial segregation in South Africa, a far cry from the smell of cow dung and fireplace smoke, and the bleating of goats amid the green grass of their hometown.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo have performed on global stages with some of the best: Michael Jackson, Andreas Vollenweider, Dolly Parton, Lou Rawls, Joan Baez, Stevie Wonder and the English Chamber Orchestra.

When news broke that the soft-spoken and charismatic founder of the world’s most famous a cappella vocal ensemble had died, one couldn’t help but recall the ominous and prophetic epilogue in his version of the Bob Dylan classic Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door: “Brothers and sisters, see you in heaven, sobonan’ezulwini,” he sang on the 1997 album Heavenly, which features the queen of country music, Dolly Parton.

Released a decade after the milestone Graceland tour, the album is an exquisitely crafted work that marries some of the best-known folk and pop classics from the West with some of Shabalala’s famous gospel songs.

Purists and conservatives can still enjoy reworked versions such as Billy Joel’s The River of Dreams, Sam Cooke’s Chain Gang and People Get Ready by Curtis Mayfield. Heavenly is a smorgasbord of delightful songs from various musical traditions, an excellent illustration of an artist who embraced diverse international styles while retaining his heritage. In his own words, “This is cultural music that is not only a gift for the black man but also a present from God for all generations to come.”

The sheer beauty and spiritually uplifting efficacy of Shabalala’s music defies the background against which it was created.

The world that made Shabalala’s sound

The music was born in the context of land dispossession, social dislocation and political oppression under colonial and apartheid rules. Shabalala was born on land that belonged to his Zulu forebears but was conquered under the British colonial administration.

The suppression of the Bambatha Rebellion in 1906 marked the end of the anti-colonial wars of resistance and the consolidation of white rule in the land of the Zulus. That’s how Shabalala’s grandparents and parents were reduced to being tenants on a white-owned farm, a semi-slavery arrangement that required the family, including children, to perform farm labour for survival.

On the other hand, the discovery of diamonds and gold in Kimberley and on the Reef forced able-bodied young men from their homes to work in the mines for slave wages. Hugh Masekela’s Stimela has since become a definitive musical reference for the migrant labour system, its manifestation and tragic social consequences. But Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s Isitimela – from a 1974 album of the same name – is equally evocative as it recounts the pain and tears of parents as the train separates them from their sons.

It’s an autobiographical piece that recalls Shabalala’s life in the 1950s, when he, his brothers and cousins went to Durban to find employment in textile factories and the construction industry. Nomathemba, his most popular song that was first recorded for their debut album, Amabutho (1973), is a love song on the surface. But it is actually a lament for the young men who “would be swallowed by the mine dumps”, those who would be corrupted by city life and forget their rural roots and the loved ones they had left behind.

‘Night music’

As migrant workers in the city, they found solace in musical traditions. That’s how the Zulu a cappella idiom known at the time as ngoma’busuku – literally “night music” – was born in mine compounds, hostels, backyard servants’ cottages and similar.

Solomon Linda and his Evening Birds’ 1939 global phenomenon, Mbube, later replaced ngoma’busuku as the preferred name for the genre. The song was recorded two years before Shabalala was born, but it became a defining influence as it took on various guises in the hands of different artists. As one of the most recognisable and most recorded songs to come out of South Africa, one of the group’s various recordings can be heard on their 1999 album, In Harmony.

Mbube also became an obsolete term and only continues to be useful for musicologists and social historians. It was replaced by isicathamiya, from the Zulu word cathama, meaning to “tread softly”. It’s an apt word to describe the gentle and graceful moves and sound that defines the genre. It was a necessary approach in a white man’s world where indlamu, the raw and robust traditional Zulu dance equivalent, was forbidden. Isicathamiya’s message was about being cognisant of the rules that defined black existence. The message was, “tread carefully, as if on your toes like a cat whose steps don’t make a sound”.

As a vocal style, it’s the music of nostalgic men who are missing their rural lifestyle of herding cattle, courting maidens, stick-fighting, wedding celebrations and the like. It’s music that is inspired by a strange and forbidding urban landscape. It’s an idiom that celebrates and mourns at the same time. It’s a haunting and mesmerising sound, the music that seduced Paul Simon and took the world by storm.

Inspiring legacy

The story of Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Joseph Shabalala tells how music can emancipate an artist from a working-class condition and catapult him to international superstardom. But it speaks of more, too, when considering the birth, shape and impact of his sound and artistry.

The group’s exceptional success has inspired subsequent generations of isicathamiya musicians – and they are many. His sons are obvious examples, a shining product of a visionary leader with a succession plan. Most groups disintegrate when the founder dies. But Ladysmith Black Mambazo remains strong on global stages, an inspiring illustration of a flourishing legacy.

Related article:

Outside family circles but from the same town are the lesser-known but successful Ladysmith Abafana Bezamanani. For 10 years, New York-based musician, producer and promoter Rudi Mbele and his sister Cosbie Mbele have organised shows for the 11-member vocal ensemble.

They have released three albums and are scheduled to perform in the United States during next year’s Black History Month, held in February, doing shows in New York City, New Jersey and Long Island.

Another a cappella group, the Motherland Messengers, is scheduled to perform during this year’s Black History Month in New York, on Friday 21 February.

Also worthy of mention is The Soil, a youthful and popular a cappella trio that features Ladysmith Black Mambazo on their second album, Nostalgic Moments (2014).

Joseph Shabala’s artistry, born in dreams, has a solid and enduring legacy. It is music rooted in history that is thriving in the present and insistently propelling itself towards the future.