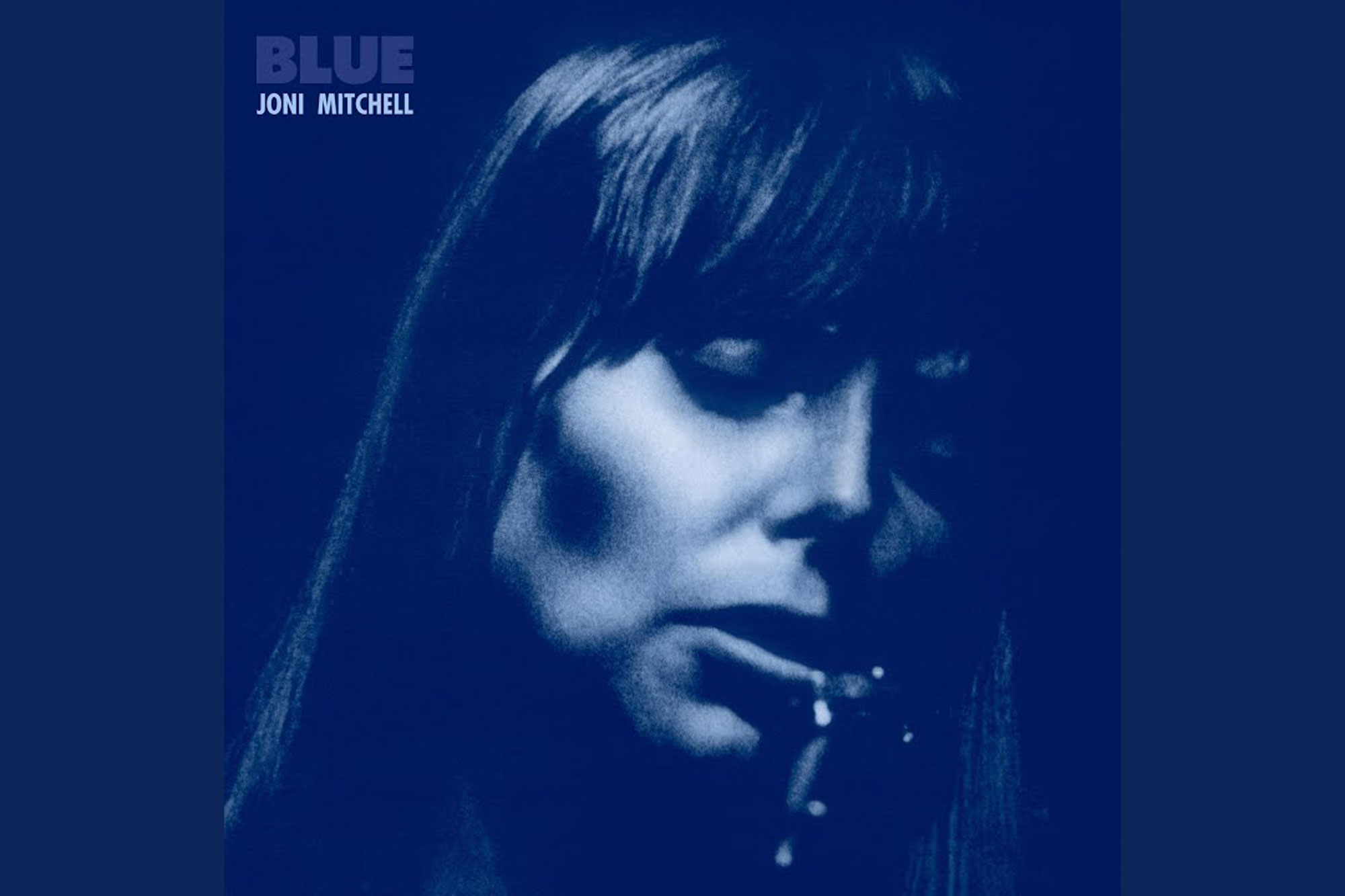

The bitterest sweetness of ‘Blue’

Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, released 50 years ago, was a public reckoning with private grief and regret. But it was also a watershed commentary on the utopianism of the counterculture.

Author:

29 June 2021

When I first heard Blue, I was 22 and I had no money, no job, no girlfriend, no car and no clue. At any given moment, my dank Woodstock digs in Cape Town were terrorised either by the howling southeaster or by a cat-sized rat, depending who was on shift. But at least my human housemate kept a turntable in the gloom of our lounge, and his LP collection included Blue. I spun it dozens of times in a couple of days.

Joni Mitchell was 27 when Blue was released. Unlike me at 22, she had dramatic problems – not the generic torpor of a BA graduate with a rat under his bed.

For one thing, she was aching hard for the six-year-old daughter she had given up for adoption at 21. At the time, in 1965, she was broke, an art student playing folk clubs in Calgary, Canada. She couldn’t afford a baby, in every sense. She wrote Urge for Going on a train journey with her baby’s father, a lantern-jawed classmate called Brad MacMath. Turns out they both felt that urge, and split up before the baby was born. And she gave the child up to a nice, bourgeois Calgary family.

Related article:

Cut to 1971 and Joni Mitchell was Joni Mitchell. She was a rock star, with a brief marriage of convenience behind her – and rich enough to care for a vanload of kids. But it was too late to take her child back. She couldn’t bring herself to tell the story openly, to break the spell of obligatory shame extracted by late high patriarchy from the mothers of illegitimate children – despite not actually feeling that shame.

Only in the late 1990s did Mitchell trace and reunite with her daughter, Kilauren Gibb, and spoke publicly about her. Until then, she hid her secret in plain sight, in the not-so-cryptic lyrics of Little Green, the third song on Side A:

Child with a child pretending

Weary of lies you are sending home

So you sign all the papers in the family name

You’re sad and you’re sorry, but you’re not ashamed

Little green, have a happy ending.

The songs on Blue are not all as razor-sad as Little Green. The whole record is embossed with sweetness, but the thematic binding is bitter: the songs form a twisting essay on the pros and cons of abandoning the people you love – children and lovers alike – in pursuit of artistic and erotic sovereignty. A Case of You is (possibly) about leaving James Taylor (or Leonard Cohen). My Old Man and River are about leaving Graham Nash.

Half of Mitchell wants us to forgive her for making these painful exits – and half of her wants us to shut up and listen to her own self-judgements. “During the making of Blue I was so thin-skinned that if anybody looked at me I would burst into tears,” she remembers in the documentary Woman of Heart and Mind.

In a feature in Rolling Stone magazine in 1979, she told Cameron Crowe that she felt the album was a reckoning with the idiocy and certainties of youth.

“By the time of [Blue], I came to another turning point – that terrible opportunity that people are given in their lives. The day that they discover to the tips of their toes that they’re assholes [solemn moment, then a gale of laughter]. And you have to work on from there. And decide what your values are. Which parts of you are no longer really necessary. They belong to childhood’s end. Blue really was a turning point in a lot of ways.”

Buying solitude

In the final analysis, she decides on her own voice as the necessary part of herself. She chooses herself, despite her self-doubt. And the medium becomes the content of her argument: she was right to abandon her lovers and her daughter because she couldn’t have created this epic thing, this diary of decadence and anguish, if she had stayed.

The grandeur of that implied resolution – that she buys her solitude with her art, and vice versa – is a big part of what makes Blue such a resounding feminist moment. Her radicalism was expressed both in her confessional transparency and in an ambitious hardness that her transparency revealed.

At 27, miserable or not, she had no plans to go the way of Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, who died at that age. She would not fold or retreat. She would resist oppressive authority, but she would not drown in the turbulence of resistance, as so many others were doing in the wild milieu of Laurel Canyon, the upscale hippie district of Los Angeles where she lived. In the title song, Mitchell considers the addiction-addled shadows of a darkening counterculture, grimly revising the sentimentality of Woodstock, written two years earlier:

Acid, booze and ass

Needles, guns and grass

Lots of laughs, lots of laughs

Everybody’s saying that hell’s the hippest way to go

Well, I don’t think so

But I’m gonna take a look around it though.

She wasn’t a puritan or a killjoy, though. She allowed herself bouts of decadent reverie. A year before writing and recording Blue, she left Nash in the Canyon and bummed around Spain, Greece and Paris for a while. She sent Nash a telegram from Crete that ended with the line: “If you hold sand too tightly in your hand, it will run through your fingers.” Which was presumably the 1971 equivalent of ghosting someone. Being dumped with a haiku can’t be nice, but Nash took it on the chin.

She partied in a cave village in Crete with a hairy ginger lothario called Cary Raditz – the cane-carrying “red, red rogue” immortalised in the lyrics of Cary, who kept her camera to sell after she upped sticks for Paris. (Unsurprisingly, Raditz, like so many sketchy alpha-male hippies, mutated magically into an investment banker in the 1980s, albeit one who loved to meditate.)

Cary and California – the two ecstatically nostalgic songs about her European adventure – serve to steer Blue out of boringly maudlin territory. Mitchell’s flair for delight is her secret weapon. She hurts you, and then she tickles you.

‘Kind of like a man’

Bob Dylan was also hard, and he seemed to have noted Mitchell’s kindred hardness, her seizure of the creative independence and arrogance, the licence to be “irresponsible”, that the reigning culture granted only to male artists. He described Mitchell’s self-liberation in perversely sexist terms, but she wasn’t too bothered, as she recalled in Brian Hinton’s biography, Both Sides Now (1996).

“They asked him about women in the business and he said, ‘Oh, they all tart themselves up,’ and the interviewer said, ‘Even Joni Mitchell?’ And he said, ‘I love Joni Mitchell, but she’s’ – how did he put it? – ‘kinda like a man,’ or something. It was a backhanded compliment, I think, because I’m probably one of Bob’s best pace-runners as a poet. There aren’t that many good writers. There are a lot that are touted as good, but they’re not literature. They’re just pretty good for a songwriter.”

Related mixtape:

She wasn’t a pace runner, of course – she was running on a different racetrack. Dylan was not even really singing; he was writing peerlessly over chords. So he was doing one thing while Mitchell was doing five things. What she did echo from Dylan was his destruction of the established norms about what a popular song is, and how honest it can be. They both wanted to destroy the formulaic posturings of genre, the emotional evasions of persona, though both might not always have achieved that destruction. She was particularly awed by the brutality of his score-settling in Positively 4th Street.

“There came a point when I heard [a Dylan song called Positively 4th Street] and I thought, ‘Oh my God, you can write about anything in songs.’ It was like a revelation to me,” she said to Crowe.

The year of the waves

If Mitchell does have a true musical peer, then it is not Dylan but Paul Simon, whose musicianship, melodic invention and lyrical chops are all in Mitchell’s league. They both spent the coming decades exploding the boundaries of folk music and their own cultures.

Simon’s solo career would only start in earnest in 1972, but Blue had some extremely good company in 1971. It was a year of inspired disenchantment, with scary new racetracks popping up all over popular music. David Bowie became his ungovernable, Friedrich Nietzsche-dabbling self with Hunky Dory; Marvin Gaye radicalised soul with What’s Going On; Led Zeppelin spawned metal with Led Zeppelin IV.

Related article:

All these small revolutions marked the musical end of the 1960s. Collectively, they decommissioned the seductive fantasies projected by the civil rights movement, by psychedelia, by Motown. That broad wave of visionary utopianism, vital and powerful but often laced with denial, had outlasted its purpose.

In its place, in Mitchell’s immortal telling, came adulthood, terror and courage:

Hey, Blue, there’s a song for you

Ink on a pin

Underneath the skin

An empty space to fill in

Well, there’re so many sinking now

You’ve got to keep thinking

You can make it through these waves.