The cross-border families of northeast Mpumalanga

Migrants near the border between South Africa, eSwatini and Mozambique walk a fine line, but it is family members living with an impairment who struggle most.

Author:

3 December 2020

Living in a rudimentary shack with a dirt floor at the back of his brother’s yard, Shadrack Mkukuli, 58, still carries the physical and psychological scars of the civil war in Mozambique, which ended in 1992.

Mkukuli’s leg had to be amputated after he was injured in an attack on a train in 1984. After losing a number of family members in the war, it was the murder of his brother that prompted family members already living in the Nkomazi area in northeast Mpumalanga in South Africa to send a relative across the border and bring him to South Africa.

In clear detail, Mkukuli described the day of the attack on his train by the Mozambican National Resistance (Renamo) that left him maimed.

“In 1984, I was working at Spoornet [the South African Transport Services] in Mozambique. That’s when I got injured. I was working on the train and Renamo planted bombs on the train. When it exploded, that’s when I got injured. After the bombs exploded, they attacked the train with guns.”

Mkukuli is a quiet man with a gentle smile. But when he started talking about that day, he straightened himself in his chair as his smile faded and his eyes widened. “Many, many people died that day. But myself, I’m lucky, I just lost my leg,” he said. “So many people died in my face. They shot them in front of me.”

During the 15-year civil war, Mkukuli lost numerous family members, including his father, grandmother and uncle. But it was the killing of his younger brother that had the biggest impact on him.

“I saw the attacks. I can’t forget it. My brother, while he was sleeping, they came into the house and shot him to death while he was sleeping,” Mkukuli said.

Only after he arrived in South Africa, in January 1989, was he able to get a prosthetic leg, having previously relied on crutches. He still uses the same prosthetic. It is old and cracked, but Mkukuli has been unable to get it replaced.

His legal status and the fact that he never applied for asylum on his arrival means he has been living on the periphery of society in Nkomazi, making it difficult for him to access basic services such as healthcare. “I’m not feeling good. I don’t have an income. I can’t work, I’m suffering too much,” he said.

Settled and integrated

Mkukuli’s case is not unique to this area in South Africa, where regional cross-border migration has been a feature for centuries. Bordered by Mozambique to the east and eSwatini to the south, Nkomazi comprises many cross-border communities.

In a paper commissioned by the Nelson Mandela Foundation in 2009, titled The Dynamics of Social Cohesion Amidst Transnational Spaces, Ken Mutuma writes that many Mozambican residents who remain in the area are former refugees who fled the civil war in their country. Today, most of them are permanently settled and integrated into the community, speaking local languages such as siSwati and isiNdebele fluently.

“Some have accessed South African identity documents through government amnesties and exemptions in 1996 and 1999/2000, but many, due to procedural weaknesses in the implementation of the amnesties, remain without documentation, unable to access basic services.

“This history of past migration from neighbouring states seems to have been conveniently forgotten, despite the fact that many of them have developed family ties in South Africa that stretch back decades,” Mutuma writes.

Migration has become a highly politicised issue in South Africa, with a number of politicians and political parties, such as the DA, the ANC, the African Transformation Movement and the South Africa First party, calling for tighter and stricter border controls during their most recent election campaigns. However, Mutuma writes, in border communities such as Nkomazi, people rarely travel through formal border posts “but mainly through informal border gates, especially between South Africa and these countries”.

Blurred nationalities

“Though few have immigration permits, these populations consider themselves South African due to historical community and family linkages,” writes Mutuma. “It is difficult to distinguish between South African and non-South African children, since they share languages (SeSwati [siSwati] and Shangaan), have relatives in South Africa and long-standing links in the district, and often have documentation from traditional authorities showing local residence.”

The family of Salbedze Mashabane, 50, is one such, with blurred nationalities and documentation. His wife, Sandra Mlima, 45, moved to South Africa with a relative after her parents died during the Mozambican Civil War.

Mlima, who is deaf, has a son, Sibusiso, 27, from a previous relationship. He has a visual impairment and a physical disability, yet Mashabane said neither of them ever struggled to access healthcare despite both of them being undocumented.

Mashabane, who was born with a physical disability in his left leg, and suffered a serious injury to his right leg after falling into a fire following an epileptic seizure, spends most of his days sitting on a mat under a big tree outside the two rooms where the family of nine lives.

Sitting in the blazing sun, Mashabane spends his days either weaving mats that he sells to make a little extra money, or crushing cans for hours on end. His youngest children collect these in the area, and he needs to fill nine or 10 50kg bags with crushed cans and other steel scrap to make between R1 000 and R1 500 a month.

“I’ve never worked because of my physical disability,” he said on a recent Thursday morning outside his house in Naas, in the Nkomazi municipality. “It becomes really difficult because I rely on the grant [I get] to look after my family.”

Of the seven children they have between them, the family only gets child grants of R400 for three. With this and Mashabane’s R1 800 disability grant, the family have to make it through the month.

One of the other big challenges for Mashabane and Mlima is to communicate with each other. Neither was able to learn an official sign language, and they communicate using signs and gestures they have learned from each other.

During the visit, Mashabane wanted Mlima to fetch a bucket and mop from their house, but it took a few attempts of gesturing and their sign language before she was able to understand his request. “She knows a bit of sign language and I am trying to learn a little bit from her,” he explained. Later on he clarified and said it wasn’t an official language, but something they developed between themselves.

‘Hidden’ from healthcare

Here in the Nkomazi municipality, many people struggle to access healthcare and other services because of their legal status in South Africa.

Research by the African Centre for Migration and Society at the University of the Witwatersrand found that most undocumented migrants, with or without disabilities, prefer to remain“hidden” or “invisible” when it comes to healthcare because they are afraid of being reported to immigration authorities and deported.

One of the authors of the report, Edward Govere, said: “Both citizens and migrants with disabilities struggle to access healthcare and other basic services in South Africa. Migrants with disabilities, however, face numerous challenges that are migration-related.”

Related article:

Other challenges faced by migrants include the lack of access to aids such as wheelchairs, crutches and prosthetic devices, difficulties in accessing residential care facilities and the fear of deportation.

Oupa Zitha, the chairperson of the Ehlanzeni Disability Forum, spends a lot of his time advocating for more awareness around people with disabilities and the challenges they face in the area. “You know, people are ignorant, especially the political leadership, until you remind them,” he said.

Creating space

Zitha was in a serious accident years ago while transporting sugar cane for a local mill. He was lucky to survive, but had to have his leg amputated and a tracheostomy performed.

It’s impossible for him to overlook migrants with disabilities. Instead, he focuses his work on all disabled people, because the migrant and South African communities are so intertwined in this region.

“In our communities, the challenges we face are being called names and feeling neglected by our communities. There is very much still a lot of work to be done in this community. Not just this community, but countrywide,” he said.

“[Politicians and civil servants] must not forget that in our country, whatever you are planning, and whatever budget we are planning, and whatever programmes we are planning, that there are people with disability and you need to create them a space.

“Even the buildings, they forget that there are people with disabilities who need to access these buildings. And these are just challenges for the South Africans. We need to do so much more work for migrants and help them at clinics when they don’t get the help they need.”

Although he has never had any problems accessing healthcare, nine-year-old Simphiwe Nkosi, who was born to a mother from eSwatini, has never been to school. Simphiwe’s mother died earlier this year and he now lives with his grandmother, Thulile Nkosi, 66, and his uncle, Mayibongwe Nkosi, 30, near the eSwatini border.

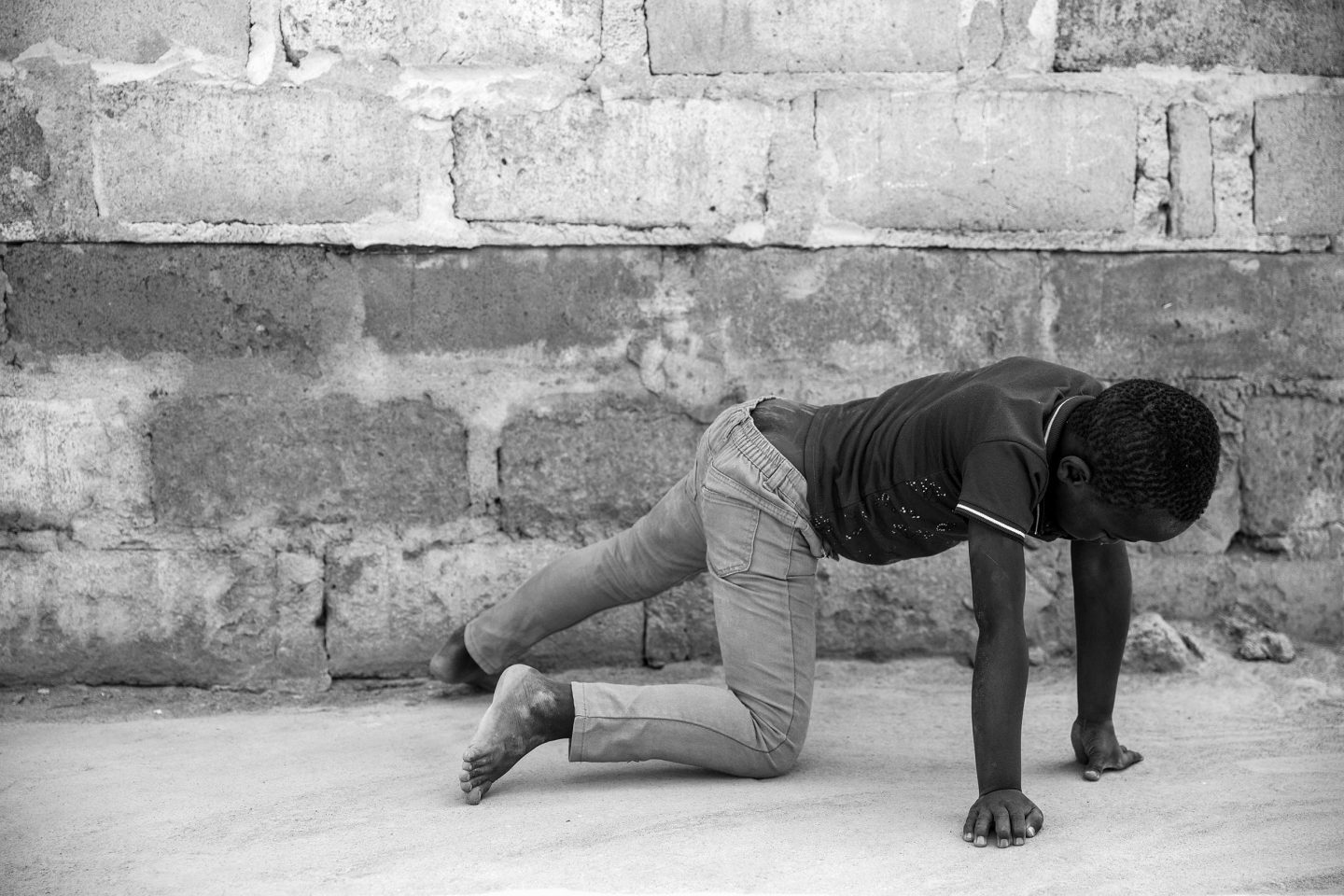

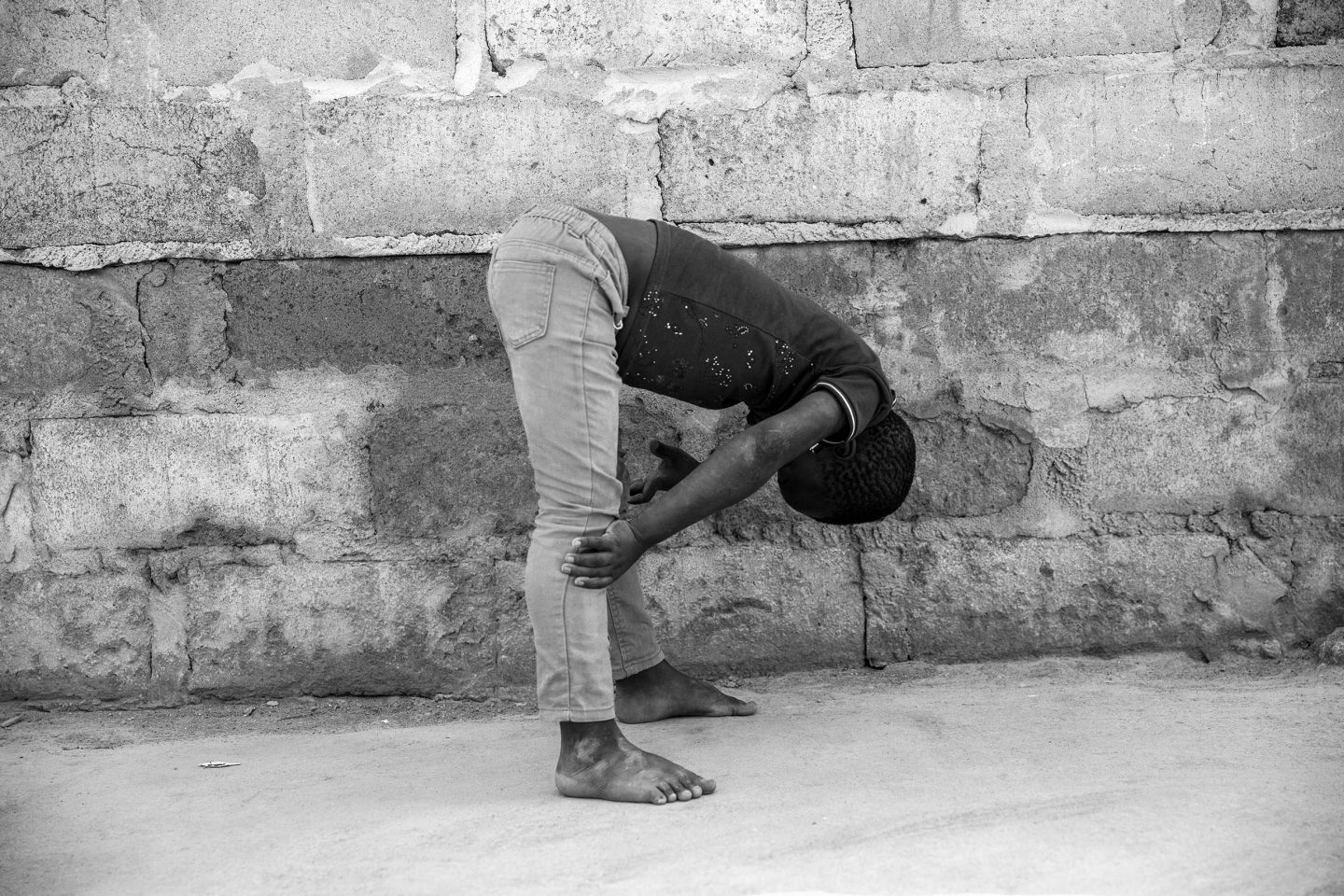

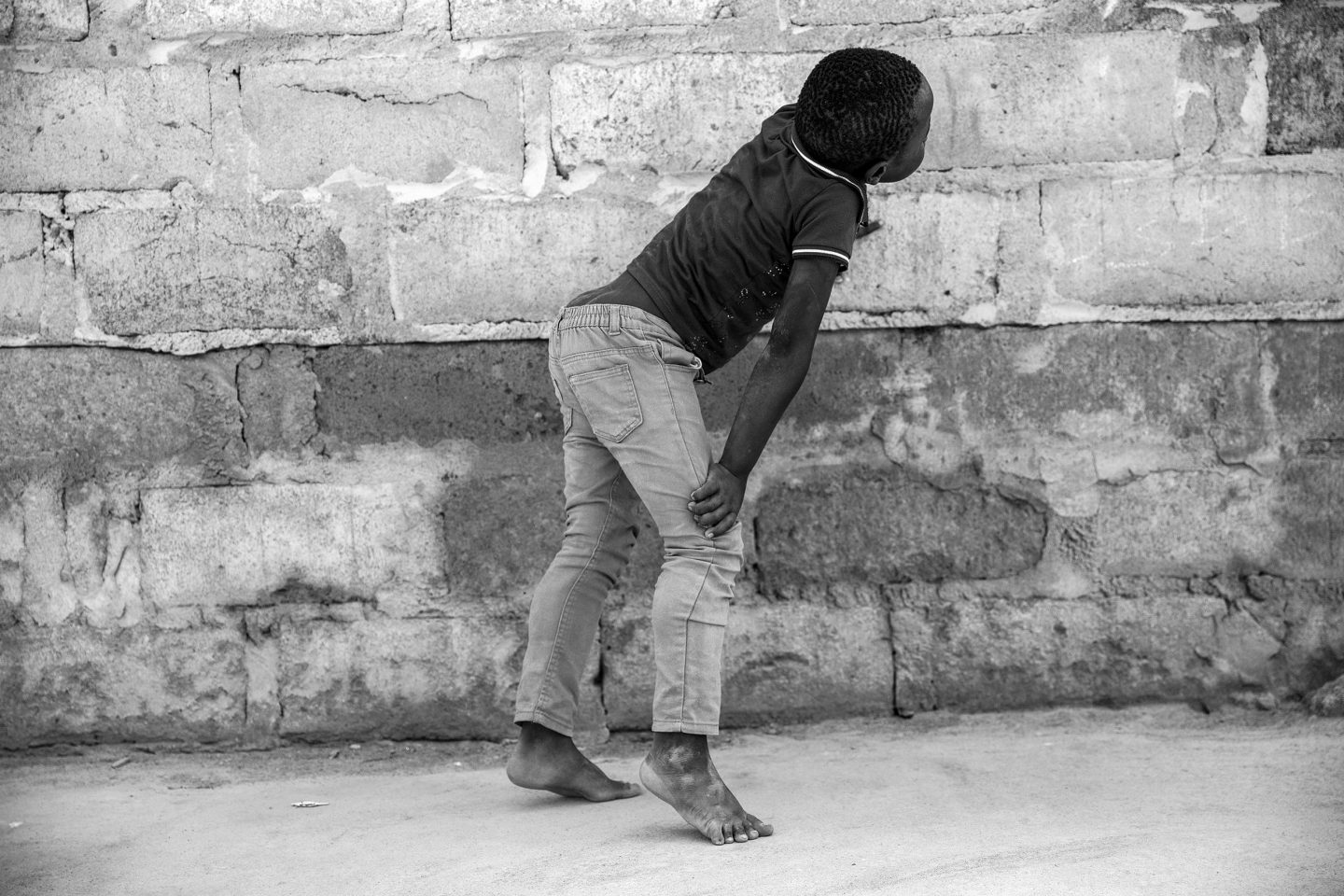

Simphiwe has a physical disability and struggles, among other things, to raise himself from a sitting position. First he shifts his weight to the side while getting on to his hands and knees. From there, he tries to straighten his legs while his hands support his weight on the floor. After that, it takes a lot of effort for him to straighten his back while he supports himself against a wall or with his hands on his knees.

Thulile Nkosi, who lives in a basic brick house, looks after him and some of her other grandchildren. In the dusty yard outside the house, Simphiwe battles to keep up with his cousins while they play in and around an old car wreck.

“The kid has a problem with walking and he doesn’t focus well,” Mayibongwe Nkosi said.

“The doctors never really told us what is wrong with him. They just provided us with some medication to make his body strong,” he said. “Simphiwe doesn’t go to school because he has epilepsy and we can’t get him into a special school.”

This project was undertaken in partnership with Wits University’s African Centre for Migration and Society and the International Organization for Migration, with funding from the Irish Embassy. This story is part of The Endless Journey – a series of stories about migrants with disabilities.