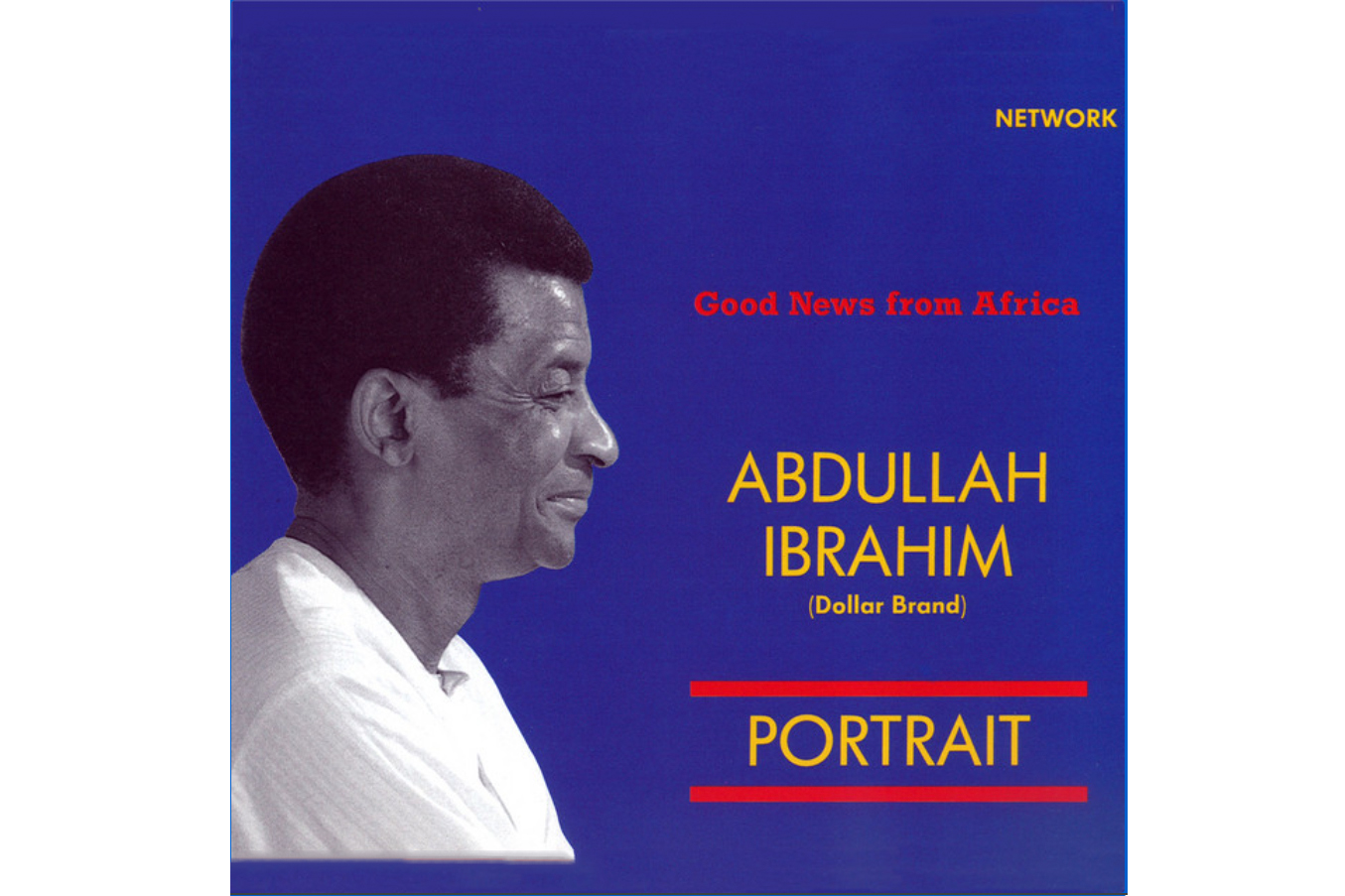

The divine message of ‘Good News From Africa’

Abdullah Ibrahim and Johnny Dyani’s 1973 album was the realisation of a journey in music and spirituality, combining Islamic and Xhosa influences to create something unique.

Author:

3 May 2022

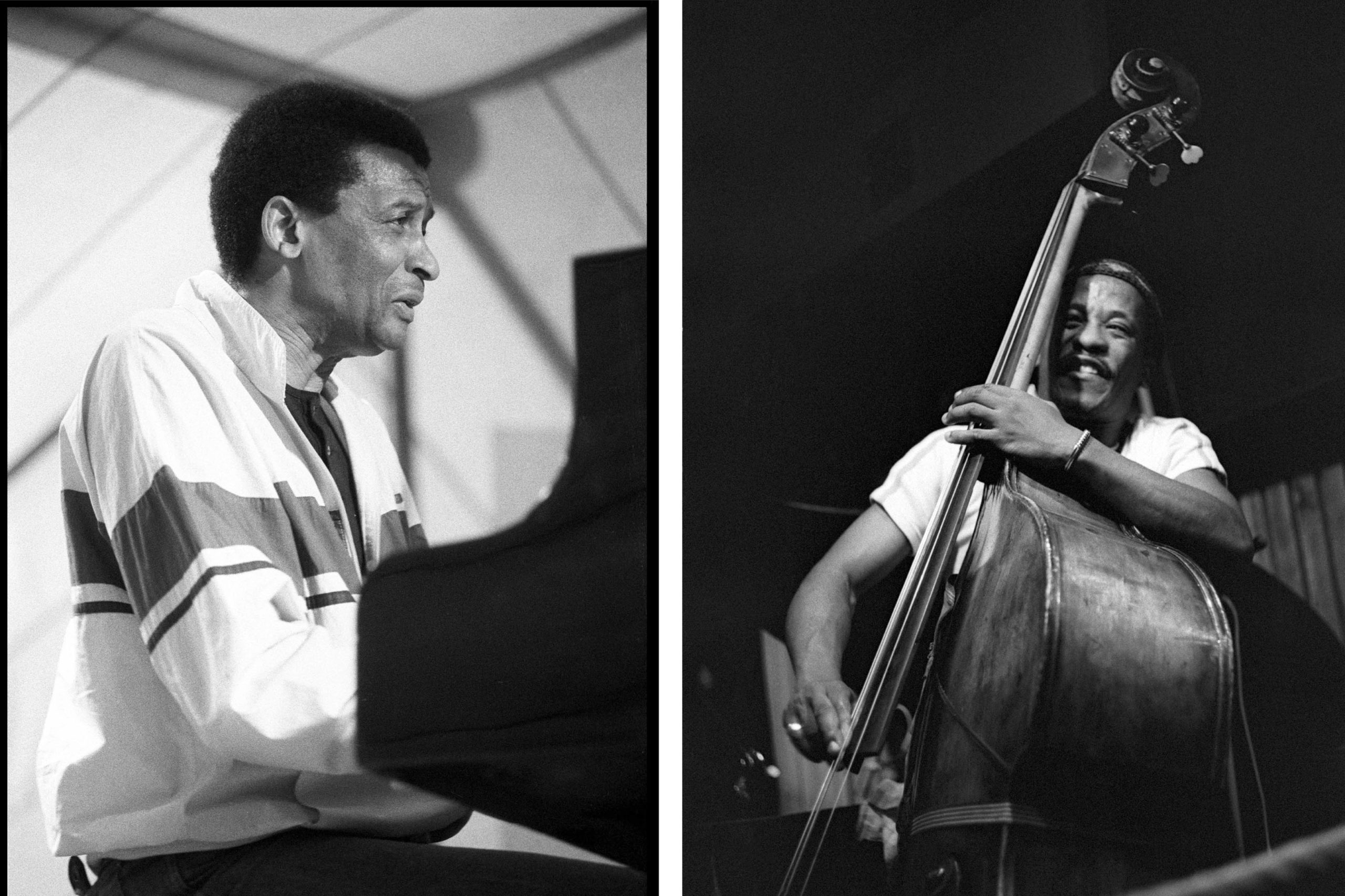

Pianist Abdullah Ibrahim and the great bassist and composer Johnny Dyani got together in 1973 to create Good News From Africa – a marvellous South African jazz record crafted to celebrate the Islamic and Christian faiths in the lives of people of the Cape. The six-track record is as much a personal celebration of newly found faith as it is an exploration of the complexity of identity in the area.

The duo wove a complex picture of the shared heritages connecting amaXhosa and communities the apartheid government designated as coloured, from antiquity through to modern history. The music they created mixes Islamic nasheeds, traditional African songs and expressions of early Africanist Christianity.

It is syncretic music, “performed with a fervour and depth of feeling rarely heard in or outside of jazz”, writes Brian Olewnick in an early review. Good News From Africa comprises six compositions by Ibrahim with Dyani on some key rearrangements of traditional pieces.

Related article:

The most remarkable among these is the opening track, Ntsikana’s Bell, which is a nod to the memory of Ntsikana ka Gaba, a pioneering voice in the formation of the early Africanist Christian movement in the Cape. Ntsikana is said to have been visited by angelic visions telling him to embrace Christ and learn how to read – which became central to his ministry. Notably, Ntsikana nurtured and proselytised a critical message in what he saw as the church’s subservient relationship to European culture. His mission launched a Christian tradition independent of European missionaries and colonial capture, forged through independent divine inspiration.

Dyani and Ibrahim’s project recalls Ntsikana in part because his methods echo that of the Islamic tradition. Ntsikana had no bell to call his flock of believers to prayer, so he used his voice. His call to prayer was similar to the adhan, the Islamic call to prayer a muezzin recites five times a day.

Related article:

The record includes compositions drawn directly from Islamic devotional rituals. Adhan & Allah-O-Akbar is the third track on the record, opening by lifting off in the traditional Islamic lilt. But, as it develops, the verses are vocalised in a mode firmly rooted in southern African tradition.

This was largely Dyani’s contribution, as Ibrahim recalled in an interview with Danish writer Lars Rasmussen. “It opened up a whole new dynamic. We shifted away from harmonic structures and played modally, the Xhosa modality … so with Johnny I touched on the Xhosa tradition, and it’s massive what you can do with it! We experienced it and expanded on it and it opened a freedom for us. It allowed us space. You play bebop, you fill out a space. When you play our music, you don’t play notes, you just play space!”

To fully appreciate both the musical power and the cultural significance of Good News From Africa, one needs to understand the personal transformations Dyani and Ibrahim underwent at the time of its making.

Personal transformations

Dyani moved to Denmark in 1972, where Ibrahim had built a strong musical foundation and a community of followers. Ibrahim had recently returned to Europe, after time back home in Cape Town in 1968 to look for personal meaning and healing. It was then that he changed his name from Dollar Brand to Abdullah Ibrahim. He had taken the shahada, the Muslim profession of faith – there is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his messenger.

In Denmark, the two musicians worked together on various bands, notably in Universal Silence with African-American trumpeter Don Cherry, and Brazilian percussionist Naná Vasconcelos and others. As a result of their deepening kinship, Dyani also took the shahada and embraced Islam. He took on the name Akhir, though never enforced its use in his public life and work.

Related article:

In Mbizo: A Book About Johnny Dyani, Rasmussen highlights the bassist’s devotion to his faith. “Wherever he went, he kept a well-worn copy of the Penguin Books edition of the NJ Dawood’s English translation of the Koran.” Ibrahim remembers faith being of “immense importance to [Dyani]”, too.

Dyani and Ibrahim’s relationship was built on their shared vision for music. Alongside their religious kinship, Ibrahim found freedom in Dyani’s bass and larger musical outlook. Ibrahim had found the bassist of his dreams in Dyani, as he told Rasmussen: “I developed the left hand because I couldn’t depend on bass players … but with Johnny it was possible to play the bass pattern, but I was also able to release it, because he was there. Very dependable! He gave us that foundation to work from and he really freed us.” This is akin to what Olewnick observed in Dyani’s bass playing. He describes it as “simply astonishing, never indulging in mere virtuosic displays but always probing, always deep”.

An expansive vision

Through the largeness of its vision, the music of Good News From Africa enlarges how we imagine Cape culture and its myriad convergent identities. By crafting a deliberately fugitive and expansive sonic register, the album plays with Islamic expression in a uniquely southern African cultural context.

Ibrahim’s personal story in part makes this possible. Born of a Mosotho father and a mother classified as coloured by the apartheid government, his biography stretches how Islam and the so-called Cape coloured community intersect – Ibrahim renders the adhan, the call to prayer, in isiXhosa mode, for instance. Suddenly, Cape Muslim culture is broadened, going beyond the Malay, Khoi and San influences. New lines emerge – Bengali, Malagasy and other streams from the expanse of the Indian Ocean and Swahili seas where Afro-Asian slaves and indentured labourers were captured and brought to the Cape.

“In a sense it was not only playing music, but reaffirming history,” Ibrahim tells Rasmussen. “We were actually sort of consolidating our background and experience … and we found out that it was valid.”

Reverence

In the South African jazz cannon, compositions created in reverence of God have a lofty pedigree. Among the better examples of devotions is Wakrazulwa, recently performed by Thandiswa Mazwai in her 2016 record Belede. She approached it as an ode to her friend and creative confidant Busi Mhlongo, who sang it in her devotional record, Amakholwa (Believers).

A more generalised expression of this idea can be found in spiritual compositions by contemporary musicians. For instance, Thandi Ntuli put out variations on umthandazo (prayer) in her debut and sophomore albums. Pianist Andile Yenana also performs a tender hymn, We Pray, on his debut album.

Related podcast:

Arguably the most consequential saxophonist and composer of his generation, Zim Ngqawana, opened his definitive record, Zimology, with a benediction, Mayenzeke, isiXhosa for “Thy will be done”. Among the younger crop of musicians working now, Iphupho Lika Biko stands out for the hymn, UThixo Ukhona (God is Real).

Yet, it is still possible to argue that none have risen to meet the larger cultural questions addressed in Good News From Africa. Ibrahim and Dyani’s historic record is an emblem of music in service to ideas beyond itself.