The inquest into Ernest Dipale’s death begins

The young activist died in the cells at apartheid police station John Vorster Square six months after Neil Aggett in 1982. This follow-on inquest may finally unravel the circumstances of his detent…

Author:

18 February 2021

Testimony in the reopened inquest into the 1982 death of activist Neil Aggett has ended, with closing arguments to be delivered to Judge MA Makume in March. But as the result of a December decision by National Director of Public Prosecutions Shamila Batohi, the judge is now required to hear evidence in another matter, that of the death of 21-year-old Ernest Dipale.

Dipale was found hanged in his cell at the John Vorster Square police station in August 1982, six months after Aggett. Because some of the former Security Branch officers who were involved in Aggett’s detention and interrogation are implicated in the Dipale matter, and because the deaths occurred within a short space of time and at the same location, Batohi instructed that the Dipale inquest be heard in conjunction with the Aggett matter.

Related article:

Testimony began with evidence from Dipale’s family and friends, to paint a picture of his life and political activities before his death. Long-term harassment of the Dipale family by members of the former apartheid security forces has a timeline that is difficult to unravel and includes the involvement of two of South Africa’s most infamous former askaris and assassins. Butana Almond Nofomela’s death-row confession in 1989 of his Vlakplaas activities blew the lid on the existence of apartheid death squads. And fellow Vlakplaas operative Joe Mamasela’s confessions helped expose the nefarious actions of his former commanders Dirk Coetzee and Eugene de Kock.

How Dipale came into contact with these apartheid killers is a matter of some contention. But based on snippets of evidence given at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and an examination of the file kept on him by the former security police, it is possible to establish some facts that will no doubt be covered in the coming weeks.

It is hoped that this time around, the findings of an all too perfunctory, indifferent and unsatisfactory inquest into Dipale’s death in 1983 – ruling his death a suicide for which no one was to blame – will be overturned.

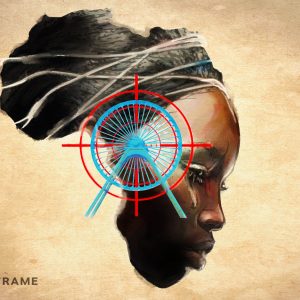

Security police spy

Ernest Moabi Dipale was born on 20 September 1960 and grew up in his family home in Dube, Soweto. His mother had been politically active in the 1950s and participated in the Women’s March in 1956 and his father was also involved in ANC politics. His older sister Joyce had become politically active during the Soweto protests of 1976 and was arrested and detained by the security police for 500 days in 1976-1977, during which time she endured brutal torture that included electric shock, beatings and humiliation. Dipale was a teenager when his sister returned home after her detention and left for exile in Botswana, where she and her husband Roller Masinga offered sanctuary to ANC activists escaping South Africa.

According to a statement, which he allegedly made to police while in detention on 7 August 1982, one day before his death, Dipale became politically active in the early 1980s during trips to visit his sister in Gaborone. There he met several ANC activists, including a young supposed ANC member and activist named Joseph Mamasela, who would often transport Dipale’s sisters to school in Gaborone. It is now known that Mamesela was a spy for the security police and that his work for the apartheid state would later lead him to Vlakplaas, where he would become one of the unit’s most ruthless and enthusiastic killers.

Dipale, who had dropped out of high school and studied to become a motor mechanic, repaired cars at a garage in Soweto. He was also a messenger for his sister and the ANC in Botswana, helping liaise between exiles in that country and members in Soweto.

According to Nofomela’s application for amnesty to the TRC, he and Mamasela were instructed by their security branch commanders in October 1981 to kidnap Dipale from his home in Soweto. They were told to deliver him to be interrogated by security branch officers Captain Jan Coetzee and Lieutenant Koos Vermeulen at a farm near Zeerust in North West province.

There, Dipale was interrogated about the whereabouts of his sister. Vermeulen, Nofomela and Mamesela assaulted him with such violence that he lost consciousness. Nofomela said he was unclear if Dipale had revealed any information in regard to his sister and did not know what had happened to him after this interrogation. The TRC granted him amnesty for his role in Dipale’s kidnapping and assault.

Covert operation

Dipale was arrested and detained at John Vorster Square a month later, on 5 November, and held there until 29 January 1982, according to security police records. He was in detention there at the same time as Aggett and other activists in the Barbara Hogan investigation, but he did not have any direct political involvement with them.

He made a complaint of assault to the inspector of detainees during this time. He alleged that during interrogation on 23 November 1981, he was “taken out at night and electric shocked”. Dipale said he “would like to see a doctor” and complained of “pain below the stomach”. A police affidavit included in his security file says Dipale’s complaints of assault were investigated and found to be “baseless”.

Related article:

On the night of 26 November 1981, while her brother was in detention, Joyce Dipale opened the door of her house in Gabarone and was grabbed and shot at point-blank range by Mamasela. He, Coetzee, Nofomela and others were there to raid the house and kill everyone they found in a carefully planned covert operation.

Joyce was shot in the neck but survived, making an affidavit to the Botswana police that she recognised her attacker as Mamasela, a man she knew from ANC structures in Botswana. Dipale suffered a stroke as a result of the attack, which left her with severe aphasia that has significantly affected her ability to speak since. She never saw her brother alive again and was in Zambia, recuperating from her injuries when she heard the news of his death.

Related article:

It is unclear if the attack on Joyce, coming only a month after her brother’s abduction and torture, was the result of information he may have given his interrogators. However, whether or not Dipale had been broken to such an extent that he may have given up names or other information, the raid and attempted murder of his sister did not end the security police’s interest in him. Almost seven months after his release from John Vorster Square, on the night of 5 August 1982, Dipale and his friend Oupa Koapeng were driving in Soweto when they were chased by a car and shot at by the driver.

They escaped and reported the incident at the Meadowlands police station. It was later revealed that the driver of that car was Mamesela, who claimed during testimony before the Harms Commission that he had “tried to apprehend him [Dipale] … gave chase, and in the process fired four shots from my revolver at the vehicle, but Dipale and his companion managed to escape. I reported the occurrence and a description of the vehicle … and Dipale was subsequently apprehended and detained by other members of the South African Police. I was later informed that Dipale had committed suicide by hanging himself in the cell in which he was detained.”

Mamasela testified before the TRC but refused to apply for amnesty for his involvement in any of the murders or operations he allegedly took part in, including Dipale’s kidnapping and the raid on Joyce Dipale’s house in Gaborone.

Criticism and outcry

Ernest Dipale was arrested on 6 August 1982. He spent the following day allegedly making a statement to the police,which was presented before a magistrate, according to officer statements in his Security Branch file. He also led the police to various locations in Soweto and elsewhere, where he pointed out the locations of dead letter boxes and other places of interest relating to his political activities.

One of the officers who accompanied Dipale and was part of his interrogation was Nicolaas Deetlefs, who testified last year of his involvement in interrogating Aggett and has been accused by former detainees including Hogan and Carl Niehaus of assault and intimidation. Deetleefs denies those charges and has said he had no involvement in the deaths of either Aggett or Dipale. Dipale was scheduled to appear in court on 8 August 1982 but he was found hanged in his cell that morning, a few weeks before his 22nd birthday.

Related article:

Coming so soon after the much publicised death of Aggett, there was much public criticism of the government and outcry from opposition parties following Dipale’s death. Former minister of law and order Louis le Grange claimed that Dipale had been held in a “virtually suicide-proof cell” at John Vorster, which had been modified at the cost of R43 000. He told reporters in response to criticism of the treatment of detainees that he did not “think one would get much information from someone being detained in a five-star hotel”. It was a callous quip that earned him and the government open disapproval from opposition party members.

As a result of the public condemnation of the government’s detainee policies, the security police watched Dipale’s funeral carefully. It was subject to severe restrictions that banned political speeches and protest songs, and strictly controlled the funeral procession route.

Dark corners of history

The immediate result of Dipale’s death was Le Grange implementing tighter measures to monitor political detainees, including the installation in 1984 of CCTV cameras in the cells at John Vorster Square in spite of widespread criticism of this policy and its implications for the privacy of detainees. Dipale’s death also led to the removal of Major Arthur “Benoni” Cronwright from his position as head of the security police at the station, under whose watch a number of deaths occurred.

The negative publicity for the apartheid state that resulted from the deaths of Aggett and Dipale contributed to the new, more sinister use of covert death squads such as Vlakplaas for the elimination of anti-apartheid activists. These were hidden from the glare of public scrutiny and worked their evil far from urban centres.

It remains to be seen if unravelling the circumstances of Dipale’s death and his prior political activities will help shed light on what happened to him in the cells of John Vorster Square during his final days of detention and interrogation in August 1982. What is clear is that his story is one that has many strands and reaches into some dark corners of South African history, and that his death has cast long-reaching shadows on his family’s lives.

Mamesela and Nofomela have indicated that should they be subpoenaed, they will testify before Makume. But whether they will offer some hope to the Dipale family of finally obtaining long-awaited answers and a possibility for closure is uncertain and remains subject to the whims of two men whose previous history is fuelled by self-preservation and self-justification.

The Ernest Dipale inquest continues. Proceedings are live streamed daily on the Foundation for Human Rights’ Facebook page.