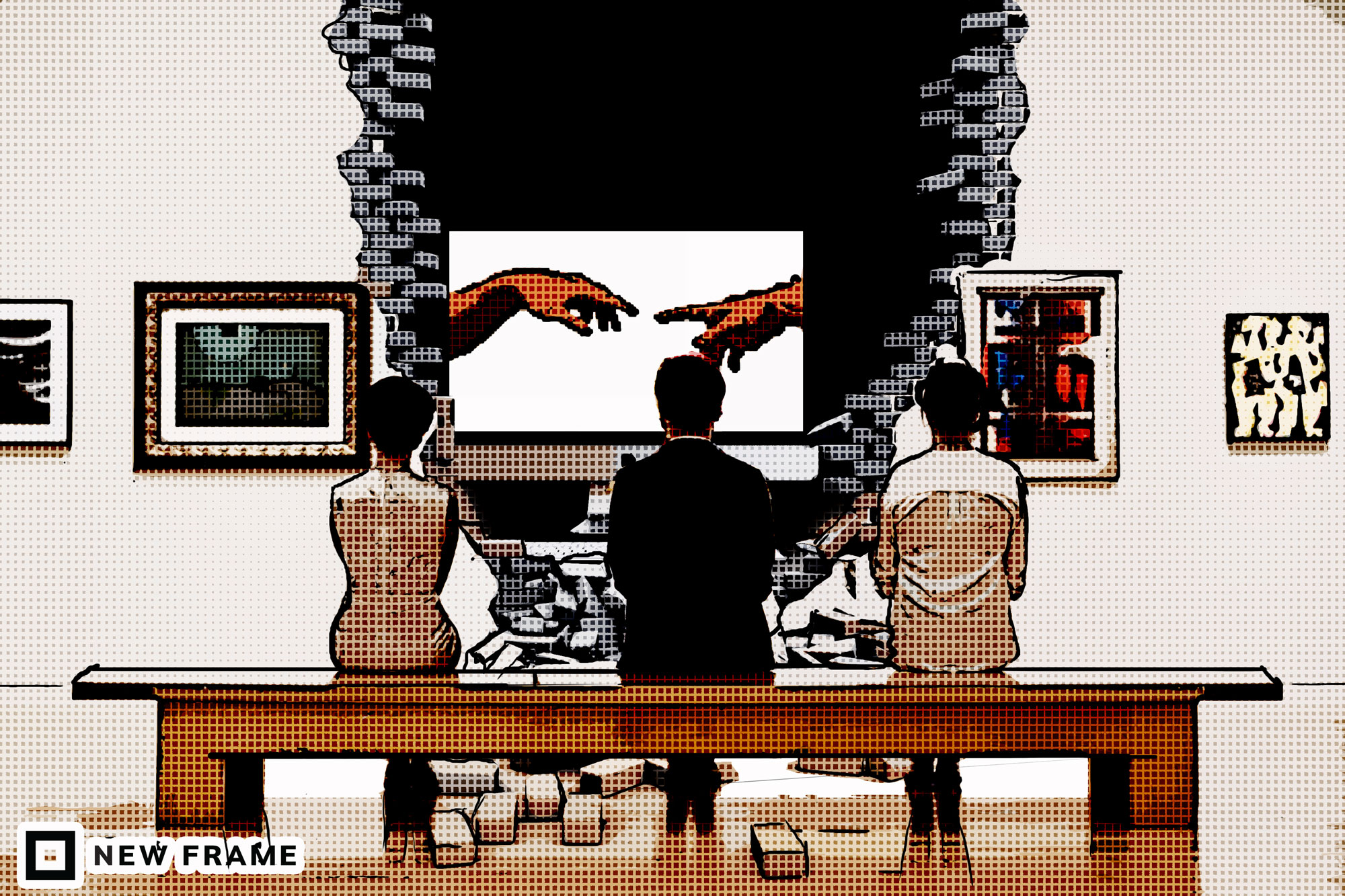

The new artistic age of self-representation

A necessary reprieve from the market logic of established galleries has been helped along by the Covid-19 pandemic, which has opened online doors for artists and collectors alike.

Author:

31 August 2020

When 36-year-old business analyst Thulisile Nhlapo arrived at a leading Johannesburg art gallery shortly before lockdown to buy art, she was surprised to find herself ignored. “It was as if the gallery staff looked right through me,” she recalled in a recent interview. Left to wander the gallery as if she were a casual visitor, she kept her money and spent it instead on two artworks she found on Instagram.

Since then she has bought a further two artworks through Instagram, and she doesn’t plan on returning to the gallery. “Why should I put myself through that?” she said. “Those spaces are not for me. They don’t recognise me because I don’t look like ‘a collector’ and I’m not spending huge amounts of money.”

Collectors like Nhlapo, whose buying of art unfolds by the flick of a thumb rather than by strolls through silent white cubes, are one side of a dramatically changing creative economy that is challenging traditional gallery representation, a relationship according to which an art gallery commercially and critically mediates an artist’s work. Frustrated, excluded and intimidated by the entrenched elitism of the gallery system, these collectors – many of them young – take to social media and other online platforms to connect with artists and buy work from them directly.

Related article:

Artists, the other side of this economy, are adapting to this shifting landscape as well. They are increasingly independent of galleries and dealers, and their growing prospects online might eventually make the traditional commercial gallery model redundant.

Lunga Ntila, who uses Instagram as a sales platform for her artworks, says that while gallery representation “could be beneficial”, it is not essential to an artist’s career. “I personally enjoy the independence I have currently. It allows me freedom to show my work with whoever I want and it gives me artistic freedom, too.”

Artists doing it for themselves

Artist and curator Banele Khoza shares Ntila’s view. For him, gallery representation is superfluous to the profile he’s established under his own steam. Previously associated with three different galleries, including Cape Town’s recently closed SMITH Studio, Khoza struck out on his own in 2018 and opened a private exhibition space in Braamfontein’s Juta Street. He hasn’t looked back.

“To be honest, I have not encountered great challenges as an independent artist,” he said. “Going into the gallery system, I was already in the act of developing an audience. I was already sharp in my administration.”

Called BKhz, Khoza’s Braamfontein space offers curated exhibition opportunities to emerging artists who are, in many cases, on the periphery of the mainstream art market.

Related article:

“BKhz was informed by the lack of opportunities available to my peers,” Khoza said. “While in varsity in my second year, I was already getting invites to showcase my work and seeing it find refuge in collectors’ homes. It wasn’t the same for the artists I was immediately sharing space with, whom I believe were more talented than I was, such as Tatenda Chidora, Nhlanhla Nhlapo and Keneilwe Mokoena.”

Although he runs a physical space, Khoza has embraced the possibilities offered by technology, creating virtual reality “recordings” of each of the exhibitions that BKhz hosts. Gallery or not, it is the first space in Africa to embark on this form of dissemination, potentially reaching audiences who, whether from necessity or choice, engage with art primarily online.

Navigating online pathways

Khoza has been described as a gallerist, but he sees his role as more nuanced than this. “I am more of a bridge than a gallerist,” he said, implying that he facilitates connections between artists and collectors, or bridges a gap between these constituencies.

Navigating this gap effectively, and cutting through the noise of social media, seem to be a significant challenge for the new wave of independent artists. As Ntila explained: “The biggest challenge [in not having gallery representation] would be getting your work to collectors. Social media platforms are amazing in regards to spreading the word on who you are and what you do, but sometimes it doesn’t yield results.”

Recognising the need for better “results”, and for more ways for independent African artists to connect with local and international collectors, Latitudes Art Fair recently launched the web platform Latitudes Online, a curated online venue for artists from Africa to present and sell their own work. Latitudes Online emerged out of the art fair, a newcomer to the global art fair scene, which had to cancel its second edition, originally scheduled to take place in Johannesburg in September 2020, because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Related article:

Latitudes opted not to stage a timed online fair to take the place of the physical edition, a move that many major international fairs have made this year, but rather to translate the fair concept into a permanent online marketplace. The fair’s co-director, Lucy MacGarry, sees this transition as in step with an epochal shift in the art world: “The change due to the pandemic has been incredible and so fast-paced, but it’s kind of forced the whole industry online. I don’t see that reversing.”

Latitudes is disrupting the art market’s conventional channels by acting as an intermediary between independent artists and collectors. This is unheard of for an art fair, which traditionally exists as a showcase for galleries rather than artists, much like trade fairs function as platforms for vendors. Galleries balk at the idea of independent artists being shown at art fairs because it undermines their position as middlemen. On Latitudes Online, galleries and independent artists vie for collectors’ attention equally.

For MacGarry, this levelling promises greater transparency in the art market. “I’ve always thought there was a great demand for a platform where you could view the entire art ecosystem transparently. Latitudes Online comes out of that need for transparency,” she said.

The challenges of independence

But for many artists, independence is not so much a choice as a default. The financial buffer, marketing infrastructure and administrative support that come with gallery representation do not yet have compelling alternatives in the world of self-representation.

Interdisciplinary artist Reshma Chhiba, who has been independent since her gallery, Art Extra, closed in 2010, has a more seasoned understanding of the strain that comes with independence.

“It’s a really tough space at the moment for artists who are independent and self-funded,” she said. “We have very few spaces we can access. It’s difficult to find exhibition spaces you can just get into. You’re writing so many applications and getting so many rejection letters. And even if curators want to show your work, they often don’t know how to access you because you’re not represented by a gallery.”

Chhiba’s artistic practice, which traverses photography, painting, sculpture and Indian classical dance, does not fit neatly into the often limiting commercial imperatives of traditional galleries. “I would sign with a gallery who would allow me room not to have to play to commercial interests,” she said. But no such gallery seems yet to exist.

As part of the market, commercial art galleries need “stock” to sell and, in turn, artists to produce in stock-like quantities, which factors into their consideration of the artists they represent. That said, productivity is only one half of a summarily baffling equation.

Related article:

Just as collectors like Nhlapo are marginalised and excluded, artists who don’t have access to the art world’s value-conferring and privileged structures, such as tertiary education (at the “right” institutions), professional networks and artists’ residencies, are often seen by top-tier galleries as sources of a less valuable or unsellable “product”, according to their market logic. The problem with this system is that galleries hold all the cards.

This is why attempts to circumnavigate the gallery system are potentially so disruptive but also so precarious. Chhiba, who is unyielding in her commitment to a slow and steady practice, is philosophical about her position, an approach that may be necessary when opportunities are few and far between.

Like Hippocrates, the ancient Greek physician, she says that though life may be short – perhaps too short to see galleries finally stripped of their roles as gatekeepers – art is long. “Even if in 100 years’ time someone picks up your work and it makes a difference to them, then you’ve done your job,” said Chhiba.