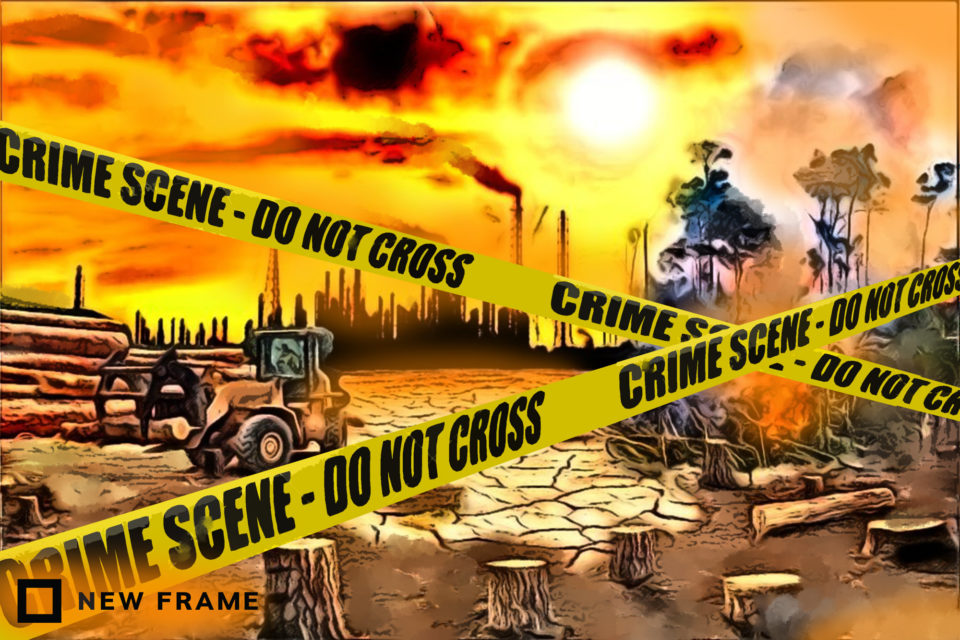

The push to make ecocide a punishable crime

Law experts have unveiled a formal definition of the term in an effort to make the destruction of the planet prosecutable by the International Criminal Court. But will it gain enough traction?

Author:

27 July 2021

Coinciding with the 75th anniversary of the Nuremberg war trials and the first uttering of the term “genocide”, momentum is growing to add a new term to the global law lexicon: ecocide.

Combining the Greek “oikos” (house, home, habitat, environment) with the Latin “cide”, meaning to kill, the word ecocide draws on the approach taken by Polish jurist Rafael Lemkin, who introduced the word “genocide” in his 1944 book on Nazi atrocities, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe.

Ecocide, referring to humans’ wanton, deliberate and large-scale destruction of the Earth and the natural world, popped up nearly a quarter of a century later when the American army invaded Vietnam and sprayed about 31 000km² of crops and forest cover with Agent Orange, a cocktail of toxic chemicals that poisoned both people and the environment.

Ironically, the term ecocide was birthed in 1970 by the American plant biologist Arthur Galston, whose early student studies into the defoliant effect of plant hormones ultimately gave rise to the military invention of Agent Orange. Dismayed by the perversion of his scientific endeavours for use in biological warfare, Galston later used the word to describe the environmental harms inflicted by both Agent Orange and “Rome plows”, large military bulldozers that flattened the jungle vegetation physically.

“I used to think that one could avoid involvement in the antisocial consequences of science simply by not working on any project that might be turned to evil or destructive ends,” he opined. “I have learned that things are not all that simple, and that almost any scientific finding can be perverted or twisted under appropriate societal pressures.”

Galston visited Vietnam later to view the damage first-hand and also began to lobby scientific colleagues and the United States government to stop using Agent Orange, which president Richard Nixon finally banned in 1971.

Slow progress

By then, other voices had joined the campaign to define and combat ecocide. Swedish prime minister Olof Palme spoke explicitly about ecocide in his opening speech to the United Nations Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment in 1972. The conference drew fresh attention to multiple environmental crises on the global stage and prime minister Indira Gandhi from India and the leader of the Chinese delegation, Tang Ke, also denounced the Vietnam War on human and environmental grounds. There was no reference to ecocide in the official outcome document of the conference, however.

But the Folkets Forum (People’s Forum), which ran parallel to the official conference, established a working group on genocide and ecocide that included Princeton University law professor Richard A Falk. In 1973, Falk published the first formal proposal to establish an international convention on the crime of ecocide under the aegis of the UN system.

Recalling the US military’s attempts to turn Indochina “into a sea of fire and compel peasants to flee their ancestral homes” through systematically destroying their environment, Falk raised concerns about it trying to modify weather patterns by spraying silver iodide over clouds in an attempt to induce heavy rainfall that would turn the Viet Cong’s famous Ho Chi Minh trail into an impassable mud bath.

Noting the power and obstructive capability of the US and other superpowers to block discussion on the issue of environmental crimes, Falk commented that the world was slowly waking up to the fact that humanity’s “normal activities” in peacetime were also destroying the ecological basis of life on the planet. There was, therefore, a need to develop new laws that address these dangers. A popular movement committed to the defence of the planet against ecological destruction was also needed.

This pressure to declare ecocide an international crime continued for several decades and remained on the agenda of the UN’s International Law Commission until 1996, when it inexplicably “disappeared”, according to a paper published in 2012 by the University of London’s Ecocide Project.

Nevertheless, the idea refused to fade away, and more recently the concept of declaring ecocide a global crime has been supported by Catholic Church leader Pope Francis and several member states of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Most recently it has gained further traction through the Stop Ecocide Foundation, co-founded in 2017 by late Scottish barrister Polly Higgins and its current executive director, Jojo Mehta.

Enforcing accountability

Now an independent expert panel has published a new legal definition of ecocide with the intention of making it the fifth international crime that can be prosecuted at the ICC in The Hague. Co-chaired by Dior Fall Sow, a former Senegalese jurist and legal scholar, and Philippe Sands, a professor of law at University College London, the 12-member panel is urging governments to consider adopting the proposal as an amendment to the Rome Statute of the ICC.

Sands said it could conceivably be used to hold corporate and state leaders and officials accountable for acts of “wanton” and “long-term” damage to the Earth’s life-support systems. Potentially, this could include the future construction of new coal-fired power stations by major industrial nations, large-scale deforestation and major oil spills and pollution.

The panel hopes its proposal will capture sufficient public and political support to catalyse governments into amending the Rome Statute, which currently has jurisdiction to prosecute four crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression.

Related podcast:

The “ecocide panel”, commissioned by the Stop Ecocide Foundation with support from Swedish parliamentarians, spent six months crafting a legal definition for adoption by a two-thirds majority of signatories to the Rome Statute, or 82 of the 123 state signatories, which currently exclude the US, China and Russia. The panel, which includes a former ICC judge and prosecutor, has no international legal status, but it is nevertheless pushing to move its proposal from a mere “catchy phrase” to a legally enforceable global instrument if sufficient political support can be mustered.

Speaking on 22 June at the global launch of the panel’s new legal definition, Sands said he was no longer starry-eyed about the power of international criminal law. “The mere adoption of a [legal] text does not stop conflict … But it causes us to think about the world differently – and the possibility that the law can be used to protect the environment.”

In terms of the proposed ICC statute, the only people who can be targeted for prosecution are individuals and not states, fossil fuel corporations or non-governmental organisations. Nevertheless, said Sands, actions could still be brought against individuals associated with such bodies. “My own sense is that we are now at a point where support [for this initiative] is widespread and growing.”

Careful approach

Just as war criminal Hermann Göring was held responsible for the atrocities of the Nazi regime during his trial and subsequent conviction at Nuremberg, so too could a corporate chief executive or a minister of finance be caught in the new legal net of ecocide.

Sands acknowledged that the panel’s proposals would not be ambitious enough in the eyes of many concerned observers. The panel did not want ICC member countries to “throw their arms up in horror” and run away from supporting the new proposal, which had been carefully crafted to strike a balance between setting the bar too high or too low, to the point where it was “basically useless”.

Ultimately, he said, it would depend on whether there is sufficient political will among at least 82 member states to ratify an amendment to the Rome Statute.

But if the snail’s pace of multilateral inaction to resolve the global climate change crisis is anything to go by, there could still be a mountain to climb. After all, politicians have been talking officially about the need to deal with climate change for 42 years.

The peacetime juggernaut of ecocide has not stopped rolling during that time, but Fall Sow emphasised the need to simplify and popularise the concept of ecocide among ordinary people. “We must not give up,” she said.