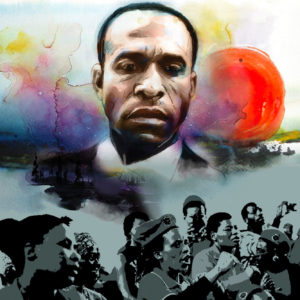

The slow Marikana

The scale and intensity of the repression against popular dissent in Durban is staggering. If left unchallenged it will, in time, arrive in the suburbs.

Author:

11 March 2022

This week, in a searing report from Nomfundo Xolo, New Frame reported on the murder of Ayanda Ngila at eKhenana Commune in Cato Manor, Durban. Ngila, a leader in the commune, had recently returned after a second unwarranted stint in prison, where he participated in a radical reading group studying texts by Paulo Freire, Frantz Fanon and others.

Durban is notorious for political violence within the ANC and against those who challenge its predatory rule from below. Ngila took his last breath a few steps from the Sifiso Ngcobo poultry project and the levelled area outside the Frantz Fanon School where, just over a year ago, residents performed a play about the assassination of Thuli Ndlovu.

Ndlovu, a leader in Abahlali baseMjondolo in KwaNdengezi, was assassinated in 2014. Unusually, two ANC councillors were convicted for her murder. Ngcobo, also a leader in the shack dwellers’ movement, was assassinated in Marianhill in 2018. More typically, no one has been arrested for his murder.

Related article:

At the large meetings held in the commune, in which members of the movement from across the city and sometimes other provinces have participated, speakers regularly list the names of the dead – as does a song composed by the Abahlali baseMjondolo Choir formed in the nearby eNkanini occupation. Land for living on has also been won here at the cost of death. Nqobile Nzuza was 17 when the police murdered her on a road near eNkanini, with a shot fired from behind at close range, in 2013. Nkululeko Gwala was assassinated on his way home from watching a football game in a tavern that same year.

The politics of Abahlali baseMjondolo has come to be saturated with an awareness of death. In meetings it is common to hear women – often mothers trying to find a space in the world for their children – say with resignation rather than defiance, umhlaba noma ukufa (land or death). A number of land occupations and branches in the movement are named for the dead.

Forging a commune from an occupation

The land that became eKhenana was first occupied in 2017 in, as often happens, a sudden, rushed and disorganised scrabble. Later on, as it began to take on an organised form, clear lines of division emerged between those who wished to ensure that land was not bought and sold and shacks not rented, and those who wished to profit from the occupation. Inevitably, some in the latter group made common cause with the local ANC. As eKhenana moved towards becoming a commune, combining democratic self-management with collective production in the form of small but well-run urban farming projects, including poultry and vegetables, it became a key site in national and to some degree international nodes of organised dissent.

Related article:

The first seeds for the farming project came from the movement of the landless in Brazil, the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra. Classes have been run in the Frantz Fanon School on everything from Fanon to the Communist Manifesto, with students coming from the movement and other organisations across the country, sometimes the region. Retired Anglican Bishop Rubin Phillip has been a regular presence and there have been visitors from many parts of the world. In recent years, the large rallies held at eKhenana have begun with the singing of The Internationale, the communist anthem composed by Eugène Pottier, a participant in the Paris Commune of 1871.

The commune is increasingly becoming a central idea, and sometimes practice, in the best organised struggles across the Global South, in cities and in the countryside. For many, the vision for the future of struggles outside the workplace is allied movements of linked communes committed to building democratic counter-power from below.

Relentless repression

But in Durban, not unlike some parts of Latin America, organised dissent – even when it takes the form of non-violent attempts at building some autonomy from the state, the party and capital rather than engaging in direct confrontation – is met with ruthless repression. The scale and intensity of this repression is staggering.

eKhenana has endured so many armed, violent and unlawful attempts at eviction at the hands of the municipality that it started to become difficult to keep a precise count when the number started to climb towards 30. Escalating violence and other forms of repression marked these attempts at eviction. The police arrested and detained 24 women in November 2019. At the same time, three residents were admitted to hospital after suffering serious injuries as a result of violence at the hands of the police and the eThekwini municipality’s anti-land invasion unit. One had been shot in the testicles at point-blank range with a rubber bullet.

When the high court issued an interdict against unlawful evictions in April 2020, a senior municipal official went straight to the occupation where witnesses said he fired live ammunition at residents, injuring one person. As is common in Durban, the municipality simply ignored the court and continued to evict.

Related podcast:

Not one of the more than 40 arrests of eKhenana residents has resulted in a trial, let alone a conviction, but arrests do enable periods of imprisonment when bail is denied. Ngila had spent six months in prison on charges that were later thrown out of court, and was then promptly rearrested on a new charge after his release. This time he spent a shade under six weeks in prison before being granted bail. When Maphiwe Gasela, who had also spent six months in prison, was bailed out after her first arrest, her house was burnt down, after which she was also rearrested.

The local police station regularly turns residents away when they try to open cases against ANC members. The residents say a local ANC leader openly directs the police to arrest activists. New Frame reporters have seen this man walking in and out of the office of the chief magistrate when Abahlali baseMjondolo members appear in court. The local police have certainly been captured by the local ANC. Many think the same is true of the criminal justice system more broadly, including the prosecuting authority.

Elite indifference

eKhenana residents haven’t only sustained their hold on the land while under attack from the municipality, the police and the local ANC. There is also a fourth force at play: the systemic indifference of the bulk of the elite public sphere, including much of the media and many of the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that have the temerity to refer to themselves, in a crudely anti-democratic posture, as “civil society”.

Next year marks the 50th anniversary of the Durban Moment. This refers to the period beginning in the late 1960s and coming to full flower in the early 1970s when the city became the centre of new and radically democratic ideas developed independently of the ANC and, after the Durban strikes of 1973, linked the university to workers’ struggles. Worker control became a key concept in organising on the factory floor and, after the formation of the United Democratic Front in Cape Town 10 years later, ideas of community control also became central to wider forms of popular struggle.

Many progressive university-credentialled intellectuals were attracted to these ideas and the agency of the oppressed – protagonism in the language of liberation theology – was understood as fundamental to any struggle for liberation. But these days, as Steven Friedman has often written in New Frame and elsewhere, elites generally understand politics as an intra-elite project, in terms of oligarchy rather than democracy.

This is the key reason the relentless violence directed at the residents of eKhenana, including during the hard Covid lockdown, is not a national scandal. Elitism is so entrenched, so naturalised that it has become central to the unreflective common sense of a whole sphere of society. For this reason it seems unlikely that the middle class and the elites ranged across the state, media, NGOs and the academy will be persuaded to recognise the full and equal humanity of impoverished Black people by the mobilisation of ethical arguments.

But they should be mindful of what Aimé Césaire, the Martinican theorist and one of the great poets of the last century, called the “boomerang effect of colonisation”. Césaire, writing about fascism in Europe, noted that what was done over there, to them, under colonialism would inevitably return to Europe. In Malcom X’s famous phrase, the chickens would come home to roost.

If the middle classes do not start to take the unspeakable repression being meted out to some of us seriously, it will in time come for all of us. What activists have long called the “slow Marikana” or “the politic of blood” will not continue to respect the boundaries of the suburbs. As we saw with the assassination of Babita Deokaran last year, the lines that once decisively marked out the spaces inhabited by those whose full humanity is assumed and those whose humanity is denied, and vandalised with impunity, are already becoming permeable.