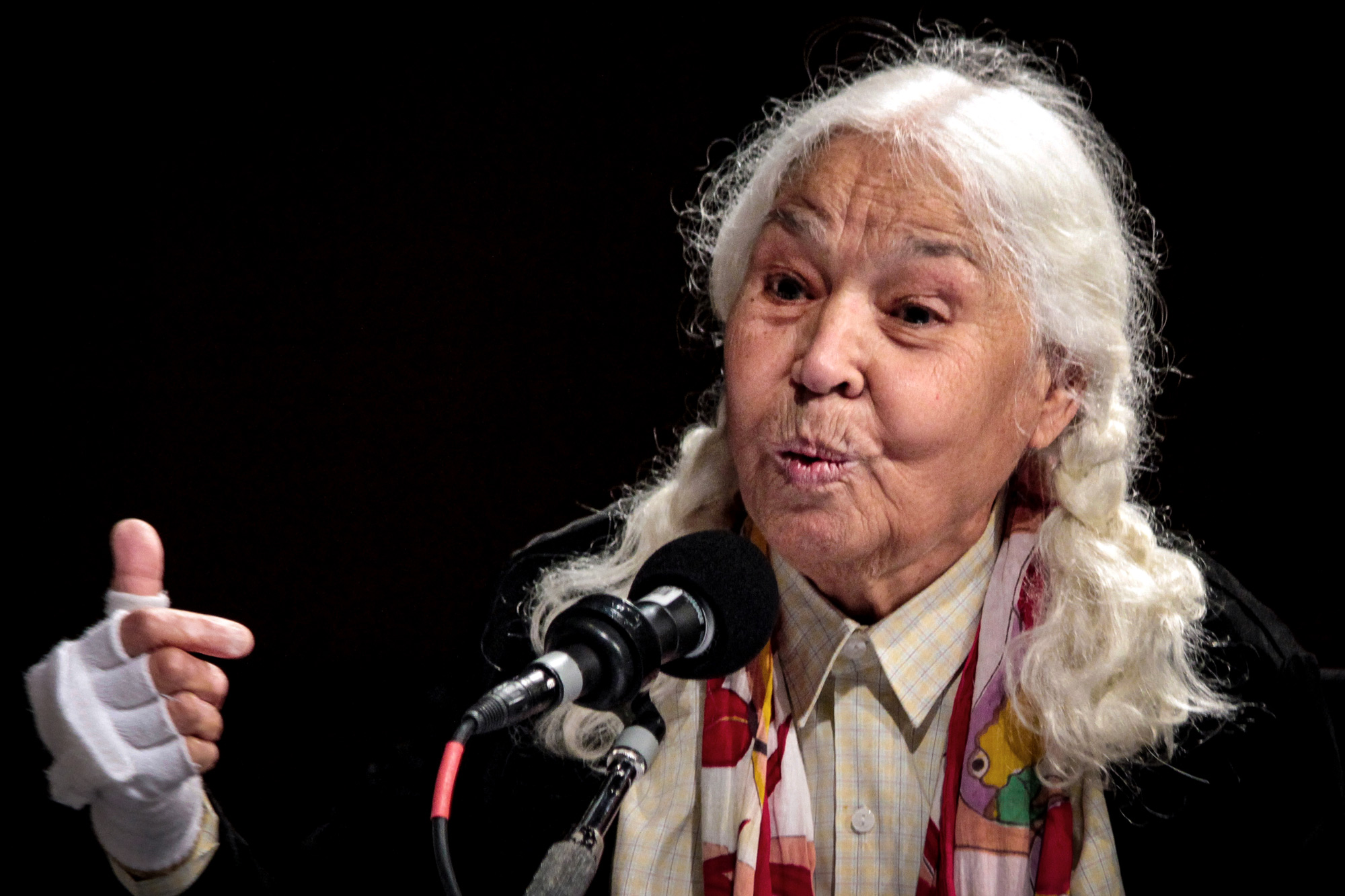

The socialist feminism of Nawal El Saadawi

It was not from the academy that El Saadawi’s views on feminism and socialism were forged but in her impoverished birthplace of Kafr Tahla, among women who never seemed to have a voice.

Author:

7 May 2021

The late Nawal El Saadawi had a deep desire to read and write as a child, but she did not have any books or paper. So she would buy packets of lib (pumpkin seeds) just to read the packaging. The renowned Egyptian writer, poet, activist and doctor would go on to pen more than 50 books in her lifetime.

Going to school was her freedom, particularly from the restrictions of the kitchen chores expected of a girl, and she started writing when she was just 13 years old. The twinned political commitments that shaped her life – to women’s rights and the working class – would go on to shape the arc of her career.

While an esteemed figure in recent years, she was born to an impoverished family in Kafr Tahla in 1931, a small rural village on the Nile River, to the north of Cairo. El Saadawi would go on to become the first medical doctor in Egypt to write about the trauma of female circumcision or female genital mutilation, campaigning against it and other violent patriarchal customs.

While she is known for being a staunch secularist and fierce critic of religion, it is important to highlight that her work is rooted in opposition to capitalism, militarism and imperialism.

Through her work, she expanded on the ways that the ruling classes use religion as an ideology of power. She continuously drew connecting lines between local, national and global struggles, ensuring that her advocacy extended beyond Egypt and reached across the Global South.

In a speech she gave at The City University of New York in the United States, she said: “When I came to the US previously, I’d find that people didn’t hold a good view of Egypt. They would say, ‘You receive so much US aid, why are people still so poor?’ The people didn’t get the aid, it went to US companies and to President [Hosni] Mubarak. And the aid made us into a US colony. Women can’t be liberated within a country that is a colony.”

For El Saadawi, it was fundamental to connect multiple sites of struggle, in ways that continue to resonate. In the same speech, she emphasised that “there’s a connection among neocolonialism, male domination and class domination. Some feminists talk only about patriarchy and don’t see poor women.”

In thinking deeply about what this means, El Saadawi focused not only on the material effects of domination but its impact on humanity, too. She said the “development” and “aid” that functioned as new forms of colonialism robbed people not only of their natural resources but also their dignity.

Her feminism continues to stand as a critique of the kinds of liberal feminisms that focus only on individual freedoms, with no thought to collective, connected liberties outside of capitalism’s clutches. She described herself as a socialist feminist, committed to the destruction of capitalism and the systems that rule the world, enforcing economic, political, physical and psychological power over the masses.

In The Hidden Face of Eve, she wrote about how capitalist production does not consider people’s needs, but only what yields profits. Importantly, she focused attention on the ways that most commodities that are marketed to women are out of reach for the majority. “Is it possible to contend, for example, the millions of women who toil in the fields and factories of the Arab countries require deodorants to remove the smell of sweat that never dries?”

A personal politics

El Saadawi’s rage and optimism were equally palpable. Her rage, resistance and revolt started when she was a young child.

She lived in a time and place where female genital mutilation was common. She also witnessed young girls, children really, being married off to old men. When mention of her marrying came up, she rebelled by staining her teeth black and pouring coffee on the men that came to meet her. However, her own traumatic experience of female genital mutilation is a wound that stayed with her indefinitely, she wrote.

After studying medicine and becoming a psychologist, she returned to the village to set up a practice to serve the people of her birth place, which had extremely limited medical services. Even though she attended university at a time of heightened leftist and anti-imperialist discourse and demonstrations in Egypt, it was going back home that truly awakened her political consciousness.

She observed that the physical and mental illnesses that many rural women contracted were caused by connected patriarchal and class oppression. On top of extreme poverty, women were treated as the property of men, often facing abuse. The more she read about the world, the more she realised that this was a global problem.

Her interpretation of socialism emerged from the injustices she witnessed throughout her life. In interviews, she repeatedly said that she was not a Marxist, because she read the theorist’s work and found flaws in it, including that he ignored gender injustice. For her, politics found meaning in how theorists lived their lives, with these being inseparable. She suggested that Marx was patriarchal, treating his own wife cruelly and not recognising his own child.

Related article:

El Saadawi’s feminism was not the lofty realm of university-trained intellectuals or mainstream cultures. She belonged, she said, “to the ‘historical socialist-feminists’, women who were inspired by our mothers and grandmothers and by the goddess Isis.

“When I was a child, my illiterate peasant grandmother led a women’s rebellion against the British and the men who ran her village. They were selling the villagers’ cotton crop to the king and Manchester [the British textile industry] for too little money. I remember visiting my grandparents; they were so poor that they never ate meat or eggs – even though they raised chickens to sell their meat and eggs to rich people in town. So we ‘historical socialist-feminists’ have feminist ancestors. We are against all forms of male domination, including the traditional family and including imperialism.”

Recalling the history of feminist organising in Egypt, El Saadawi wrote about the ways in which the work of upper-class feminists takes centre stage while the lives of impoverished and rural women are ignored.

In The Hidden Face of Eve, she wrote that “little has been said about the masses of poor women who rushed into the national struggle without counting the cost, and who lost their lives, whereas the lesser contributions of aristocratic women leaders have been noisily acclaimed and brought to the forefront”.

Consistent with her class critique, commenting on the Egyptian revolution of 2011 at the World Forum for Democracy in 2012, she spoke about how the elite (including herself, given her education) are seen as the “heroes” of the revolution even though they are 2% of the population. She insisted that the revolution could not have happened without the 98%, some of whom were killed or forgotten.

The double bind for Arab and Muslim feminists

Her work, however, was not without its critics.

South African feminist scholar Sa’diyya Shaikh says the feminist work of Muslim women is in a double bind. It has to contend with patriarchal structures and sexist interpretations of Islam, as well as Islamophobic and imperialist representations of Islam. “The fact that Muslim women resist both narratives while sometimes moving between their critiques is a consequence of the way in which they are situated within this larger minefield,” she wrote.

While El Saadawi gathered a movement of followers and like-minded feminists during her organising, some say the Western media and academia often overemphasise her influence in Egypt and the Arab world generally. Amal Amireh, a professor of postcolonial literature at George Mason University, says her fame in the West, as a representative of Arab women, cannot be taken out of context of stereotypes of Arab culture and Islam. As an Arab woman who is a transnational feminist and travels internationally, she was caught in the “double-bind” of which Shaikh speaks.

This context, for Amireh, “ends up rewriting both the writer and her texts according to scripted First World narratives about Arab women’s oppression.”

Additionally, her stance against veiling – including supporting France’s secularism and ban against the veil – was controversial and contrary to the position of many Islamic feminists. She criticised the work of Islamic feminists who advocated for religious freedom, the choice to veil and the oppressive and racist forms of Western laws targeting Muslim women. Amireh writes that much of the Western reception of Saadawi’s work “focuses on anti-Islamic sentiments while ignoring her strong anti-colonial, anti-imperial and anti-capitalist sentiments.”

El Saadawi addressed in recent years the biased way her work is represented in the West. “When I’m in the US, I’m always asked about religious fundamentalism, but when I connect it to neocolonialism, then what I say is censored. I am told to leave it out of my talks. And in a recent TV interview by Christiane Amanpour, what I said about neocolonialism was cut out. But the two things are opposite sides of the same coin.

“Why is there this revival of fundamentalism in the 21st century? Because religion survives and flourishes under repression. Islam, Judaism and Christianity are similar in treating women as inferior, in fearing outsiders, and in their racism and classism. In spite of religion’s defects, however, I believe in protecting religious freedom.”

In remembering El Saadawi, it is important to recall both the shifting and certain cadences of a life committed to connected struggles – and one that fundamentally linked feminism and socialism.