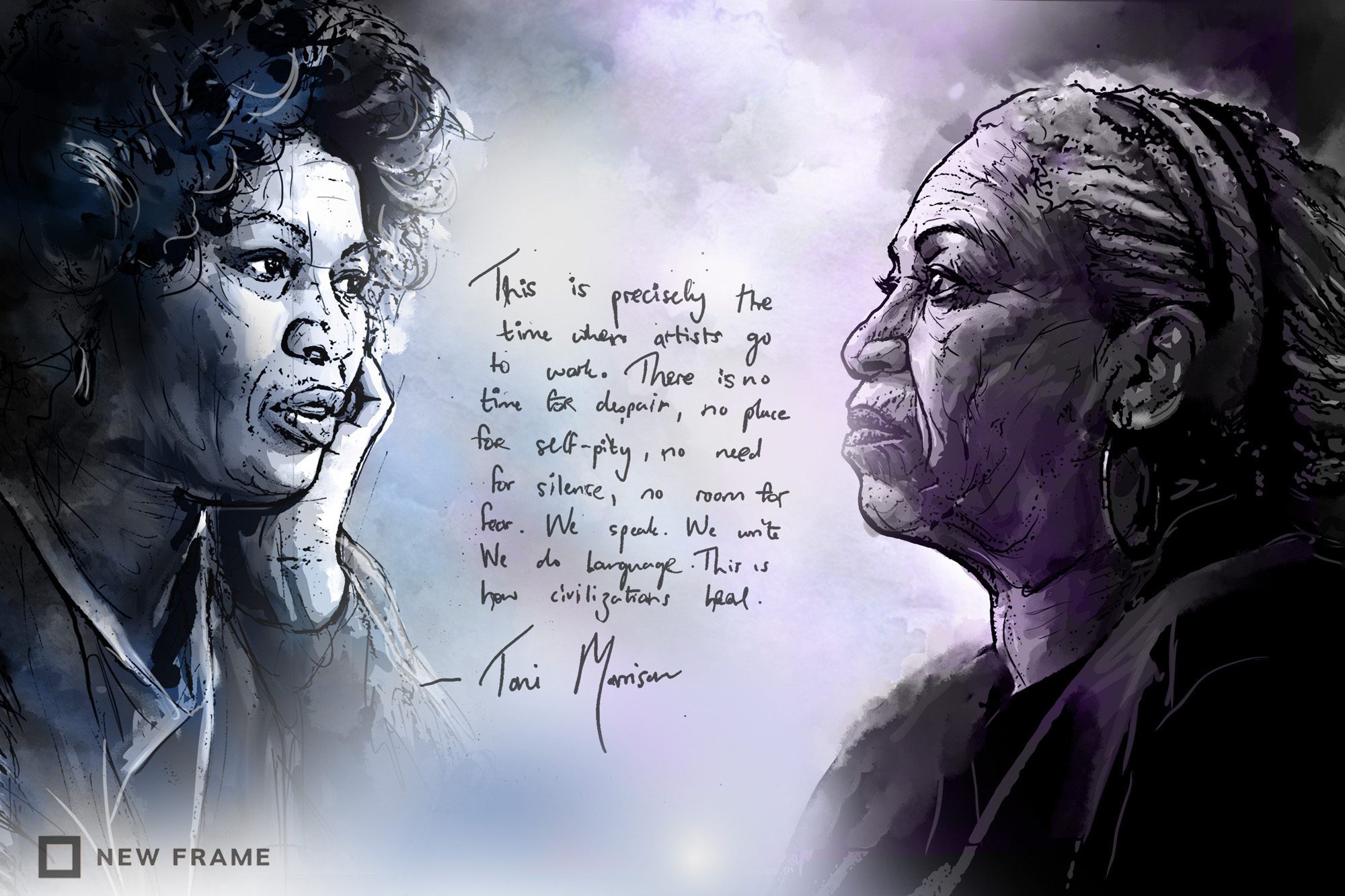

The words and worlds of Toni Morrison

For Nakhane, the Nobel Laureate’s books bring humanity to trauma and humour to the oppressed, representing, for the first time in high art, his family, his situation, his life.

Author:

13 August 2019

Each word, phrase and sentence from Toni Morrison is congested with meaning. There is a sense of move-and-you-will-miss-it. This was always the difficulty I had in reading Morrison. I would whoop in my room because a turn of phrase was so beautiful that I could not keep it internal – I would frighten my mother who would ask what was wrong, and I would reply, “No, don’t worry. I’m just reading a book.” I would meditate on what I knew were lessons to be gleaned. There was also joy, but above all else, there was fun in her writing.

Morrison once said: “The best art is political and you ought to make it unquestionably political and irrevocably beautiful at the same time.” And she did. From her work as a publisher right through to her interviews, there was always a lesson, there was always an interest in the human condition, and it was never dull.

The birth of a writer

I was 20 years old when I was introduced to Morrison’s work. It was the year I decided I wanted to be a writer. And so I made it my duty to read as many critically acclaimed novels of the 20th century as I could. In every list of the best appeared Beloved. With the little money I had, I went to the nearest second-hand bookshop and bought a copy.

The year before, the work of James Baldwin had done what Morrison’s work was about to do to me. As the Book of Revelations says: “The heavens had been rolled up like a scroll, and all the stars fell like withered leaves from the vine.” My relationship with the Bible is complicated. Where I once read each word as the voice of God, I now read it as I would any other book. But I often think of that Revelations verse when I am rendered powerless by a piece of art. There is something in that image, of the sky – of atmosphere – made tangible, made possible to hold and carry and roll and do away with that I love. I read it as a metaphor for a new beginning. What you thought was permanent has now been changed. And in this case, all the stars you knew, all the writers gleaming so white, have fallen and are now replaced by a person who looks like you.

Postapartheid 1990s education was not interested in teaching us about the history of black people unless it was adjacent to or the result of white principal characters. Most of the writers I knew were dead white guys. By the time I was looking into literature for myself, it was only natural for me to move on to living white guys and maybe the odd living white woman. I could never imagine that the way my family was set up, the way they spoke, the food they ate, how they loved could be worthy of writing, of being lifted to the highest of arts. I had not been shown it was even possible.

From the margins to the centre

Morrison gave me power. In all those books where black people were nothing but – these are her words – “some local colour”, she put me, my mother, my father in the foreground. She drew black characters who were full human beings. We were always in the fraying margins, not even clear enough to be seen. Her black pen brought us to the centre of the whitest page and wrote about us boldly. We were full of glory and failure, as cruel as we were kind, and as greedy as we were generous. I did not get finger-snapping sloganeering from her. What I received were truths that I – as an oppressed person – needed.

There is the dense dreamscape of what we can do with our trauma in Beloved. How the source of love can bud into flowers both lifegiving and lifetaking. She takes the scars on Sethe’s back and dreams them into a chokecherry tree. It’s as if she grabs us by the nape and shows us how we are hurt and the evidence and aftermath of that pain is ugly. But then gives us agency to take that pain and imagine it into something else, maybe even something beautiful.

In Sula, she weaves family and friendship into a complicated and complex tapestry of love that is not necessarily nice or flattering. The daughter who has overheard her mother say that as much as she loves her daughter, she does not like her, watches her mother burn and fall from a balcony.

Related article:

We see two possibilities of family in The Bluest Eye, one broken and one filled with joy and support. Pecola Breedlove shows us what trauma can do to people. Morrison lets us see how the emasculation of black men can make wounded people hurt other people. In this scenario, a father repeatedly abuses his daughter who is inculcated into the ideology of whiteness through her obsession with blue eyes. On the other end of the spectrum, we have Frieda and Claudia, two strong sisters who are full of self worth.

In Tar Baby, Morrison writes: “There were four of us in the room: me, my grandmother, and my great-grandmother. The oldest one intemperate, brimming with hard, scary wisdom. The youngest, me, a sponge.” I was this character. As soon as she entered my life, I became a sponge and her words filled every part of me. In my set at my latest performance at Meltdown Festival, her words filled London’s Southbank Centre as a bridge connecting songs. Text spoke to text.

Related article:

The first chapter anthropomorphises the Caribbean island of Haiti. By making it human, we see ourselves in it and perhaps become more compassionate towards the island that birthed the first slave rebellion, that was “unthinkable even as it happened”, in the words of historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot. No longer is it something for us to subdue and dominate, but something we should love. In two pages, with a tender and folkloric touch, she addresses issues that are in the news every day: climate change and the role of capitalism in it.

“I wanted to tell her a story,” Toni Morrison wrote in Tar Baby about her ailing grandmother, “to amuse her, maybe even cure her.”Are we cured? No, we are not. There is still so much work to be done. We may not be cured, but we are equipped. If we ever feel ambushed and snowed in by the cruelty of the world, we can pick up her books. If we ever feel despondent and are in need of a chuckle, we can pick up her books. She left behind a monumental but approachable legacy. We can, because she did. In death, she rests her life’s work in all of us.

Thank you for telling us stories, Mama Toni. We owe you everything.