Thulani Malinga focuses on next-gen boxers

The retired former world champion reminisces about his boxing career, what needs to be done to bring the sport back to its heights in South Africa and why he trains youngsters rather than pros.

Author:

12 December 2020

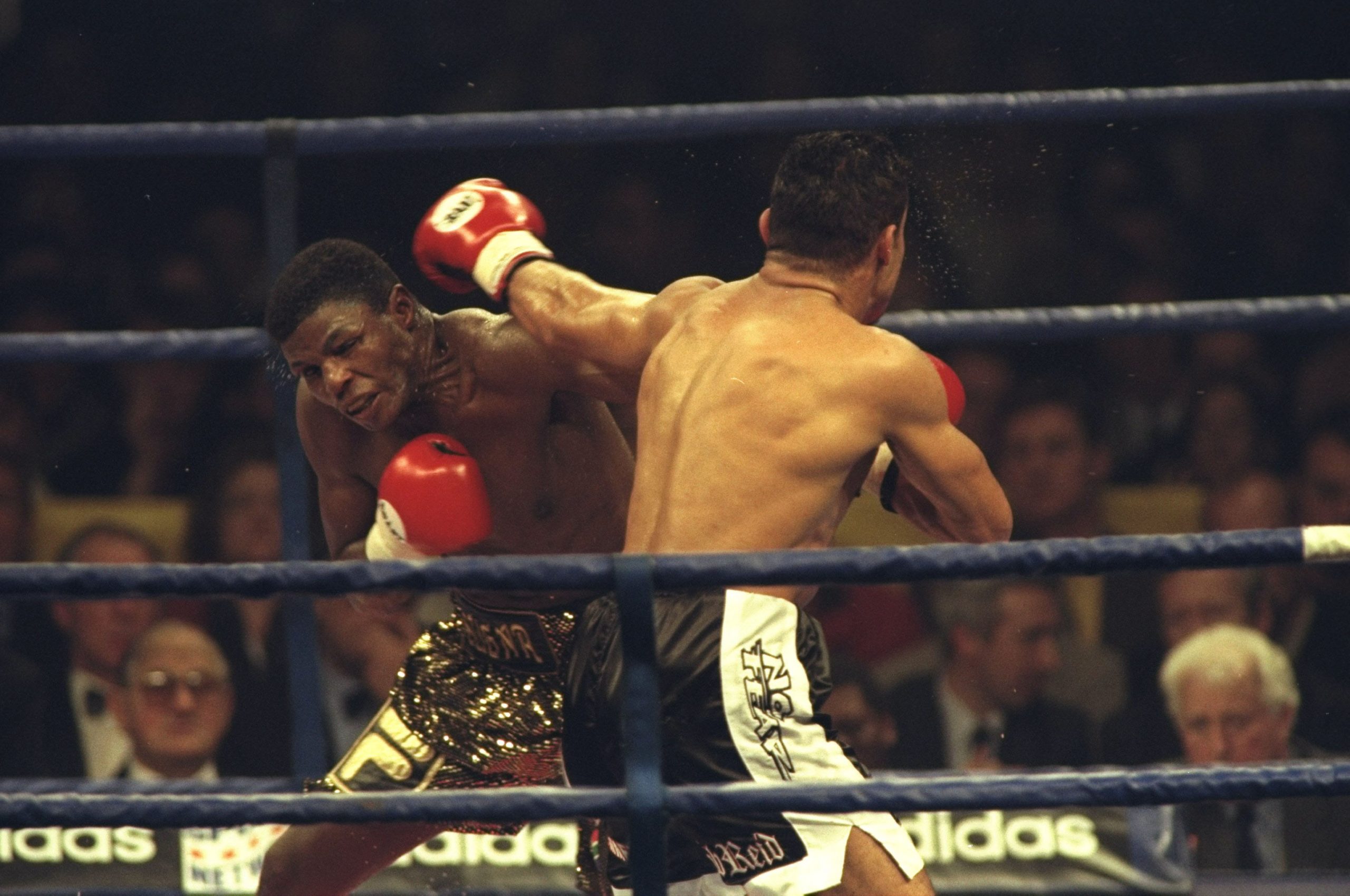

Thulani “Sugar Boy” Malinga became the country’s pride when, against all odds, he dethroned British superstar Nigel Benn in the United Kingdom in 1996 to become the super middleweight World Boxing Council (WBC) champion.

What made the victory even sweeter for the legendary pugilist was that, in being crowned WBC champion, Malinga became the first South African boxer to claim this title away from these shores. Later, Dingaan “The Rose of Soweto” Thobela would step up and scribble his name in the boxing history books by claiming the same belt from the UK’s Glen Catley in Brakpan in 2001.

That it has taken years for South Africa to produce another WBC champion paints a dim picture of the state of boxing in the country. Malinga’s current favourite boxer, Moruti Mthalane, is flying the country’s flag courtesy of him holding the International Boxing Federation (IBF) flyweight title.

Related article:

Malinga comes from a family of boxers. His nephew, Maxwell Malinga, was also a professional boxer.

Malinga was born in the Free State, grew up in Escourt and settled in Ladysmith. The 65-year-old’s first shot at a world title came in 1989, when he faced undefeated German IBF super middleweight champion Graciano Rocchigiani.

“In 1989, I received a telegram that I did not expect. I was about to fight with Rocchigiani for the IBF super middleweight belt in Germany. The telegram was from the first president of democratic South Africa, Nelson Mandela,” Malinga said.

“I was ecstatic to receive a telegram from a world-famous person. What was more surprising is how he found all the information about my hotel. In the telegram, he wrote that he was my No. 1 supporter and his favourite boxer in South Africa. He told me to win the world title for him.

“That telegram changed my perspective of life. It inspired me to always give my best in everything that I do. In that match, I fought hard. I did not want to disappoint him and myself, but unfortunately lost the fight by half a point. In the telegram he promised that if he eventually gets out of jail, he will make time to meet me. Indeed, he kept his promise and we met twice.

“When I had lunch with him in 1996, I saw that he had love for children,” continued Malinga. “He had a huge house around his yard where he houses orphans. He told me that if ever I needed something, I must come to him. When I retired, I wanted to do my organisation for developing boxers. I tried contacting him through his personal assistant but I could see that they were gatekeepers.

“What I really took from him is that in life you must persevere, even if things don’t go the way you want. He said I must always look at his life and how it turned out. He fought for freedom and South Africans are now free. There are so many things that I still wish to do for boxing in South Africa, even though things don’t go my way. I will not throw a towel, but I will try until my end of days on this Earth.”

Making history with his left hand

Malinga was confident when he took on Benn. He had more experience under his belt. “I went there knowing I will be a champion. I even dreamt about it,” Malinga said.

“By that time, I was ranked No. 1 by the WBC. I even told [promoter] Rodney Berman that I had a vision of my fight. He did not believe me. I told him that the date of the fight will be changed, and God has told me that he must give me more money. Berman did not understand what I was saying, but he eventually gave me the money I wanted even though I had signed the contract. What was amazing about my 1996 fight is that even Benn did not believe how he lost.

“Benn said that he did all he could, but he ended up losing. He was so humiliated that he even asked his girlfriend if she would still marry him after such humiliation. When I went there I was so fit, I trained differently, I used an axe to chop the wood to build my muscle. I only used my left hand to beat him, he came out with a round face.”

South African boxing is currently in a crisis. The sport that was once the most important in the country – giving Black South Africans many heroes during the fight against apartheid and in the first steps into a democratic society – is struggling when it comes to financial support and its viewership has dropped. This is the scenario Boxing South Africa acting chief executive Cindy Nkomo stepped into when she assumed her role in August.

Related article:

“I believe women need to be given a chance to run boxing in South Africa,” Malinga said. “I have no doubt that they will turn things around and do better than us men only if they are fully supported by other former boxers. The truth is women are better administrators than us, it is just that they are not given a chance to do so.

“South Africans need to adapt and be better athletes. In Europe, when you are an athlete, you are the boss. You pay your managers, not the other way around. In South African, managers become richer than athletes. We need better boxing promoters who are consistent. The only person who is a good promoter is Rodney Berman. Look how he has built the brand. He promoted me and younger boxers who came way after me. We really need to learn from him.

“The challenges in South African boxing are more than administration. The challenges stem from not having sponsors in boxing. We cannot run away from the fact that whites control sponsors. We had sponsors in boxing when the sport was dominated by white boxers. When the rise of Black boxers started, whites left with their sponsorship to rugby. Nonetheless, we cannot punish them for taking their money where they want to. We as Blacks need to build the culture of sponsoring sports. I believe Black South African businesses have grown in a way that they can be able to sponsor boxing again.”

The future

Malinga’s objective now is to play a role in producing the next generations of boxers. Malinga, who hung up his gloves in 2000, is part of a collective of retired boxers who are training youngsters between the ages of 12 and 18, with the aim of giving them important tips that no one shared with them when they were rising in the boxing ranks.

“I have no desire in training older people. I am passionate about boxing, I do it for the love of sport,” he said.

“I want to give them opportunities that I never had when it comes to developing a boxer. I was never developed as a boxer. Most of the things that I did was because of God-given talent. We are working with other former boxers in an organisation called South African Boxing Federation (Sabof) to nurture the raw talent in South Africa and take it to greater heights.

“We believe that by working together we can produce something magical and compete well in the Olympics. I believe I am a good teacher. I taught Nick Durandt boxing and he went on to become the best manager South Africa has ever had. The good thing about Sabof is that we allow amateurs to train with professionals so that they can gain skills and experience.”