Toil and trouble: Brazil’s history of land reform

The struggle for land in the country is inextricably tied to the struggle for agrarian reform that benefits those who work the land, and the recalibration of power relations in society.

Author:

23 April 2020

This is an excerpt from a Tricontinental dossier titled ‘Popular Agrarian Reform and Struggle for Land in Brazil’, published on 6 April 2020.

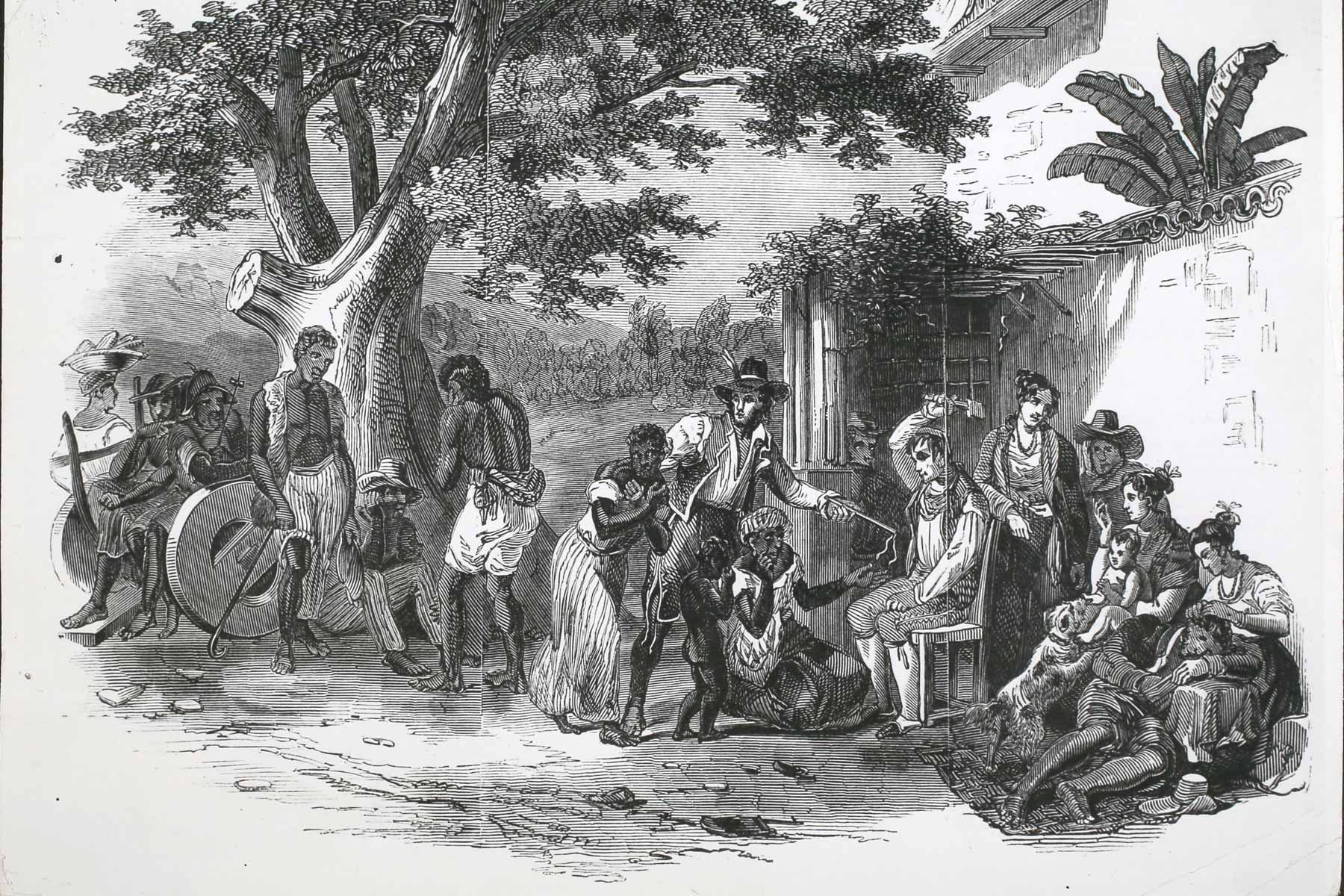

The land question is central to understanding political life and society in Brazil. The country has enormous landed estates, known as latifundios, which have their roots in the beginning of the Portuguese occupation of this part of South America at the start of the 16th century. The Portuguese seizure of this land and its conversion into large latifundios – together with the mono-cultivation of crops for export and the enslavement of human beings – established the roots of social inequality that persist to this day.

The most recent census in Brazil, undertaken in 2017, showed that this structure of land inequality has not only remained in place over the years, but that land concentration has increased. Roughly 1% of landowners control almost 50% of the land in rural Brazil. Half of all rural landowners have holdings that are less than 10ha (a soccer field is about one hectare), but these holdings account for barely 2% of the total land. In other words, most holdings are enormous and are held by a small minority – the landowning elite.

The inequality in land ownership illustrates the scale of the expropriation that capitalism has engendered over the past centuries, which has had political, economic, social and environmental consequences for Brazil’s development. Land relations, which are expressive of a social order, are fundamental to shaping Brazil’s inequality and its social potential. The idea of land encompasses not only territory, but also people, natural resources and control over them, and development in its broadest sense.

On top of the archaic and unproductive latifundios have emerged the agribusiness behemoths. No longer is the struggle for land in Brazil centred around the conflict over small parcels of land between the holders of latifundios and the poor peasants; it is now centred around the question of what Brazil’s agricultural model should be. The giant agribusiness firms not only dominate enormous stretches of land, which they cultivate based on the principles of monoculture, but they also poison nature, people and animals with vast quantities of agrotoxins, leading Brazil to become the world’s largest consumer of agricultural poisons.

Toxic agribusiness vs the agro-ecological model

In contrast to this toxic approach to agriculture is the agro-ecological model, which is premised on a comprehensive system of production that puts human relationships at its core. In the agro-ecological model, the health, culture, recreation and education of human beings are vital in the process of the production of agricultural goods. This model seeks to produce a range of healthy food, for instance, which must be grown in harmony with nature. The contest between toxic agribusiness and the agro-ecological model is at the centre of this dossier from Tricontinental’s Institute for Social Research in São Paulo.

Key to the agro-ecological model is the concept of popular agrarian reform, which proposes the full-scale reorganisation of landholdings. But first, an overview of the history of the struggle for land in Brazil. This history is key to understanding the dynamic of the popular movements that have developed the class struggle against the toxic agribusiness model and in support of a coherent agro-ecological alternative.

Related article:

On 17 April 1996, in the state of Pará, the military police attacked and killed 21 landless rural workers and wounded 69 others. The anniversary of what is known as the Massacre of Eldorado dos Carajás is now commemorated as the International Day of Struggle for Agrarian Reform. This story condenses the reality of land concentration, the impunity of landowners endorsed by the state, the extreme violence used against landless rural workers, the lack of a policy of agrarian reform and the radicalisation of rural workers in their struggle for a dignified life.

The return of popular struggles

The military dictatorship was unsustainable, which enabled diverse sectors of society to begin to wage struggles against it. It was in this period that various political organisations of the working class emerged, notably the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores) and the United Workers’ Central (Central Única dos Trabalhadores). In addition, groups that had become illegal – and therefore dormant – reasserted themselves, such as the National Union of Students (União Nacional dos Estudantes). These organisations and the struggles that they enabled and brought together grew slowly, eventually changing the correlation of the balance of forces and leading to the fall of the dictatorship.

The situation was no different in the countryside. One of the main contradictions that tumbled out of the Green Revolution was the expulsion of millions of workers from the countryside. Squatters, renters, wage labourers, sharecroppers and those evicted for the construction of dams were the social groups that created hotbeds of resistance against the dictatorship and the landowners. For them, the land occupations emerged as the main way to contest the latifundio and the dictatorship.

In 1984, the Landless Workers’ Movement (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, or MST) emerged out of these experiences. At its core, the MST has three main objectives. The first is the struggle for land, which corresponds to the immediate struggle of the landless to acquire a piece of land. The second is agrarian reform, because without an agrarian policy from the state that supports land reform and land rights, any land acquisition will only be temporary and those on the land will be threatened with expulsion. The third is social transformation, because there can be no long-term solution to the deep crisis of landlessness without a complete reconfiguration of the power relations in society, namely a transformation of the social relations of production and the hierarchies of society.

Land occupations as a weapon of struggle

The MST embraced land occupations as its main method for building power. The occupations have a dual function. First, they question the way in which land as private property is used to disenfranchise the majority of society – in stark contrast to land held communally and used for the public good. Second, they denounce the fact that land is not carrying out a “social function” as prescribed by the post-dictatorship 1988 Constitution, which outlines that all property must meet certain criteria, such as that it must be productive, it must respect environmental regulations and it must follow labour legislation. If these criteria are not met, the land can be appropriated in the name of agrarian reform. As part of the struggle led by the MST, roughly 350 000 families have acquired land, and an additional 80 000 families live in encampments spread throughout the country that are still struggling for legal status.

Related article:

Over the 36 years since the foundation of the MST, the struggle for land has gone through several different political moments, each moment met by popular struggles with different strategies and tactics appropriate to the class configuration and the power relations of that period.

In the early years, the primary confrontation was between the peasants who had been expelled from their land and the large landholders, the latifundiários. The Brazilian countryside in this phase was composed of archaic, backward and unproductive latifundios that used violence as their primary means to protect their enormous troves of private property. During the re-democratisation period of the 1980s, the MST expanded across the country, organising large occupations of latifundios led by thousands of landless families. Two key slogans propelled the struggle for land: “Without agrarian reform, there is no democracy” and “Occupation is the only solution”. It was through the occupation of parts of the latifundios by peasant families that the first settlements emerged; these settlements, where the families now lived and worked the land, became a material argument for agrarian reform.

Landowners’ retaliation backfires

As this wave of democratisation grew, the owners of the latifundios created the Democratic Association of Ruralists (União Democrática Ruralista, or UDR). The UDR was to rapidly become the weapon used violently by the large landholders against the MST as well as to lobby and pressure the federal government to act against the peasant movement. During the 1990s, when Brazil’s governments had adopted the neoliberal policy framework, the UDR – along with the state – went on a rampage against the landless and the MST. People suffered violent repression at peaceful demonstrations, the arrest and imprisonment of key organisers, and the attack on the civil rights of the secretariats related to agrarian reform, including the tapping of their phones and invasion of their offices.

The violence unleashed by the latifundiários and the state, as well as the unproductivity of the latifundio form, increased the appeal of agrarian reform in society. The landless struggle came to be widely recognised as a legitimate action. It was in this period that the MST carried out several land occupations, organised its bases for resistance and self-defence, and organised the occupied land around the collective production of food in cooperatives. This struggle went from the occupied land to the streets, with statewide marches and demands for agrarian reform at the federal level. During this period, the movement also strengthened its organisational capacity and sharpened its political line.

The consolidation of the neoliberal project marked a step backwards for the working class in Brazil. Nonetheless, agribusiness firms had not yet fully penetrated the countryside. The MST took advantage of this to organise its encampments and settlements. The movement carried out its first national march in 1997 to denounce the neoliberal project, demand justice for the victims and survivors of the Eldorado dos Carajás Massacre of 1996 and hold a dialogue with society. The movement grew rapidly – with international support – and emerged in this period as a key pillar of the Brazilian left.

Industrial capitalism and agrarian reform

The problems of national sovereignty and social equality cannot be addressed without a debate around the agrarian question. The emergence of capitalism from the 18th century had a marked impact on agricultural production, although the ways in which agriculture transformed varied across the world. What happened in Europe, for instance, was not entirely replicated in Brazil. However, it is useful to track the “classical” story first, because it gives us a template for the operations of capitalism in agriculture in order to then develop that story further in the case of Brazil.

From the 18th century to World War I there was a broad policy to reorganise landholdings from one part of the world to another. This massive redistribution of land dispossessed the peasantry and created large farms for landowners and for capitalist agriculture. This concentration of land took place alongside the development of the Industrial Revolution, which found it necessary to integrate the agrarian economy with the strategies of capitalist development. The Industrial Revolution drew in masses of dispossessed peasants and artisans, who were now forced to sell their labour power at the factory gates. A complex economy developed that was based on the exploitation of labour and the internationalisation of capital and markets. The agrarian question was a crucial element for the subordination of labour and natural resources to capitalist development.

Two central and related elements frame the agrarian question within the history of capitalism. The first is the push by the industrial bourgeoisie to supplant the old landowning rural classes, whose unproductive – in capitalist terms – use of the land was a hindrance to the accumulation dynamic of capitalism. The second is the assertion by industrial capital to set aside the logic of archaic feudalism and put its own capitalist logic at the centre of social development. The industrial bourgeoisie drove an agenda to bring the commercial logic of industrial capitalism into the fields, but also to ensure that the state’s economic policy would be shaped around the needs of industry rather than the needs of agriculture. The accumulation of capital became centred around industrial development; the creation of a cheap workforce and an abundance of raw materials became necessities for the economy as a whole.

However, the “democratisation” of the land that followed – namely the relative loss of power of the landlords – did not benefit the peasantry. Instead, the outcome was that the agricultural sector – even its medium- and small-sized farms – would be subordinated to provide raw materials for the growing industrial sector at lowered prices. The delivery of cheapened food to cities allowed industrial firms to pay lower wages, because the cost of social reproduction had been suppressed by the weakened place of agricultural producers in society. As agricultural land became more productive, peasants were displaced to become factory workers, while those who remained were consolidated into an expanding consumer market.

Capitalism strengthens its position

The revitalisation of the countryside’s economic capacity took place at the cost of its subordination to the city and, in particular, to industrial capitalism. It was in this context that many countries across the world conducted capitalist agrarian reform. Most European countries went through this process, though this was not a European story alone. In Japan, almost three million people became landholders as a consequence of its land reform, while in Turkey plots larger than 500ha were expropriated. In Italy, the state expropriated land with compensation paid to landowners, developed infrastructure in the countryside, reclaimed degraded land and built houses for peasants. In each of these cases, the peasantry was subordinated to the logic of capitalism and the benefits of reform were absorbed for capital accumulation – not for the wellbeing of the peasantry.

The process of agricultural production began to be defined by the capitalist mode of production. The fear of unemployment and the speed of production began to be determined less by the lash (as had been the case in slave plantations and in feudal estates) and more by the time discipline of the managers. Capital defines what to produce and how to produce it; capitalist firms define the depth of commercialisation and the compensation received by the various levels of field workers. Peasants no longer had any semblance of control over the means of production. Indeed, the peasantry in most parts of the world lost not only the means of production; it also lost the centrality of its cultural forms.

Capitalist dynamics entered rural areas with their own cultural logic; they encroached on and denied peasant culture’s ideas of production and consumption, especially the growing and eating of food. A transformation of social rules took place that replaced the organisation of social life around cooperation and social integration with individualism and dependence on the capitalist market. In this sense, classical capitalist agrarian reform was part of the policy of the bourgeois state and was carried out to benefit the dominant class of that time, the industrial bourgeoisie.

The Green Revolution and the neoliberal model

Despite many similarities, several key differences separate the case of Brazil from the transformations of capitalism and agriculture seen in Europe. For instance, in Brazil there was no fundamental separation between the rural oligarchy and the industrial bourgeoisie. They were intimately linked class fractions, and the emergence of the power of the industrial bourgeoisie did not take place by defeating the rural oligarchy. Land concentration was not an obstacle to capitalist development in Brazil. On the contrary, there was unity between the latifundio and industrial capital, an alliance between capital and state-mediated land ownership. The high concentration of land at low rates of productivity nonetheless forced a rural exodus that created a significant reserve industrial army whose presence held down wages. The harshness of the rural economy subsidised industrial production and the accumulation of capital by the industrial bourgeoisie.

Unlike in Europe, in Brazil there was no effective national policy for agrarian reorganisation. Instead, an agrarian tripod developed: latifundios, heavy mechanisation and agrochemicals that were organised around the United States model of agribusiness known as the Green Revolution, which began in the 1970s but intensified over the next two decades. The model that emerged from the Green Revolution was entirely premised on capitalism’s interests, with the peasantry merely a factor of production.

Related article:

In the 1990s, as the Green Revolution intensified in Brazil, the country’s agricultural landscape underwent significant structural transformation. Notably, there was a shift in the way that the production of agricultural commodities was organised. The key element here in terms of the agrarian question was the emergence of the neoliberal model and the strengthening of agribusiness firms over agricultural production and the distribution of agricultural goods, edging out small and medium-sized landowners. The archaic landowners who owned large tracts of land allied themselves with the other fractions of the bourgeoisie – those who dominated transnational agricultural corporations, financial firms and institutions of the mass media. The hold that these landowners had on the land was undiminished; they now provided their vast acreage and their domination over the workforce to the international market through this agribusiness ensemble – corporations, banks and the media.

As the capitalist system has entered into a serious crisis of profitability over the past few decades, the agribusiness sector has searched for ways to maintain or increase profits. These methods include the intensification of environmental destruction, expansion of the agricultural frontier over forests and common land, deepened ferocity of mineral extraction, and the consequential increased harshness towards the workforce, who saw not only the demands upon their bodies increase, but also watched the common lands disappear.

As agribusiness becomes more complex and deepens its hold on the political economy, popular agrarian reform has become a real and necessary alternative. The features of popular agrarian reform move in a radical direction, towards the rejection of capitalist control over the world of agriculture – including land – and towards the reorganisation of agriculture and the environment and the needs of people and nature rather than profit.