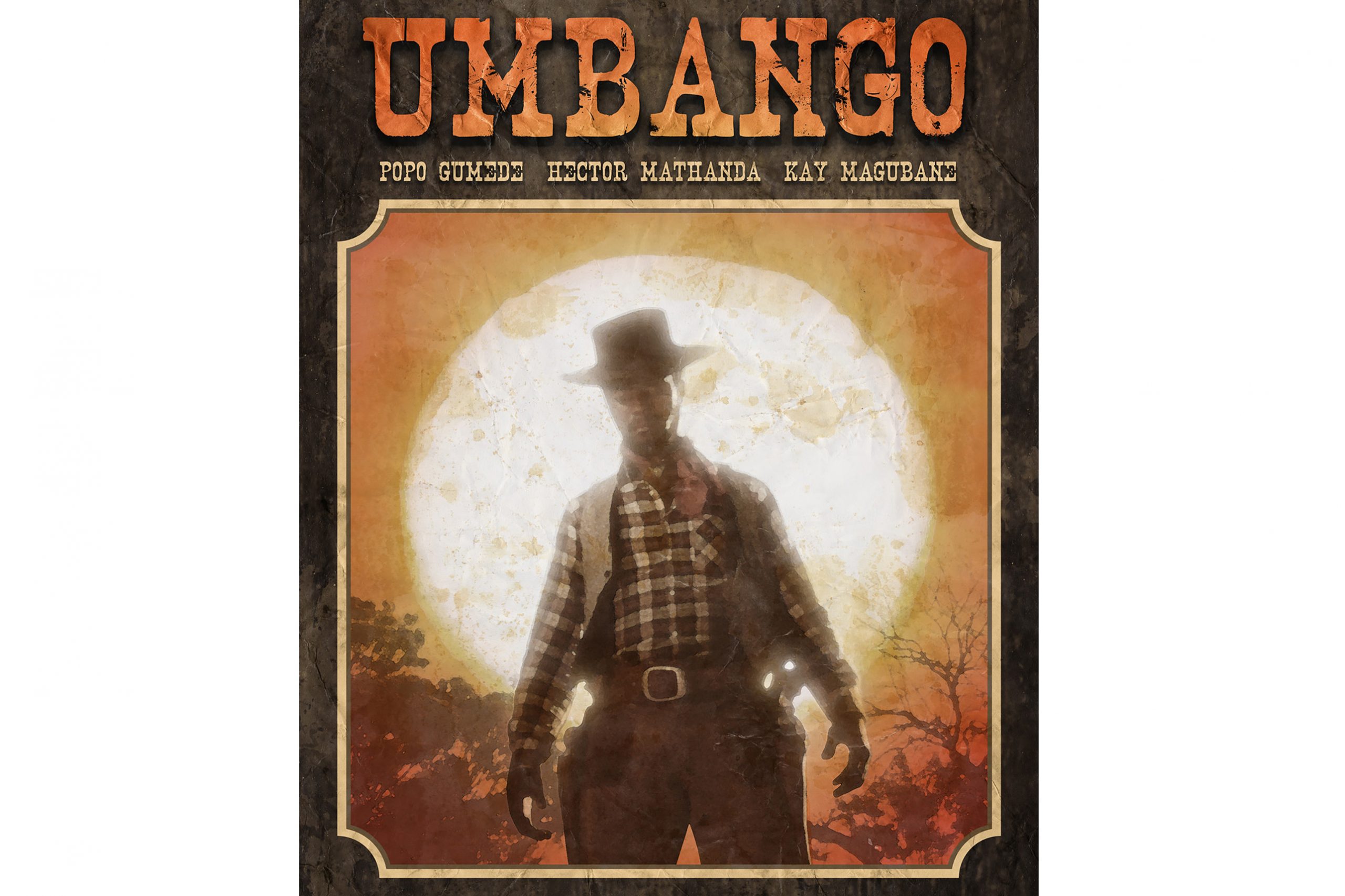

‘Umbango’, South Africa’s original western

The 1986 film was part of apartheid’s scheme to keep township dwellers docile through cinematic escapism. It backfired and now the cult hit has been newly digitised and restored.

Author:

28 August 2020

Innocent Gumede is the most charismatic South African leading man you’ve never heard of. Time and our nation’s selective memory seems to have forgotten him. Before he embraced the promotion back to sovereign citizen in 1994, started a family and moved to KwaMashu, Durban, where he now lives with his fiancée Mbali and their kids, Gumede was a heartthrob.

With a scruffy beard and a tightly packed Afro, he has the rustic feel of Yonda Thomas and, on screen, the effortless charm of Paul Newman. So, it’s no small wonder that in the 1980s, after spending years as a history teacher and amateur football scout, Gumede became an accidental superstar.

“I was called by a friend of mine who lived next to my house. He told me they were doing auditions at the SABC, and I tagged along and did a screen test,” says Gumede. “I was given some great advice before going on. Someone told me that I must treat the camera like I don’t care about it, like it’s nothing. I guess that’s where I got my confidence from.”

The Inanda-born actor was cast as a TV presenter, and before long he would become a household name for his roles in Operation Hit Squad (1987), Ambushed (1988) and Rich Girl (1990). Gumede had amazing emotional range for an untrained performer, and nowhere is that more apparent than in his performance in the cult hit Umbango (1986).

Contrary to popular belief, this film was the first western ever made in South Africa – not 2017’s Five Fingers for Marseilles. The film was directed by Tonie van der Merwe, best known for Joe Bullet (1973) and Trompie (1975), the movie that inspired the band name of the kwaito supergroup Trompies.

Apartheid’s B-scheme

Umbango follows a simple story. Tough guy Jet and his friend Owen must protect themselves from a grifter named Kay Kay, who comes to town to claim revenge and his brother’s land after the latter is killed – supposedly because Jet snitched on him.

“The premise of the film was very basic, and I guess that’s a hallmark of my work. The story must be clear. You must walk in and get it. I’m not trying to trick the audience,” says Van der Merwe. “My interest is in creating characters that you care about and entertain you.”

Umbango was part of the B-scheme, an attempt by the apartheid government to create and fund a slate of films for black audiences with black casts, but most of which were written and directed by white filmmakers. The scheme was a transparent attempt at distracting people in the townships through the escapism of the cinema. Through a network of churches, hostels and community halls, filmmakers made films that reached about seven million people in the townships every month.

Related article:

“Initially the government was funding only white filmmakers, and they didn’t care about what was going on [in] the townships, so they gave us a little bit of money to make these films,” says Van der Merwe. “Then when they realised we were making films like Joe Bullet, where there is a black guy who is a hero and can fight and is wielding guns, they started to watch us very closely.”

The B-scheme would eventually collapse because of financial mismanagement by the government, according to Van der Merwe. “People think corruption is a new thing, but back then there was a lot of corruption and people were stealing money from the funds that were supposed to make films. They wanted bribes, too, if you got funding, so eventually making a film just became impossible.”

1986 was a difficult year in South Africa. Civil unrest and bombings became commonplace and the government declared a national state of emergency. Reflecting on this, Van der Merwe and Gumede note that although there was a lot going on politically, they still felt that audiences needed to be entertained. When tragedy is so rampant, spectacle offers a welcome escape.

“It was a dilemma that I often struggled with because often I felt what we were doing was frivolous, but most times I understood that people needed reminders that there was another kind of life possible. Black people wanted to be entertained and see themselves reflected on screens in a new way,” Gumede says.

Mining something deeper

Umbango is packed with tense faces and hilarious turns of phrase. Comedy and tragedy are closely balanced in the western.

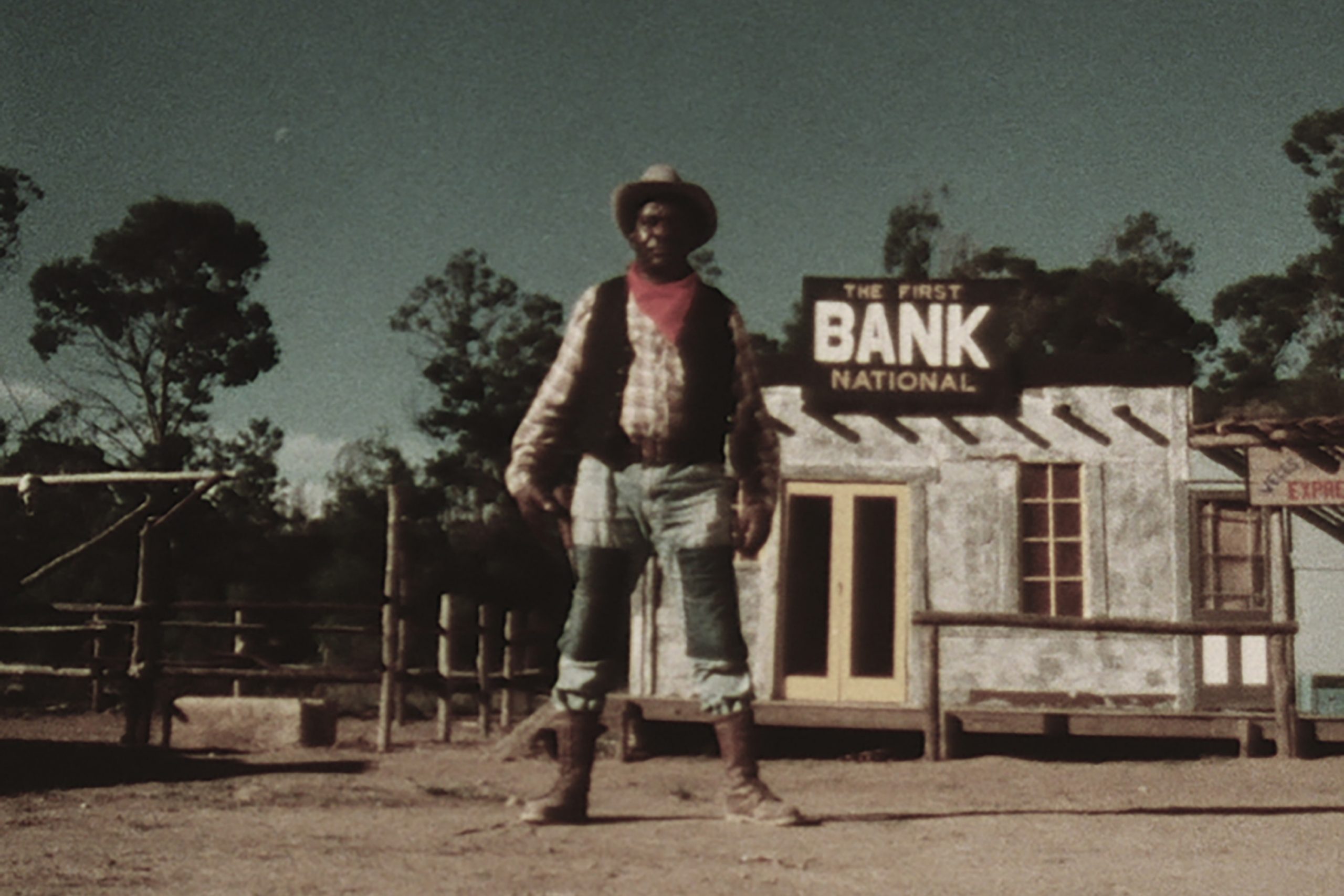

Visually, the film is peppered with chrome blue skies, short takes of rolling vistas and close-ups of boots and sweating skin. It starts off mimicking the old language of spaghetti westerns made by Sergio Leone, but by the end of its running time, it posits something deeper about the time and era in which it was made.

Rooted inside Van der Merwe as a filmmaker is a profound sense of patriotism. And what better way to be a patriot than to see your country clearly. No other filmmaker from the era, and maybe even since, has been so prolific in mining the length and breadth of South Africa for both its visual splendour and haunting stories.

Having been born into a staunch Afrikaner family and then graduating to work closely with black talent, and deeply conflicted by his place in the country, Van der Merwe did not mute his sense of guilt. Instead, he used it to make sense of the world around him through the narratives in his films. Social status – the unbridgeable power gap between the haves and the have-nots – tears apart Van der Merwe’s characters in Umbango, much like it does to us today.

By using the apartheid government’s money to make an allegorical film about it, Van der Merwe used the master’s own tools to show what a monster it was. Nonetheless, he recognises he could have done more to undermine apartheid.

Related article:

“I think that is the deepest regret of my life that I spent so many years thinking of myself only as an apolitical filmmaker. In hindsight, I know I should have been more vocal,” says Van der Merwe, who now lives with his wife in Cape Town.

“I was working with black actors and talent, and they were being tracked by the security police and being harassed. Some of them were not even allowed to see these films in certain spaces. It was just a nightmare. I spent such a long time worried about my films and the work that I did and said nothing about what was really going on all around us.”

Van der Merwe’s silence was motivated by a desire to make money and a name for himself. He had experienced what it was like to have his work banned and censored when he made his first film, Joe Bullet, and wasn’t going to let that happen again. His place in South African film will always be complicated by the fact that while he wasn’t an apartheid propagandist, he was certainly a beneficiary of the system. He grapples with this in Umbango, and in retrospect, but perhaps not to the extent that he could and should have.

Gumede’s mastery and metaphor

On screen, Gumede’s Jet is unlike any other character. Underneath his thinly veiled bravado is the reality that he, much like the nation he inhabits, is overwhelmed by the constant state of nervousness that comes from a life of perpetual violence. He is a metaphor for black South Africa under apartheid. He is looking for land, a place to call his own and a new start, but he is held hostage by his past and sees no other way to set himself free than a return to the violence that’s been visited upon him. Here, even death is better than bondage.

“The struggle for freedom was a very relatable one for me,” says Gumede. “When you see people around you dying all the time, you long for that life of just wanting to escape. Jet wants to escape and find himself some land and breed horses. My temporary escape from the reality of apartheid was making movies.”

The most powerful statement made in Umbango is not only how it centres black people in a genre that even now is predominantly dominated by whiteness, but it is also how white people are treated in the film. There is one white character named Gringo. He is voiceless, and after declining an offer to come work for the antagonist, Kay Kay, he is shot and killed in a bar. His death is incidental and unremarkable and has no consequences for the black man who kills him. At the height of apartheid, when white lives were seen as inherently more valuable than black ones, this was radical.

Technical challenges

Umbango was not an easy film to make, not only because of the political climate but also for technical reasons. Filming exteriors under the beating Midlands sun proved a challenge because of a low budget and lack of light coverage.

“We had next to no money for the film, and we shot for about a week at the Sierra Ranch in Mooi River using sets from another movie,” recalls Van der Merwe. “We were also afraid the production would shut down because we knew the security police were on us trying to find out exactly what we were doing.”

Related article:

But the equipment and spies were not the only challenge. Gumede laughs as he recalls a day on which fellow cast member Hector Manthanda was scheduled to shoot his dying sequence and kept intentionally ruining the takes so he could have an extra day on set. Manthanda was trying to cash in on the R80 a day he and the cast were getting paid.

“He would keel over and then ruin the take at the last second by looking up or laughing, and he kept doing this and wasting the blood that we had until he got his extra day,” says Gumede, chuckling.

A crowning achievement

Umbango is Van der Merwe’s crowning achievement. It transports you to the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands. In this age where editing and technical cosmetics are commonplace, the lived-in quality and painterly nature of the film puts it in a class of its own. It is a shame that the small screen is the only way to see it now.

Umbango is part of a small collection of films that have been digitised and restored by Gravel Road films as part of its Retro Afrika bioscope project. According to Ben Cowley, one of the curators behind the initiative, part of why Umbango is one of the films selected is because of its idiosyncratic perspective.

“People always love genre films, and the western is a genre that people mostly associate with America. For people to see this Zulu western made at the height of apartheid is quaint, but they’re also surprised by how rich the story is and how fun the characters are,” says Cowley.

Although Umbango is unlikely to be seen by the wide audience it deserves, Van der Merwe hopes that the few who do get to catch it on streaming services will be transported into a world of vibrant images, and that viewers come out the other side transformed by some truth found in this fictional world.

“I just want people to see the films and enjoy them, but also [to] look for something that mirrors their own life, regardless of where or when they see the movie. If that happens, I’ve fulfilled my purpose.”