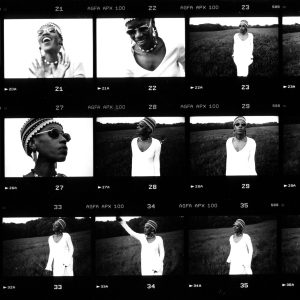

Vignettes on our godmother, Busi Mhlongo

In a series of sketches, musician and writer Nakhane reflects on the enduring effect of Busi Mhlongo as her breakout album Urban Zulu is reissued on vinyl.

Author:

25 June 2020

1.

What does it say about an artist’s mutability when in this day and age of instant gratification online platforms, most of their available discography is remixes? Those songs are transferable from the past and into the future. On dance floors, kids who had never heard the originals are still transfixed by that voice. That voice which could begin a phrase in gossamer tones, in a coo; move to a thunderous growl and end in the most harrowing and tremulous vibrato. That voice which could be supported by acoustic guitars and the most manic programmed drums.

2.

My first memory of Busi Mhlongo was of her surrounded by some of South Africa’s best black woman singers. She was the fading high priestess and around her were her beaming, yet heartbroken acolytes. The cancer was winning and she was succumbing. Spread on what I remember being a chaise longue on a stage with a screen behind her, we watched her looking so regal, stretching wide an appreciative and touched smile. What these women were doing for her – singing in a televised benefit to raise money for her hospital bills – was noble. But nobleness does not reverse the irrevocable damage cancer can do to the mortal frame. Nobleness; no, charity, however well-meaning does not and cannot give energy to what is sapped.

I walked past the television, glimpsed what I remember being small, sad eyes and I thought that she looked tired.

3.

Memory and time can be sparring friends. Years may seem like months when they were actually weeks, and these weeks were actually days. Emotions and seasons get tangled, and what was about place becomes about what was felt. For example: I remember the curtain in our living room being left open – which was uncharacteristic of our household – and I remember it being cold that night; and I learnt quite passively and with no real damage done to me, that Busi Mhlongo had died.

There is something that I know for certain: It would be years before I would be confronted with my passivity. My conscience and the glare of history would not permit me anymore of it. Soon I would join the many of my generation and transform that passivity to hot passion.

4.

I was green and startled.

I was hungry.

I was listening to hundreds of albums a year. I had never been more of a voracious reader; and though money was getting tighter by the day my eyes were squarer still: not from the movie theatre or rented films like before, but from pirated films passed on from friend to friend.

I was in search of the Holy Grail.

A nugget of it was given to me one afternoon in a Braamfontein bar. A wind rushed in and blew everything I was so sure of away. I could hear her in what I knew, in the musicians that were now being heralded. But they were mere satellites. What I was experiencing now was the sun. The actual life-giving source.

Related article:

The song was Ukuthula, the fourth track from Urban Zulu. The hallmarks of tradition are there in the interlocking guitars and vocal melody. But something else is happening and it is difficult to explain.

– Is it her defiant vocal?

– Those multi-tracked counterpoints which are sometimes just inside the harmonic structure of the song?

– Is it the pitter-patter of the drums which could easily be ham-fisted in a song this driving?

– What about the skittering and buoyant bass?

Whatever we decide it is, what is demonstrated in the recording is an artist who has not only mastered the tradition, but one who has come into their own.

I paused that song and said, “Thandiswa Mazwai has stolen so much from her.” My friend interjected with a pointed finger: “No. It’s not theft, it’s inspiration. It’s influence.” I agreed without remonstration. Busi was the trunk, and out of it one of the boughs that grew was Thandiswa. Even if I had not been corrected I would not have blamed Thandiswa if indeed she had ‘stolen’ something from this. What does a flower do when it is finally exposed to the sun after spending time in the dark? It can’t help but lean in its direction.

Marking the 10 years gone by since Mhlongo’s passing, Thandiswa took to Instagram to celebrate her legacy: “Nothing like it! One of the most powerful and transformative voices to come out of Africa … With an entire school of vocalists, including myself, as avid students of her craft and message of love and unity, she lives on. I was completely changed by, not only the sounds that she made, but the unforgettable sight of her. When her mouth would shake from side to side producing something that at once sounded like a wailing and a cheering. She roared like thunder but still managed to cover you with a feeling of fellowship and divine presence.”

Related article:

5.

It’s easy to cast Busi Mhlongo in the role of the defeated woman in need of rescuing. It’s also inaccurate.

In an interview captured in London (date unknown), she speaks about the difficulties of being a woman musician in a world ruled by belligerent men, who had women literally running up to them to give them a chance if they proved themselves hungry enough. It’s in the same interview that she also speaks about how when she was in these bands – singing and dancing – image was of utmost importance: image, as in social strictures. Speaking with an easy lilting laugh she says, “…It was not like now where you can be everything. Freedom. Total freedom. Even on stage, you know. You had such image that you don’t want people to see you picking up your leg, because then they’re gonna say you’re not a lady… You always try to protect your image.”

Related article:

Perhaps she did not fight these men who abused her with physical power; the ones (as reported by Niren Tolsi on The Mail & Guardian) who left cigarette burns on her wrist. Or the ones who used their power and position to exploit her in the music industry. Her power was in song. Her music was never meant to soothe. It always kicked! Others may disagree. “It’s just a song,” they may say. “What about the perpetrators? What about justice?”

I’m reminded of a scene in Ferdinand Oyono’s novel, Houseboy, where Toundi (the titular character), jaded and disillusioned by Christianity and cruelty of whiteness, forgoes standard forms of protest and retaliation. In their stead he decides to spit in The Commandant’s drink before serving it to him. The Commandant may never find out about Toundi’s deeds. He may never change as a character, but Toundi does. And this small action, done in secret was never for The Commandant, but for Toundi.

Busi Mhlongo’s defiance is the spittle. She heals herself.

Related article:

6.

“I was always running,” she pauses and realises that she might need to clarify herself, “to the music. This is it. This is what God brought me here for. This is my task.”

And what a way to do that task.

To a country and world that was thankless to the point that people had to donate money so that her bills could be paid. Accepting help is brave, but how much humility did she have to conjure up to sit on that stage as sick as she was?

What a task. To be a conduit for the past. To take maskandi, shake it loose of its macho mythology and bring it to the future feminised.

Urban Zulu, a political album that runs the gamut of politics – from personal right through to social. But closest to its heart is peace. It demands peace for Africans. It shakes you into understanding its importance. It’s non-violent, but it is never ever pacifist. That’s what she does for us now, us musicians who are still in this world. She shakes us in our seats to be better. For the world to be better.