What’s in a name when it comes to sports teams?

Quite a lot, it turns out, as teams and clubs around the world are being forced to reckon with the racist origins of their names, branding and imagery.

Author:

19 September 2020

Imagine an alternate universe in which the Nazis win World War II and Adolf Hitler’s dream of a pan-European ethnostate is realised. Once the rubble is cleared, organised sport resumes across the continent.

One top-tier football club based in the area formerly known as Poland is called the Warsaw Gold Stars. They play in vertical, blue and white stripes. Their team logo depicts a man with a large hooked nose, thick bushy eyebrows, dark curly hair and a black hat. The mascot, prominent at every home game, mirrors this figure and walks with a hunched back and an awkward gait. Yudel, as the mascot is affectionately known, carries a small bag of fake gold coins, much to the amusement of young fans in the stands.

If this sounds ridiculous, grossly offensive even, consider the reality that exists in the United States today. In a country where indigenous people endured their own version of a holocaust and now comprise less than 1% of the population, Native American history has long been bastardised in professional and amateur sports.

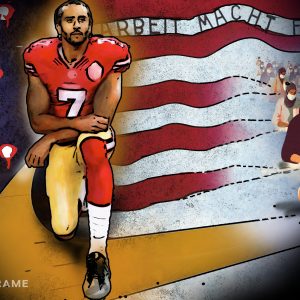

The lengthy list – hundreds of high schools and colleges use Native American motifs or names in their athletic programmes – was reduced by one on 13 July when the Washington-based National Football League (NFL) team announced that it would no longer be called the Redskins, a term long viewed as racist.

Related article:

Native American groups have campaigned since the 1960s for the removal of harmful stereotypes of their people in sports, but have largely been ignored. Daniel Snyder, the owner since 1999 of what is now called the Washington Football Team, said in 2013: “We’ll never change the name. It’s that simple.”

Rather than a bolt of consciousness, Snyder’s arm was twisted when a group of 87 investors and shareholders urged major sponsors to terminate their relationship with the franchise unless sweeping changes were implemented. He relented in what the Navajo Nation described as a “historic day for all indigenous peoples”.

Attention has since turned to the few remaining elite teams in US sport that still use Native American iconography. The Chicago Blackhawks in the National Hockey League clad their players and stadium in a caricature of a Native American warrior, replete with face paint and colourful feathers. In Major League Baseball, the Atlanta Braves and the Cleveland Indians have yet to fully disentangle themselves from their racist histories, though they have disbanded their overtly offensive logos.

The most recent Super Bowl winners, the Kansas City Chiefs, remain the only side in the NFL mired in this controversy as fans at Arrowhead Stadium wear ornate headdresses and sway their arms in unison in a move called the “tomahawk chop”.

“The fight continues,” says LeAndra Nephin, an activist and domestic abuse therapist who is part of the Omaha Tribe. “The events in Washington are seen as just a step in the right direction. We’ll celebrate the win but we know there is a long way to go.”

Inappropriate branding

A month before change came to the US capital, Exeter Chiefs rugby fans established a pressure group in southwest England called Exeter Chiefs For Change. It had gathered more than 4 500 signatures for its petition to change the imagery and branding of the club at the time of writing. The rugby union club based in Devon was founded in 1871 and gave the nickname “Chiefs” to its first XV in the 1930s.

It wasn’t until 1999, when Exeter Chiefs turned semi-professional, that it adopted its current logo of a stereotypical Native American chief. Soon, fans adorned in feathers and war paint were downing pints at the Wigwam bar while Big Chief, the club’s mascot, acted as cheerleader.

Related article:

“We are advocating for the removal of all connections with Native Americans from the club,” explains Alix Burhouse, a lifelong Exeter fan and leading figure in the pressure group. “I’ve worn the merchandise and embraced the environment, but the world is changing and it’s important to be on the right side of history. We are listening to Native Americans and they are telling us that change is needed at our club.”

The Exeter Chiefs board agreed that the mascot was offensive and dropped it. It did not, however, see any problem with much else. “The Chiefs logo was in fact highly respectful,” it said. The club would not comment further on the matter.

“They have made a conscious decision to remain a racist club,” Nephin explains. “Despite all the evidence we have presented them, their cognitive dissonance is deafening.”

‘A triumph of racial hierarchy’

Nephin was raised on the Omaha Reservation in the US state of Nebraska. She grew up with a strong sense of community and has fond memories of hunting trips with her father and of foraging for blackberries and rhubarb with her friends. This is the idyllic version of events that many non-indigenous people imagine is ubiquitous throughout the 326 “Indian” reservations in the country. But it is not a complete picture.

“I grew up with violence and an understanding of poverty,” Nephin explains. “From a young age I was bombarded by the stereotype of the lazy, drunk Indian and that impacts your sense of self. Then there was the notion of the noble savage evoked by these sports teams and it didn’t add up. I grew up angry and have lived my life with a strong urge to counter these descriptions. If this is how they show my people honour, then I don’t want it.”

Now living in the United Kingdom, where she is working towards a degree in cognitive behavioural therapy at Oxford University, Nephin can’t help but feel a familiar pain when confronted with the stubborn resistance of the Exeter Chiefs board.

Related article:

“This is where the people who decimated my ancestors and confined my people to a life of torment came from,” she says. “Using a deformed image of us as their mascot is not a sign of respect. This is a triumph of racial hierarchy and the hegemony of white supremacy playing out in the land of the coloniser.”

The moniker “Chief” is not in and of itself problematic. As Burhouse points out, the context of place is important. In Waikato, New Zealand, players for the Chiefs rugby union side wear a badge that depicts a Māori warrior holding a traditional kotiate weapon. Conversely, in South Africa, the logo of football powerhouse Kaizer Chiefs is that of a Native American archetype rather than a chieftain from a local tribe, despite the club’s isiZulu nickname of Amakhosi.

“We understand that the name Chiefs has been linked with the [Exeter] club for a long time, but we believe it can be rebranded to represent an Anglo-Saxon chief or something more aligned with the region’s history,” Burhouse says. “It is the current guise that is causing harm. We’re not trying to rewrite history.”

Moving goalposts

Not all sports teams that use the images or names of indigenous peoples are inherently racist and problematic. The Māori All Blacks are a rugby union side from New Zealand that champions the country’s Polynesian roots. To play for the team, players must have Māori heritage.

Other indigenous people represented in sports teams do not garner the same negative attention. Basketball team the Boston Celtics and football franchise the Minnesota Vikings depict stereotypes of Irish and Scandanavian cultures respectively on their crests in a nod to their regional histories. Why should these be acceptable when the Blackhawks or Exeter Chiefs are not?

“It’s about representation,” Nephin explains. “Irish and Scandinavian people are represented in a diverse way in mainstream media, in pop culture and in politics. This is not true for Native Americans who continue to live with the violence meted out to us.”

Violence often leads to change. The Canterbury Crusaders, arguably the most successful rugby union side in the world, was faced with a difficult decision after a white supremacist opened fire on two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, on 15 March last year, killing 51 people and injuring 49 others.

Related article:

As the incident carried overtones of a religious war, the Crusaders, whose name derives from the medieval Crusades of Christian armies into Muslim-controlled land, scrapped their logo depicting a chain mail-wearing, sword-wielding knight. They also cancelled pre-match entertainment featuring men on horseback.

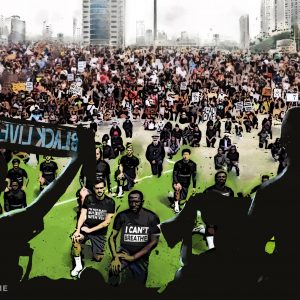

“There won’t be a one-size-fits-all approach,” Nephin says. “The goalposts will continue to move as we evolve our thinking. That can be scary for some people who are afraid of change. But it’s important that we listen to those who are feeling pain. It is not enough to simply be against racism. We all need to be actively anti-racist.”