Why consumer boycotts trump social media outrage

Boycotting a company or brand is far more likely to effect meaningful change. But it requires an ability to mobilise people that is now beyond political parties and many activists.

Author:

28 September 2020

Mobilising many people is always more difficult than venting on social media or sending a few people to make trouble at a mall. But it is also likely to produce deeper change, which makes it interesting that South Africans who say they want change prefer the easy options.

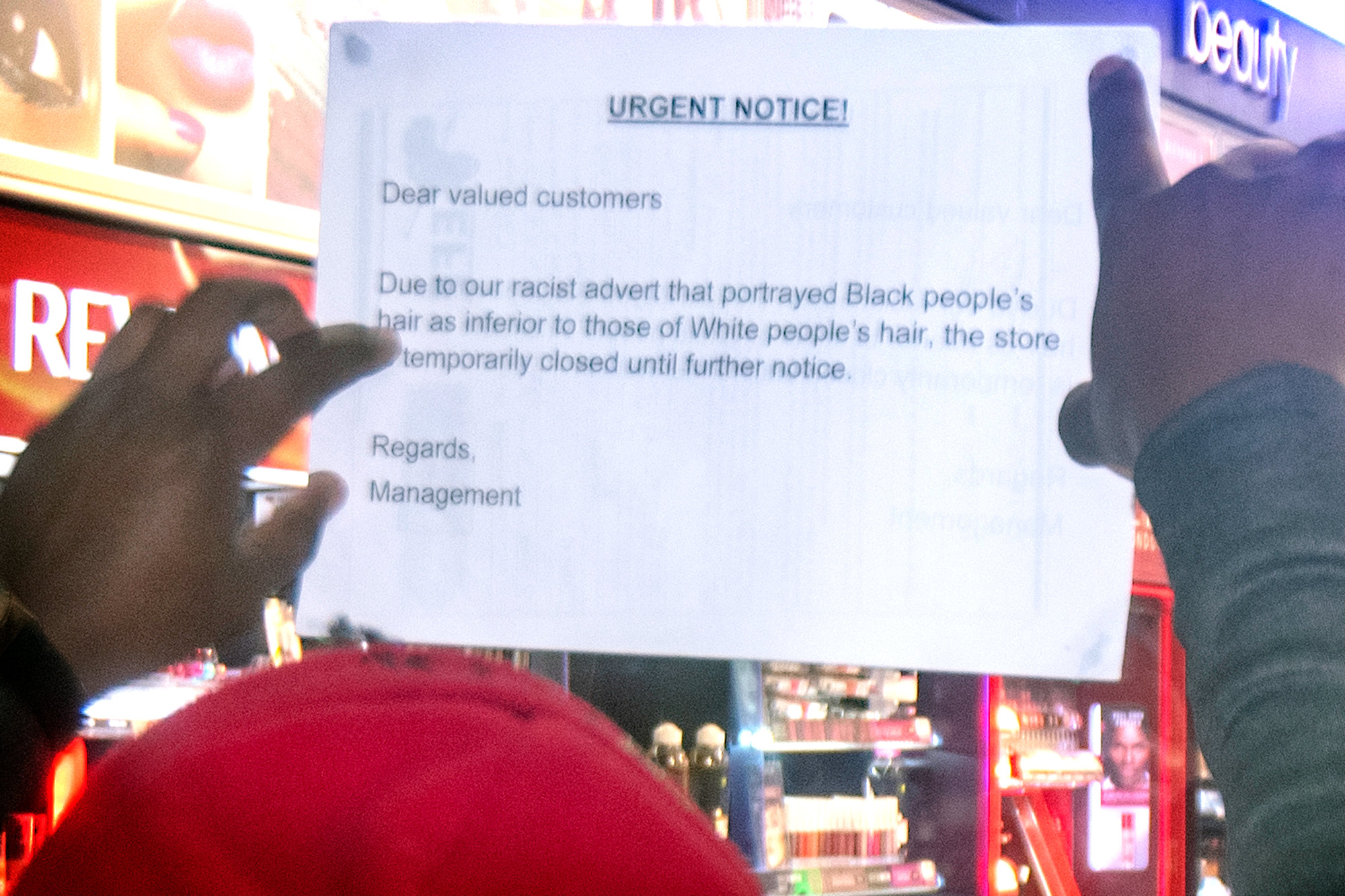

When retail store Clicks allowed on its website an advertisement that denigrated black people, women in particular, people angered by this were in effect told that they had two options. They could, as University of the Witwatersrand vice-chancellor Adam Habib recommended, hope that the Human Rights Commission would look into Clicks’ conduct. Or they could cheer on the EFF as its members gathered outside the company’s stores, forcing them to close and manhandling a woman journalist along the way. Few people pointed out that a better option was entirely ignored: a consumer boycott.

For two reasons, it is surprising that this option was ignored. First, the Clicks incident met the test for an effective consumer boycott. These boycotts are most likely to hit hard when people can join without making huge sacrifices. Asking people to boycott red meat, as a trade union once did, is less liable to work among meat eaters than asking them to boycott a brand, because then they don’t have to go without. People who were angry with Clicks could find the products they needed at other stores.

Boycotts are also most effective when many people believe they are needed. A boycott of Woolworths a few years ago by Palestine solidarity activists was an object lesson in what not to do. They declared that the company had not behaved worse than its competitors. But it had more of a conscience, so it should heed their demands. This was another way of saying that they thought it was a softer touch than the others. Predictably, even the most well-disposed people did not see why they should single out a company that behaved slightly better than the others.

The Clicks advertisement shocked just about everyone, making it much more likely that people – other than the usual suburban voices who would not join a boycott that protested against racism in any event – would have heeded the call to take their business elsewhere.

A rich history of boycotts

Consumer boycotts were once a much-used tool in the fight for justice in South Africa, making it all the more striking that they have fallen into disuse. Isolating the apartheid state internationally through boycotts was a central weapon of the campaign against racial domination.

In the 1950s, people rallied behind the potato boycott, called because potato farmers used forced prison labour. The boycott of buses by the people of Alexandra, in northern Johannesburg, gripped the imagination of people who opposed apartheid. During the 1980s, the consumer boycott was a frequent tactic to force white-owned businesses to pressure the authorities to negotiate. These boycotts were less well supported than they might have been, because they forced people to go without certain basic goods or buy them at higher prices in the townships. Force was sometimes used to get people to comply, but they did achieve their aim in some parts of the country. The trade union movement also called lengthy boycotts in support of demands for bargaining rights: Fattis & Monis foods and Wilson-Rowntree sweets were prominent targets.

All these boycotts occurred under white rule. Since 1994, the tactic has hardly been used, even when alternatives to products were available and public opinion seemed sympathetic to the boycotters’ demands. One reason may be that activists assumed that the tactic was no longer needed because democracy had been achieved. It took most social justice activists a long time to shake off the idea that, because the government was comprised of people who fought against apartheid, they and it were really on the same side.

Related article:

It was common for many years after 1994 for activists to assume that the government should listen because it was meant to support the same values. In reality, all democratic governments are likely to do what activists want only if they are convinced that they are up against a strong, organised force that they cannot afford to ignore.

The Jacob Zuma years ended that illusion. But they also revealed how weak social activism has become. Anti-Zuma protests attracted only a handful of people. None mobilised more than about 5 000, which included suburbanites who would not go anywhere near a social justice demonstration. Even union rallies, which once attracted tens of thousands, were attended by a fraction of that. Since Zuma left office, demands for a fairer society often seem to be confined to social media.

Marginal victory at best

This tells us why the consumer boycott is no longer used. Boycotts require an ability to reach out to people to persuade them to join. As it can be a long time before the boycott achieves its goals, this needs to be sustained by activities that keep people motivated. Boycott organisers need strong enough roots in society to persuade people and enough organising ability to sustain their support for a long time.

Boycotts, like strikes, are also democracy schools, because unless you use violence to bully people, you can’t get them to stay on board unless you take their concerns and opinions seriously. Sadly, all of this is now way beyond most citizen organisations in this country that claim to be concerned with social justice, including political parties. Sounding off on social media has become a substitute for mobilising people.

But why should people engage in lengthy boycotts when they can get what they want by doing what the EFF did? Social media has been abuzz with claims that the EFF tactic “worked”.

Related article:

The advertisement did not just insult the EFF, it offended millions. The deal the EFF reached with Clicks reflected what its leadership wanted, but it may not be what most people who were angered wanted. Consumer boycotts make it more likely that a settlement broadly fits the wishes of the people who boycotted.

An extended consumer boycott may have forced the company to make more concessions and, more importantly, take black concerns seriously because it would be trying to win back the support of many consumers, not to get a small group of activists off its back.

Even if the deal between Clicks and the EFF met the needs of millions of people angered by racism, we don’t know how effectively it will be enforced. Consumer boycotts are more likely to produce lasting change because there is no guarantee that, once people have decided to stop shopping at a store or buying products, they will return after the boycott ends. The company needs to win them back.

Boycotts are not the only way of winning change, but they are a more democratic way. And they are far more likely to achieve real change, because the collective effort of many people has a far more lasting impact than a small, threatening crowd. It can shift balances of power precisely because so many more people act to get what they want. Real change comes from the combined efforts of many people. Consumer boycotts require that in a way small but loud crowds do not.