Wounds of Ellis Park disaster still raw 18 years on

The mother of the youngest victim in the Ellis Park disaster recollects that tragic day and continues her call for the PSL to do more to honour the 43 people who lost their lives.

Author:

11 April 2019

Rosswin Nation, 11, was so excited to be going to the Soweto derby between Orlando Pirates and Kaizer Chiefs that after his father Roy surprised him with a ticket, he didn’t even have time to kiss his mother Annette goodbye properly.

Who can begin, then, to fathom the emotions Roy Nation has had to contend with for the past 18 years in dealing with the fact that he never returned with his son from Ellis Park Stadium?

Many of us have been Rosswin, thrilled by the prospect of the crowd, the exhilaration of seeing our sporting heroes perform right there in front of our eyes, going to a match with our father. We may have been Annette Nation, kissing our son goodbye. The scene and characters are familiar to most.

On Wednesday 11 April 2001, Rosswin was the youngest of 43 football supporters who did not leave the stadium alive that night.

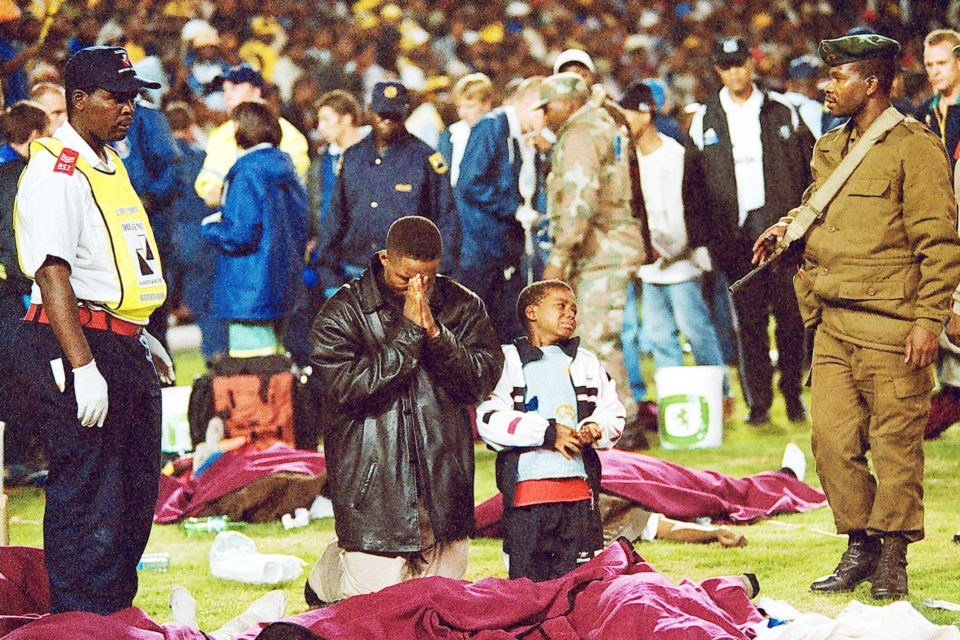

The video footage and images of paramedics trying to revive some of the 158 injured and those already dead laid out under body bags behind the goalposts are burned into the national consciousness.

PSL denial

Annette Nation has become something of a de facto spokesperson for the families. She has been an outspoken critic of the Premier Soccer League’s (PSL) denial when it comes to the events at Ellis Park that night.

Year after year, the PSL’s contribution to memorialising the 43 people who died at their football match has been a terse press statement. They do not attend when the few families who can afford the trip, or who feel up to it, lay anniversary wreaths at Ellis Park. At the time of publication, the league hadn’t yet announced whether or not they would observe a moment of silence at this weekend’s matches.

And every year, Nation’s outspokenness and willingness to speak sees her called by journalists looking for a soundbite for an Ellis Park anniversary story. I ask if she minds recalling that day, when teacher Roy, because it was school holidays, was able to leave early with Rosswin, so excited he’d pulled clothes on over his pyjamas.

“Oh,” she breathes.

Is it too big an ask?

“No, no, it’s not difficult,” Nation says, though there is a definite sense that she’s putting on a brave voice. “I must say, I can easily speak about it now, from where God has brought me from.”

She starts her recollection tentatively, but gathers pace, as if unable to stop.

‘Something happened’

“I think I got home at about 4.30pm. They waited for me before leaving,” Annette says. “It was only half an hour’s drive from where we lived then in Ennerdale. The previous night, when I came from work, Rosswin gave me this looong kiss on my lips. The day of the incident, he just gave me a very quick one.

“He said to his dad, ‘Please, come man Daddy, we are going to be late.’ And you know, I now sit and I think, ‘Late for what? Late for his appointment with the Lord.’ And it was just ‘bye’ and gone with them. My mother-in-law called me from Pretoria. She sounded very social and it was ‘How are you? Where’s Roy?’ And I said, ‘No, Roy’s gone to the stadium.’

“Something happened at the stadium.”

“She said, ‘Oh, I saw something happened at the stadium.’ And if I’m not mistaken, at that point she said to me, ‘I think 17 people have died.’ I just remember that.

“That was on the landline. I took my cellphone and I tried to call Roy, but for some reason I just could not get hold of Roy then. I called my brother, because he lived in the same street. My sister-in-law said my behaviour was just … I wasn’t myself. She has said she felt she could smack me. Because I was so … I wasn’t negative. How can I put it? It was almost like I could feel that something happened. Does that make sense?

“My brother said his car’s parked there and, ‘Come let’s go.’ And I’m running to go fetch my car and he’s like, ‘What do you want to do?’ I’m thinking, ‘Let’s go to the police station.’ He said, ‘What are you going to do there?’ I said, ‘Okay, let’s go to my cousin. Let’s go to Ellen.’”

Another victim

Roy and Rosswin Nation had gone to the match with the husband of Annette’s cousin, Ellen Arnolds. Calvin Arnolds, 34, was another one of the victims.

“On our way there, Roy called me. And I was shaking and shivering, and I said, ‘Roy, are you okay, is Rosswin okay?’ No, no, no… actually, before I could even ask, Roy was just crying and he said, ‘Annette, Annette, Rosswin’s gone.’”

Annette Nation breaks down, sobbing uncontrollably.

“I said, ‘No man, it can’t be. Maybe it’s just his leg that’s broken. His arm. Go check again, Roy! Go check!’

“I don’t remember what I said afterwards. My brother said he took the phone. My uncle went to fetch Roy. I couldn’t sleep. I remember sitting up and all I was telling myself was, ‘I’m going to fetch Rosswin tomorrow morning.’ The next morning, reality hit when we had to go and identify the body.”

Voice cracking, Nation said: “I’m crying like this. It’s been 18 years.”

I apologise to her. I am opening something up again and I feel abhorrent.

“No, no. I have to tell my story,” she says. “If my story can help someone else, if it can help another mother who’s been through it, I’ll gladly tell the story.”

Controversial recommendation

The events of that night have been patched together, largely through testimonies to the Judge Bernard Ngoepe Commission that followed, which recommended controversially that nobody be held criminally liable.

Until the Ellis Park disaster, tickets for football matches in South Africa were available at the stadium on the day. That Wednesday, with Chiefs having won their previous game to re-enter the title race and Pirates leading, a huge crowd turned up late. Many were rushing from work for the 8pm kickoff, walking to the centrally located, 62 000-capacity Ellis Park stadium. Estimates are that 80 000 or more spectators tried to force their way into the stadium.

Tickets were sold out by 7.15pm, but the gates were broken down and fans surged into the already packed stadium. Chiefs scored early, and when there was a roar from the Pirates fans for Benedict Vilakazi’s equaliser, the surge in the crowd increased. Too few security officials, a slow response from the police and no one person being in charge to take control of the situation were the factors the Ngoepe commission found to be responsible for the stampede in which spectators were crushed.

Related article:

The PSL initially paid a paltry R15 000 to each bereaved family for funeral costs, then a further R7 500 from a trust fund. In late 2004, amounts of as little as just over R30 000 to around R100 000 were awarded in a civil claim.

Annette Nation’s recounting of that period hardly makes it sound like part of a healing process.

“No, not at all. Another thing is, at that point I was too broken to even think of fighting for anything,” she says. “When the incident happened, the PSL were there for us and all the promises they made about always being there for us.

“They even arranged counselling. But we would be with this person, counselling us. The next thing, ‘No, we can’t make use of this person,’ and another person would come, only to find out that they never paid the people.

“They drew the case out for almost three years. With us, they argued that Rosswin wasn’t a breadwinner. One of their lawyers said to Ellen, ‘This is not a get-rich-quick [scheme].’ It was basically, ‘You have to fend for yourself.’”

Rosswin’s name

Nation began trying to engage the PSL for greater recognition of the anniversary “about five years ago”.

“I just said to myself, you know what, I would like Rosswin’s name to live on. The Ellis Park disaster is part of our history. If it is that, then let it live on.

“I recommended that the PSL have a moment of silence in at least one Soweto derby a season. They said yes, they would discuss it in their meetings and give us a written response, and they dragged their feet.

“The second year, I approached them again. Eventually, I could see now that they don’t want to have anything to do with it.

“I tried to get them to have an official ceremony at Ellis Park on the anniversary. The PSL first had the memorial for about three years, then they said, ‘No, we’re not going to.’ It’s like they just want to forget about everything that ever happened. But I make it a point to tell them my story.”

Opportunity to grieve

PSL chairperson Irvin Khoza, also the chair of Pirates, was asked this week if the league was planning any significant event to commemorate Ellis Park this year.

“There was a press conference at Ellis Park where we made a commitment to say we thought we must give the families an opportunity to grieve. And that was my last kind of honouring of that event,” Khoza said.

“But if it’s the 20th anniversary or 30th anniversary, there’s nothing stopping the two clubs [from holding a commemoration].

“Obviously, we have got challenges of the Klerksdorp [Orkney] disaster [where 42 fans died in an overfull stadium at a Chiefs-Pirates friendly in 1991], because there is nothing to prioritise one over the other.

“The Ellis Park disaster issue is an emotional one. And we did not abandon it, because we did make a statement that we have done the part. We are asking that the families be given a chance to grieve. But the door was never closed.

“We always recognise it on our website in our small way. But the big one, the 20th anniversary or 30th anniversary, I think it’s only fair to remind ourselves and remind our supporters who all love football. And we will maybe announce that in due course.”

Opening wounds

Annette Nation, when asked why she and other family members who speak to the press – such as Ellen Arnolds and Beauty Maribe, the aunt of Bucs fan Mduduzi Thomo, who died aged 27 – have become unofficial spokespeople when so many of the other families have drifted out of contact, can only speculate that they do not want to open their wounds each year.

But it is difficult to believe they do not want an official ceremony to carry the memories of their loved ones who perished that night, 18 years ago.

Instead, the few who are willing to speak must shoulder that vicious burden.