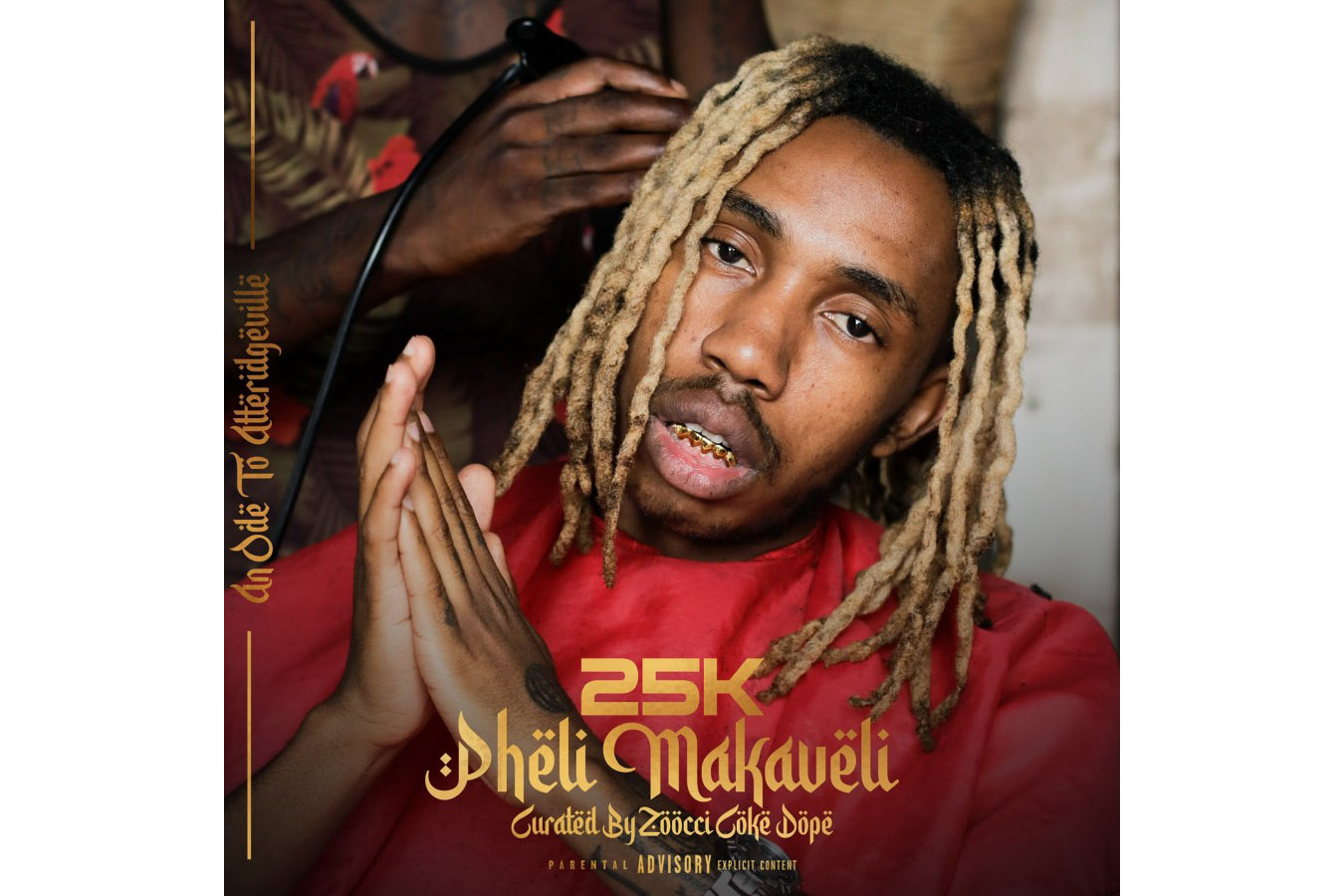

25K’s ‘Pheli Makaveli’ is a kasi trap gem

The rapper’s debut album offers us Atteridgeville’s rhythm and flow while telling the story of hustling as part of a generation of young people that the government has failed.

Author:

3 December 2021

Autobiographical in nature, 25K’s debut album Pheli Makaveli is an indirect political statement. The 27-year-old rapper and producer’s 12-track album, recently nominated for the Album of the Year category at this year’s South African Hip Hop Awards, paints a self-portrait in his Atteridgeville (or Pheli) context. Even though he doesn’t directly call out the government for its failures, his story, which is told in colourful detail with an authoritative delivery, is a mini exposé of its inefficiencies. Pheli Makaveli, when consumed as a whole, tells a story that points to a system that fails its young.

“Me and Zoocci Coke Dope [the album’s producer] fully understand the place that I’m coming from and the challenges that come with it. We used to sit and have these chats [about] how we barely have resources in the hood, in terms of the arts and many other things … [about] the high unemployment rate and high crime rate and how certain people end up in messed up situations because they didn’t necessarily have many options,” 25K says.

The detail in lines such as “If I don’t make it out, Imma sell drugs/ If you can’t load a clip, you ain’t one of us/ I can teach you how to load, just don’t point at us” in From Dusk Till Dawn reveal a young man who has endured a life of limited options. It’s what happens when you grow up in a country that has one of the world’s highest youth unemployment rates. According to Statistics South Africa, youth between “15-24 years and 25-34 years recorded the highest unemployment rates of 64,4% and 42,9% respectively” as of the third quarter of 2021.

Pheli Makaveli zooms in on the faces behind these statistics. 25K’s story, delivered in fluent Sepitori (Pretoria slang), is sincere and, at times, graphic. The listener is treated to his multiple layers, as the rapper navigates success and recounts his old life, which is still a reality for many of his peers.

“The project is about my upbringing, my story, my journey before the music and when I fell in love with the music. It sums up a bit of everything about me from back when I was on the streets hustling. When I used to stand in the corner hoping to make a little cent,” says 25K.

At the end of the title track, a clip Zoocci Coke Dope lifted from a television news report details the township’s high crime rate. Clips of the infamous Maleven, the unapologetic Johannesburg criminal interviewed by the BBC’s Louis Theroux, are also included. When quizzed why he opted for a life of crime in the viral clip, Maleven responded, “I never go to school, so what can I do?” Another part of the interview introduces Trap Jumpin’, a song in which 25K raps, “On PayPal, I was selling dope/ Making beats on Periscope”. After his music took off nationally, 25K shifted his focus from hustling to his art.

But that’s not to say he deserted the streets. In the song Omertà, he reassures listeners with a mafia-style oath. An omertà is a code of silence about criminal activity, which 25K learned about by watching The Godfather and The Sopranos, which depict how the mob operates. “I’ve now made an oath to the homies that even though I’m doing this music thing, I’ll never let them down,” he says. “So, if they hold it down in the hood for me, Imma hold it down for them with this music thing.”

A man of his word, 25K made sure to share his big moment – a debut album, backed by Sony Music Africa, which was among the most anticipated of the year – with one of his early music companions. The song King’s Gambit features rapper Killa-X from Soshanguve. “When I was rapping in high school, we were a duo and we would sell mixtapes for like 20 bucks,” says 25K. “He helped me pioneer my sound in terms of me rapping in vernac and mixing it up with English from time to time. For me to do this thing on a national scale or even an international scale, it’d only be fair to put him on the song.”

Kasi trap

25K’s chosen medium, trap music, originated on the streets of Atlanta. To “trap” means to sell drugs and, in their early projects released in the 2000s, the genre’s pioneers, T.I. and Young Jeezy, detailed their dealings before becoming famous. Now celebrated globally, trap music has birthed different strains that vary from one region to the next.

“Trapping” is now a broad term that refers to many forms of street hustling. Pioneering South African trap artists such as Emtee, Sjava and Saudi (collectively known as the African Trap Movement) have narrated their tales of rags to riches in trap productions. But their stories, like most South African trap rappers, including Flvme, Champagne69, Nasty C, J Molley and The Big Hash, don’t necessarily involve trapping in the classic sense.

Emtee makes an appearance on Pheli Makaveli on the song Self Made and delivers a fitting verse about the pursuit of money: “Hanka tswara zaka batlo nyela (Wait till I get my money, right, then you can’t tell me nothing, right).” 25K says, “I’ve always been a fan of the African Trap Movement. When I first listened to [Emtee], me and my brothers were like, Emtee’s crazy, he’s talking that talk.”

Owing to the US influence on most South African trap music, some critics have labelled the genre’s practitioners “American wannabes”. “The misunderstanding always comes from when people hear the sound and they think, ‘This dude is trying to be like a Rich the Kid or a Young Thug. He is not really trappin’ like that,’” 25K says, before making it clear that he is different.

“Where I come from, people will vouch that I’m an official trapper. I’ve seen people I grew up with get 10-year sentences,” 25K says, “and I’ve seen people die. I’ve really seen the trap life. I’ve seen the more graphic side of the streets. As a small-time hustler, I’ve been around big-time hustlers who’ve taken bigger risks than me. I’ve seen that life in person.”

In the song Project Baby (Interlude), 25K raps, “I stick to the process, I was raised up in the projects”, referring to the housing projects the US government created for the disenfranchised. “In the song, I’m saying I’m a township kid, but in a hip-hop sense,” says 25K.

Fixating on the use of foreign vernacular in this case would be short-sighted as 25K’s subject matter is his township upbringing and lived experience, his take on the popular subgenre “kasi trap”.

The line “It’s a decoy when we protest” in the interlude’s hook refers to when protests are hijacked by people with ill intent. Pheli Makaveli’s 23 July release occurred as the country was picking up the pieces from the riots that swept through parts of KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. But it was nothing new to 25K or anyone who lives in a South African township. “Sometimes people in the hood are not really involved in politics like that, but they face the struggles, so they protest,” he says. Breaking down the line on the album’s liner notes on Apple Music, he speaks about how blockades, burning and looting are aspects of what occurs during protests.

West Coast influences

Fellow Pretoria artist and producer Zoocci Coke Dope, whose credits range from Blaklez to A-Reece and Flvme, curated and produced Pheli Makaveli, which started taking the form of an album spontaneously.

Zoocci Coke Dope contacted 25K in 2019, just as the artist was about to release the music video for his breakout single Culture Vulture, a song that was later treated to a remix featuring AKA and Emtee after 25K signed a deal with Universal Music.

Related article:

During the initial recording sessions, Zoocci Coke Dope picked up the influence of Tupac Shakur and West Coast rap in general on 25K’s raps. “That’s when he came up with the name of the project,” says 25K. “And then all the songs we started recording after that started to make sense in terms of the album’s direction.” As a result, Pheli Makaveli is replete with West Coast rap Easter eggs and overt references from the album title to Tupac interpolations.

Just like Tupac did in the 1990s, 25K tells the story of the streets in the language of the streets. And, similar to Tupac’s music, one does not need to be from the same environment to relate. There is a shared story of struggle in hoods around the globe, with regional nuances. From California to Pheli, people fall victim to the streets, as Tupac rapped on Unconditional Love. On Pheli Makaveli, 25K leaves the theorising to the scholars and focuses on sharing the source material.

Pheli Makaveli is available on all platforms.